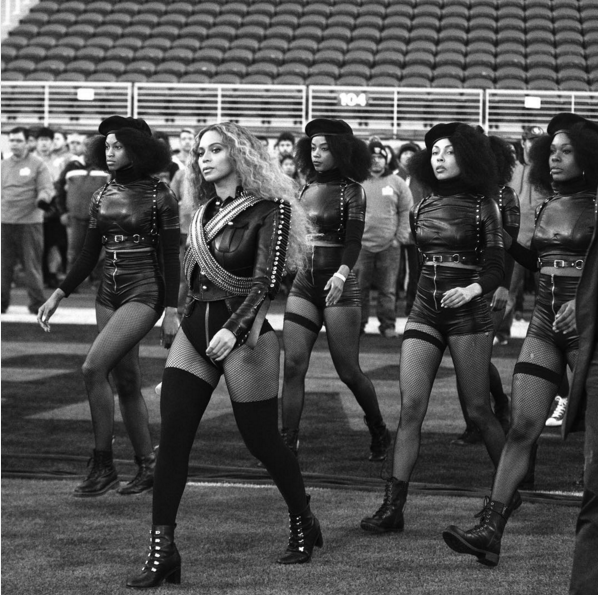

Okay, I’ll make this quick since it’s a bit dated. After I wrote that little post about Saturday Night Live’s “Beyonce is Black” spoof a couple of weeks back, I had a number of students and friends wanting to know what I actually thought about her Superbowl performance (well, her part in the Coldplay performance featuring Beyonce and Bruno Mars). I’m no music critic (or big Beyonce fan, for that matter) so I hadn’t really taken the bait. However, I did spend some time reading what other people were saying—both about the performance and about the backlash it seems Beyonce experienced.

One piece that really caught my attention was by the Salon blogger Lasha. She was struck by the very different reception that Beyonce experienced than the one that met rapper Kendrick Lamar after his racially pointed and politically charged performance at the Grammys just days later. According to Lasha, it was one more instance of the unfair, sexist policing of African American women’s political expression.

Lasha’s point about the marginalization of black women’s radicalism is well-taken. I also think there is some additional social context worth considering. For one, there are expectations and previous record. I think part of the thing with Beyonce is that her Superbowl performance was perhaps her first “socially conscious art.” This surprised folks—it defied their expectations of the “Single Ladies” singer, upsetting those who didn’t see it coming or didn’t understand where she was coming from (witness my previous post on the SNL spoof).

Even more important, in my view, is the actual social context of the performances: the music industry versus the sportsworld. We Americans have come to expect and accept social consciousness and political radicalism in the music context. We not only do not expect such expression in sports, we actually oppose it. Not all cultural arenas are unique, and there are many things about the world of sport that make it uniquely powerful and complicated. As I written on many occasions—for example, in the piece Kyle Green and I did on this site about politics and sport being strange bedfellows—there are deep cultural norms about sport that make any kind of social statement in the realm of sport extremely complicated and typically controversial, especially where race is involved.

I won’t try to rehearse all of the ways this works, much less how racial movements and politics are implicated (there’s a lot on this in my book on the 1968 African American Olympic protests, if you are interested). But when it comes to statements of protest, unrest, and activism, Americans tend to see sport as somehow unique or special—either because we see sport as somehow sacred or sacrosanct (that is, above politics) or because don’t want our entertainment complicated or sullied by the realities of the non-sport world. So while sexism is clearly at play, there’s at least one other important thing going on—the idealization of sport on its highest, most holy day in America: Super Bowl Sunday.

Comments