In graduate school at UCSD, I had a friend in biology (his name was Tom Langen–what’s up, Tom?, if you’re out there) with whom I shared a number of great conversations about the social nature of animals and birds and their implications (or not) for the analysis of human activity. I don’t remember many of the specifics of those conversations, but I do remember that one involving the famed E.O. Wilson ended with my buddy Tom saying, “Well, he did some great ant work.” That’s right: ant work.

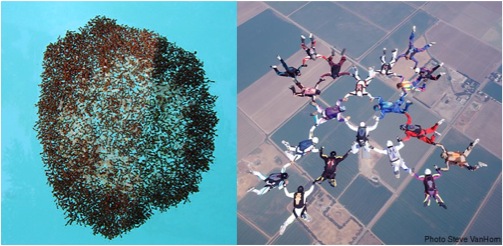

I’m still generally not a big social biology guy, but I couldn’t help but think of Tom and be a bit more sympathetic to the whole Wilson crowd when I read a story in this weekend’s LA Times about how fire ants save themselves when threatened with drowning. Acting together is the key. On their own, individual ants apparently sink or drown in water—or, as they article puts it, they “flounder.” But what most do when so threatened is link themselves together into a floating life raft. The secret, according to researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology writing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, has something to do with the air pockets that are formed when the little creatures fasten their claws onto each other and allow the whole group to float to safety. I guess it’s “Sink or… clamp on!”

The researchers believe these findings could provide a useful model for building complex, cooperative robots. I, however, was thinking about more basic sociological lessons and implications. For one thing, there is the obvious point about the power of the collective: on their own, ants drown; together, they survive. (Just last week I was reminding my 60 graduating seniors that the success of the human species has less to do with our individual brain power or physical strength and far more to do with our ability to work together.)

Which brings me to another, broader set of implications about knowledge and rationality—the intelligence of the collective, the group, in this case the life raft itself. These points are nicely captured in the quote from a Princeton biologist named Iain Couzin the LA Times uses to conclude the article: “The individuals acting together create this awareness of the environment that no individual ant has, and that’s what I think we find fascinating.” How true–and how fundamentally sociological. A group or collective develops into a complex system that can achieve things that no individual member could have imagined or enacted. And while the fire ants don’t have the collective ability to reflect upon and synthesize this “knowledge,” they don’t drown. For our part, we can recognize that, beyond our ability to work together, self-conscious reflection is one of humans’ real sources of power and adaptability in the natural world. The complex social systems we make ourselves into can also be the source of tremendous blindness, inefficiency, conflict, and injustice as well, but I think that’s a story to save for another day.

Comments 1

Altruism, Ants, and E.O. Wilson » The Editors' Desk — March 21, 2012

[...] intelligence of fire ants put me in mind of the Harvard sociobiologist E.O. Wilson (“Fire Ants for Sociology”). I first heard about Wilson in high school (his paradigm-shifting book came out in 1979; I [...]