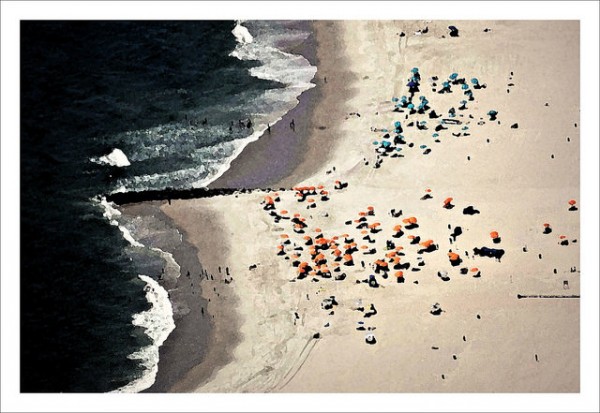

Gentrification is a hot-button issue. The renovation and rebuilding of homes and businesses provide cultural changes that socially separate wealthy whites who move into minority neighborhoods from current residents, even when the spacial distance between the groups is small or non-existent. Looking at the history of residential segregation, Angelina Grigoryeva and Martin Reuf investigate whether whites living in close proximity to racial minorities will result in social interaction or if today’s experiences of segregation will be different than in the past.

The authors use household data from the 1880 U.S. Census to analyze different ways residential segregation appeared in post-Civil War United States. They begin by focusing on Washington, D.C., using data collected by “census enumerators”—people who went door-to-door conducting the Census. Then they examine a larger sample of 171 post-Civil War cities and towns. Grigoryeva and Reuf find regional differences in segregation, noting that the Northeast became characterized by black and white people living in separate districts, while segregation in the South grew to be characterized by a “backyard” pattern, where black and white people live within the same Census districts.

Grigoryeva and Reuf believe their method of tracing residential housing segregation changes the way we think of the history of residential segregation in the U.S., and their findings about the different patterns of contemporary Northern and Southern segregation demonstrate how the social effects of segregation remain powerful, even when racial groups live in close proximity.