This interview originally appeared in the in July 2020 Sport and Geopolitics Program of the Geopolitical Sports Observatory.

THE SEPARATION BETWEEN SPORTS AND POLITICS?

American presidents have often been labeled as “Sport Presidents” (Green and Hartmann 2012), utilising sport to benefit their image and popularity.

IRIS: How can the myth of “sports and politics don’t mix” be explained?

DR HARTMANN: I think it starts from our idealised conception of both sports and politics, idealised in the sense of their stereotypical definitions and commonsense cultural conceptions. On the athletic front, we think of sport generally as a very pure, safe and even positive, unifying kind of space or social force. For some people, it’s not idealised but more just a matter of entertainment or distraction from other things. The biggest idea is that sport is supposed to be somehow special, separate and distinct from everything else in our regular social lives, and that we have to protect that. On the politics side, I think a lot of people, in the United States at least, think of politics as dirty, complicated and inherently contested and conflicted. You can see almost right away that these two don’t go together very well. And, in fact, much of this modern thing we now call sport was built around this distinction, the idea or ideology, the mythology of sport being sacred, progressive and safe from other things, explicitly in contrast to their idea of the dirty complicated politics of the real world; from its inception, the sporting establishment has wanted it to be sanitized or safe from that.

The reason we sometimes call it a myth is that, in reality, sport and politics are deeply, almost inherently and always intertwined. Often, we don’t recognize this because some of what we scholars would say is political isn’t constructed or understood as political by those who are doing the actual talk about sports and politics in society. Some of the best examples would be around nationalism and the use of flags and anthems in ceremonies that celebrate the nation-state in athletic arenas. While many participants just think of this as normal or typical and not particularly controversial (and thus not “political”), from an analytic point of view, this can be seen as a kind of politics, a politics of culture and symbolism used to celebrate and reinforce certain notions of nation and identity. Because so many people agree with the messages, or just take them for granted or even ignore them, it seems harmless or apolitical even though its political content and function are pretty overt when you think about it. And so there, I think, is kind of the root of the challenge—that, on the one hand, sports and politics are always intermingled in many ways that we often can’t see or aren’t aware of, but that we think they shouldn’t be both because of our conception of sport as a special place and politics as a problematic one.IRIS: Can the current president, Donald Trump, be labeled as yet another “Sport President”? How has he utilized sport so far?

DR HARTMANN: Nearly all 20th century American presidents, going back to Teddy Roosevelt’s fascination with muscular Christianity, military might, and American football, might be called “sport presidents”. American presidents have talked about sport, used sport in their political rhetoric, in their public personas. Whether it is Richard Nixon in ping pong diplomacy or Bill Clinton on the golf course, George Bush, Ronald Reagan, every president or almost have ways that they publicize and promote their connections to sport. For Barack Obama, it was basketball. And typically, they do this not only to promote themselves and their agenda, but to reach a broad, bipartisan public audience, trying to unify around and through sports. And that’s a delicate balance, a narrow tight rope—because of the taboos that separate sports and politics, this presidential sports talk and engagement has to be done in ways that don’t seem political but rather just natural or organic, playing into things we can all just agree upon. This brings me to the current occupant of the White House.

Our current president, like those before him, talks a lot about sports. He also plays a lot of golf and has his own history of sport’s involvement, which is actually pretty complicated and controversial. Among other things, he’s tried to get in of the ownership of the National Football League (NFL) many times, even though the league has not allowed that to be the case. What is distinctive is not that sports is part of his presidency, but rather how he uses and engages sport politically.

What I think is particularly different about the way that our current leader is acting as a sport president is that he is far more overt and deliberate about being political and actually doing politics in his engagement, discussion, and involvement with the sport world than any president before him. He has tried not to deemphasize or downplay the politics of sport, but bring it out even further and use sports as a way to appeal to his base, to intensify political polarization and to fuel the conflicts and difficult questions in our society, especially in engaging controversies and debates surrounding racism and athletic activism. What is so important about that, and so different and unprecedented, is that all previous presidents, whether they are republican or democrat, liberal or conservative, have tried not to have sport is politicized when they use it. Even more specifically than that, they have tried to use sport as a unifying force to appeal across bipartisan divide, to appeal to liberals and conservatives, and to all people of all races and religions. For instance, the more conservative presidents, the Bushes, Ronald Reagan, Richard Nixon, as controversial politically conservative as they might be, were trying to appeal to a more unified nation as a whole when using sport. And they were very cautious to avoid appearances of politicization, of division and of polarization. The current president, I think, is taking the exactly opposite tack. One prominent example would be something I’ve been studying and tracking in my own research: the controversy and questions around Colin Kaepernick’s kneeling during the national anthem before NFL football games.Kaepernick started this gesture in 2016 as a way to call attention to police brutality and racism, especially that directed against Black’s men. By the summer and early fall of 2017, however, it did not appear that there was going to be any additional protest on the part of NFL players. They had made the gestures, taken a stand the year before and thought they made their case. With Kaepernick himself getting bullied and driven out of the league, there was not much talk of additional gestures, much less of protests. Why did that change? In a nutshell, because the president decided to make it an issue. He started talking at rallies, with vulgar language, about the evils of athletic protest, threatening anyone that might consider this an acceptable way of protest. This, pretty clearly in my view, was to play to his base, to further polarize positions and try to promote himself as a champion of the conservative wing of his Party and American society. Interestingly and almost predictability, this did give rise to an incredible round of activism, not only in the NFL, but all across the sporting landscape. I am actually quite intrigued and inspired at how athletes across many sports, many levels of sports responded, a response by the way that is continued and accelerated in the current moment. I want to say more about that in a moment. But I also want to be clear, I think in the incredible wave of American athletic activism in the fall of 2017 got energized and accelerated by the deliberate attempt, the deliberate act of the president to polarize and politicize sport.

AN AMERICAN TRADITION OF ATHLETE ACTIVISM?

IRIS: Kneeling down during the national anthem to protest racial inequality and police brutality has been widely decried by a faction of American society who has accused Colin Kaepernick and other athletes of disrespecting the flag, the military and the nation as a whole. Why did the “Take a knee” movement sparked such negative reactions among conservatives? Was it caused by Trump’s response or part of a broader opposition within American society?

DR HARTMANN: The movement of activist athletes right now with Black athletes at the center is bigger, broader and more sustained than any form of activism among athletes that we have ever seen in US sport history, and it goes back further than most people realize. I think it really started to take shape in the late 2000s and early 2010s, around the reaction of the killing of Trayvon Martin and the reactionary, racist backlash against President Barack Obama, our first Black president. Athletes were among many Americans who were deeply troubled by what was happening in society, and even in the very beginning by the conservative and reactionary responses to some very basic injustices that were being brought to the surface. So, we are talking about an almost ten-year-old movement that has involved athletes at every level, across racial and gender lines, and even involving coaches and others. It is nothing like anything we have seen. And the mobilization that has happened in the last month or so in response to George Floyd’s murder here is in Minneapolis and the rise of support for Black Lives Matter is a continuation, expansion, and explosion of that consciousness and awareness.

Now, to get closer to what you are asking about, there has been a backlash and opposition to this athletic activism from the very beginning, and it has come not only from conservative Americans who disagreed in fundamental ways with the actual social views and goals of activists and protestors, but also from those who thought of themselves as more moderate but who didn’t think sport was the place to have these kinds of conversations and debates. What has taken shape in the last decade in activism has challenged the very understandings not only about politics and its relationship to sport but protest and its relationship to sport. And it has particularly challenged not only people on either end of the various political or ideological spectrums, but those who are kind of in the middle and who have wanted to defend sport as a neutral, color-blind, apolitical space. It is coming to the fore right now that in a polarized society, where there are clear debates about what’s right and wrong and what constitutes justice and injustice, to sit in the middle and not take a side and to say that sport should stay outside of that, to claim that it’s neutral and it should not be part of that, is unfortunately on the side of the status quo and of those who are trying to defend things as they are rather than the activists who try to use the platform of sport to speak for the need for social change and social justice.IRIS: Why do you think activism in sport and among athletes is so taboo?

DR HARTMANN: The broad challenges about activism in and through sport are cultural, tying back to the cultural dichotomies and taboos that we started this conversation with, the mythological separations between sport and politics, and the perception of sport as a sacred place immune from conflict and corruption of the regular world. In a certain stance, protest is an even more extreme or amplified version of these dynamics, the inherent tensions between sport and politics in our culture. In other words, the taboos that we have about politics and sport apply to protest and sport because protest is perceived as an even more extreme conflictual societal version of politics. Here, it might be useful to note that in sociology we often define protest and social movements as “politics by other means”, or “weapons of the weak” used by people who lack conventional power and resources and resort to protest to make their voices heard. Therefore, protest in the sport world is also a way of trying to use other means to express societal and political issues.

Secondly, what is really challenging on the protest side is that sport has an additional ideology about itself being a progressive force in the world, especially with respect to race and racism, and movements for racial mobility and change. The sport world has always wanted to believe that it’s a real arena of meritocracy, of fairness, of advancement for minorities and all disempowered peoples; this is one of the founding ideals or beliefs on which the sport world has built its legacy. Good as it might sound, this self-celebrated ideology really makes it hard for athletes who want to speak out about racism either in society or maybe just in the world of sport itself because they are forcing the sport world to call into question the sanctity of one of its own founding myths. The very thought that one needs to protest in or through sport suggests that just playing sport does not necessarily contribute to a broader racial cause and more justice. And in fact, some of what can happen is that their participation – even when successful – actually works back to legitimate social inequality or even to perpetuate some of the worst racial biological stereotypes that we know in the Western world.

Another part of sport culture that makes athletic activism challenging is that for a lot of people – perhaps especially some of the most passionate sport fans – sport shouldn’t be taken as anything other than a form of entertainment, a diversion from everything else. It’s only some of us who have the luxury to think we can get away from that for a while and just watch sport or root for our favorite or play sport while not having to be bothered by questions of racial inequity, sexual injustice, issues of ability or the challenges that religion minorities face. That’s not a privilege that everybody can have. Therefore, when protest in sport occurs, it forces others to acknowledge the complexities of the world that the sport world is actually deeply implicated in.

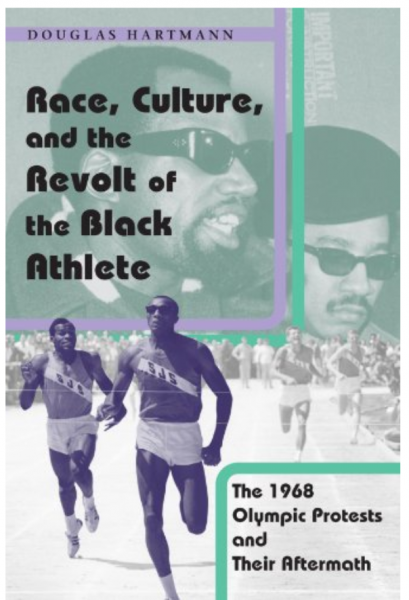

A historical example is the 1968 Black American Olympic protest, when Tommie Smith and John Carlos stood with clenched fists raised above their heads during the most sacred moment, the victory ceremony with the national anthem being played and the flag being raised. I wrote my first book about this (Hartmann 2003). Many people do not fully understand the history behind that gesture. It was not a spontaneous act but rather the product of a year-long effort of activism and mobilization by Tommie Smith, Harry Edwards, Lee Evans and others who had actually called for Black American athletes to boycott the Olympics altogether, trying to use the platform of the Olympics to call attention to the injustices that Black Americans were experiencing in the United States and to contribute to the movement for racial justice that we call civil rights and/or Black Power.

Smith and Carlos were the first of a new and then unprecedented wave of Black activist athletes. In the first half of the 20th century, Black athletes helped to break down the barriers of Jim Crow and segregation of American society just by being athletes. Through the expressions of excellence, brilliance and creativity of Black Americans in the Black community in the face of extreme marginalization and injustice – there were sending messages of progress, justice and change in American society. By the 1960s, Black athletes began to realize that they needed to do more and to contribute to the movement for justice in order to be part of change. This was both because resistance was radicalizing, the times were changing, and more overt actions were needed if progress was to continue, and also because Black athletic success was, by the later 1960s, beginning to get used by conservatives to legitimate, rationalize, and justify the racial status quo by suggesting that if Black athletes could achieve success and win gold medals then this confirmed that racial barriers were falling away, or even that there were no racial problems in the United States.

Realizing this, Tommie Smith, who was actually fairly moderate and indeed had planned to enter into the military, refused to let his body and his performance be used to legitimate a racist regime. Smith didn’t necessarily want to protest but he also refused to be let the media and conservative forces to rationalize and justify a racist society and the lack of necessary social changes. I think many of our athletes, especially those who are the most famous and well paid, are motivated by similar forces and considerations today as well. They refuse to be seen as emblems and symbols of progress and are also committed to call attention to the brutality, the violence, and the injustices that members of their communities and themselves experience on a daily basis.

IRIS: Can we compare recent mobilizations against racial inequality in the domain of sports to other historical episodes of athlete activism, such as the 1968 Olympics Black Power Salute?

DR HARTMANN: I just wrote a whole paper explicitly comparing the 1968 mobilization with the mobilization of today (Hartmann 2019) so I have more to say on this than we have time and space to cover. But anyway, there are some basic parallels that can be drawn, especially in how both movements grew out of activism in society that is beyond sport. Both movements – Black Power in the 1960s and Black Lives Matter today – were very polarizing and political, and the public is either with them or against them. In 1968, some thought that Smith and Carlos’ gesture was wonderful and needed, while others perceived it as inappropriate and anti-American, echoing what some of the opponents to Black Lives Matters activists say today. Both are also a preeminent moment in American sport history – maybe in American history – of athletic mobilization. That’s why I think the comparison is relevant.

However, the last decade of activism has been powerful and unprecedented relative to the 1960s, with a much higher participation of athletes today. In the 1960s, activists were a set of very prominent and well-placed athletes, but it was dozens of them rather than the hundreds and thousands that we have been in recent years here. Another big difference is it really is occurring across sport, racial and gender lines, and across levels of sport participation. Female athletes, such as the Williams sisters, Women National Basketball Association players, and Megan Rapinoe, have been particularly important where they were marginalized in the 1960s. Famous white coaches like Steve Kerr or Greg Popovich have been in support. Also, it is really hard to exaggerate how involved even young people are in today’s movement, in youth sport, high school sport or collegiate sport which has been used as a platform to speak out and to express themselves on social issues, whether it’s in interviews or through taking a knee during anthems. It is amazing to me and unprecedented: in other words, it’s not just LeBron James or Colin Kaepernick, it’s kids at parks, at universities and colleges, women and men and athletes, coaches and administrators as well as athletes. It is an extremely broad base and diffused movement.

What we see today is also more sustained. Back in the 1960s, there was about a year of organizing and the reactions of the athletic establishment and American society to Tommie Smith and John Carlos’ gesture were so negative that it became really difficult for athletes to continue organizing in the way that they wanted. Institutional changes did come out of that, for example in favor of gender equity in sport or athletes’ rights, but the race impacts were limited and mostly symbolic in the world of sport. The movement we are witnessing now has been going on for a decade and has begun to lead to progress and change both inside and outside of sport. One reason why athletes are so powerful and prominent right now in the summer of 2020, is because they’re not responding to one event but have been talking about social injustice and racism, demonstrating and organizing for years now. They know how to use their status as athletes to contribute to broader forms of justice and change. And you see it not only in the struggle against racism and police violence, but also in the struggles for gendered equity, against homophobia or in favor of human rights. What we witness today is the expression of deep-rooted commitments that have been years in the making.What has been happening in the last month or so is, I think, crucial because we are at a moment of pivotal change and potential reformation right now, at least in the United States if not in other parts of the world. There is the emergence of the broader social consensus, way outside the world of sport against the evils of racism and police brutality, and widespread demands not just from the usual activist left, but from mainstream parts of society who had sat on the side lines until. These folks are now taking part in marches and asking legislators and leaders to stand up and do something about the systemic injustices and violence that Black Americans have experienced for so many years. All of a sudden, many people, probably a majority in many communities, find themselves on the side of activist athletes. A lot of people who have been critical of Colin Kaepernick are now admitting he had a point. This is an amazing movement not because ideas about sport and politics and protest and racism are shifting, but because public opinion is changing and now aligning more closely with the message and the struggle for justice that Black athletes and others have been promoting for at least a decade now.

To give you a sense of why I think things are changing in society, but not necessarily in terms of our ideals and taboos about sport, let me go back to public opinion about Smith and Carlos again. In the very early 1970s, a survey conducted by Richard Lapchick – a famous scholar on racial issues and activist in the United States who came to prominence for his anti-apartheid work – asking whether Americans agreed or not with Smith and Carlos’ protest. Not surprisingly, he found very polarized results: Black Americans at least by 2:1 margin tended to support Smith and Carlos; white Americans were exactly the opposite. But what everybody across racial lines agreed upon is more surprising and revealing. Both Blacks and whites, agreed that politics and protest had no place in sport. Black folks just didn’t think that Smith and Carlos’ gesture was political—they saw it as moral, a matter of civil rights, a stand for what was good and right. That gives you a sense of how deep the cultural myths we started with were, and I think in some ways remain.

Now, however, I want to suggest that there has been a shift about what is acceptable and moral in society and what we criticize, marginalize and dismiss as political in sport; it’s not fully formed as yet but what we see is that protests in sport and beyond are not even seen as necessarily political but as the right thing to do and as the change we all need to be part of.

IRIS: Social media and how it plays into today’s protest must also constitute a difference with 1968. Athletes today have been using social media, especially Twitter, as a platform to communicate.

DR HARTMANN: That’s a great point. I think social media allows athletes to have a voice and to amplify their voice in ways through a much more direct, unfiltered and controlled connection to the public. This was not possible in the 1960s, where it really had to be processed and mediated through mainstream media and print press which could misreport or decide not to report their message at all.

But there is another structural difference as well, an institutional one. Black athletes have a foothold and actual power in the sport market today in ways that did not prevail in 1968. Colin Kaepernick, although he is not competing anymore, has been able to be so sustained as an athlete thanks to his relationship with Nike, and the ways in which these industries now rely so heavily on Black celebrities but also on audiences that are supportive of Colin Kaepernick and other celebrity athletes like him. Capitalism isn’t blind nor neutral; it goes where the money is, and as public opinion and buying power has been shifting in favor of activist athletes in the last decade. As a result, the industry has given a platform and a literal source of support for athletes. In the 1960s, a lot of these companies would have been on the other side of things. Thus, in addition to the technology aspect, the corporate capitalist industry of sport and sporting brand also represents key historical differences of the current moment.

INSTITUTIONS’ RESPONSES TO ATHLETE ACTIVISM

On June 5, NFL commissioner Roger Goodell issued a statement admitting the NFL was “wrong” in its handling of its players’ participation in the “Take a knee” protest movement and declared that his institution believes in Black Lives Matter – he did so without mentioning Colin Kaepernick. The NFL, as well as International Federation of Association Football (FIFA) and US Soccer, have recently reconsidered their stance of athletes’ right to protest.

IRIS: Why do these sport institutions seem to have become more accepting towards activism today?

DR HARTMANN: First I should say that I think they have not only become more accepting, but they are participating or trying to participate or jump onto the bandwagon. Or at least that’s what they want the public to think. For the NFL, for example, just a few months ago it was incomprehensible not only to allow protest but to support them and even to encourage support of Black Lives Matter. I do not think these athletic leagues and leaders have suddenly had a change of heart about their politics or their role in society; rather, they are acting under the public pressure and public opinion. By allowing protest, they try to see it not as something political but as what the majority of people want.

In the last few years, organisations of the athletic establishment both in the United States and around the world have had different positions. In the United States, which I know best, the NFL has been very conservative and cautious, even negative about athlete activism whereas the NBA has had a much more assertive liberal approach. There’s a number of reasons for that, one of them is because the union in the NBA is stronger, with top athletes in the NBA being more likely to be supportive of activism and to be African American themselves. The league has just responded to that, not only in allowing athletes to speak out but also addressing racism and discrimination within their own ranks, getting rid of owners who were well-known racists, for example.

Moving forward on this, it will be interesting to see not only what kinds of statements and protests sport organisations allow but internal reforms and transformations that the sport world will make to adjust and address its own racism, discrimination and prejudices. I think we are at a turning point in terms of social change. I was astounded at how quickly European football leagues responded and supported Black Lives Matter. To me, all of this activism and support for activism and social commentary through sports is evidence of how quickly shifts are coming in society and the sporting establishment has had to fundamentally rethought its own position. Again, part of the challenges faced by these sport organisations in weeks and months moving forward is not just about their own ideals but about capitalism and consumerism. I don’t want to be too cynical, but I really do think a lot of the sport organisations are pushed into more accepting, if not even embracing positions, because that’s where the public is at. And the public in the US and around the world is who buys the products and who consumes the media, hence they want to be on the right side not so much because they are racially progressive but because their job is to find a bigger audience so they can make as much money as they can.IRIS: This reminded of the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR), whose stance on the Confederate flag really surprised me; on June 10, it announced that it would ban the Confederate flag from its events and properties. Do you think this particular organisation follows the logic you just mentioned? I thought this new rule could be detrimental to them and their viewership, which I assume is mostly conservative.

DR HARTMANN: In the United States, NASCAR is a prime example of all of this, exhibit A because it has been very conservative in terms of its orientation socially and politically. It is one of our president’s favorite sports and it also has the most conservative white audience of any major American sports; it’s deeply implicated and connected to Southern history and to the racism of the South. So yes, the stand that they have now taken is incredible. And to return to my earlier, skeptical point, I suspect it is driven less by huge moral change of heart and far more by public opinion and the demands of the market. Again, maybe I’m a little too cynical about that, but that was astounding to me how quickly they responded, and I do not believe that was strictly a moral awakening.

In terms of organisations in the global sporting establishment, I think the spotlight will really be on the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in the near future because they promote themselves as a moral paragon in the contemporary world, having built their legacy on their claims on contributions to racial justice and human rights – even when they didn’t. When apartheid started to break down with the possibility for South Africa to emerge as a new nation, the IOC and the Olympic movement played a big role in helping to bring Frederik Willem de Klerk and Nelson Mandela together. However, earlier in the 1960s, the IOC was in many ways on the wrong side of apartheid. Now, it wants to see itself as having helped to bring down apartheid and to show that they have been on the progressive side of world history, standing against discrimination and in favor of justice. This is their legacy, and something they need to perpetuate and build upon.

However, the IOC also has, probably more than any other sport institution in the world, a commitment to rituals and ceremonies that they believe are sacred. And these ceremonies and the cultural ideals behind them do not allow for expressions against the social injustices and other commitments that athletes have. There is no place for race in Olympic symbolism, and a very little or negative place for gender. Athletes who care about gender equality or racial justice can hardly share their message during the ceremony, which only wants to celebrate them individually or as a representation of their nation. This is why the IOC has even a more complicated relationship to kneeling and other modes of expression, because they worry – and probably rightly so – that the symbols, ceremonies and rituals that are so much a part of their sacred traditions and myths will get challenged and maybe even radically transformed in ways that they can’t control. That was really clear to them back in 1968 when some of the most upset people about the Olympic movement were not upset with Tommie Smith and John Carlos’ politics but rather worried about the sacredness of the ceremonies and of global sport.I think that the IOC is at this pinnacle place where the contradictions of sport, social change, protest and politics that we started with are just isolated and exaggerated. We don’t quite know where the IOC is going to be on this and just as they were when Covid-19, they will take a long time to figure it out and I am not sure they will get it right.

Works Cited

Hartmann, D. (2003). Race, Culture, and the Revolt of the Black Athlete: The 1968 Olympic Protests and their Aftermath. The University of Chicago Press.

Hartmann, D. (2019) “The Olympic ‘Revolt’ of 1968 and its Lessons for Contemporary African American Athletic Activism.” European Journal of American Studies (14-1), https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/14335.

Comments