Films like An Inconvenient Truth, Super Size Me, and Blackfish can heighten attention to issues by disseminating important facts to a wide audience in ways that books and other media often cannot. But can they actually help social movements achieve change?

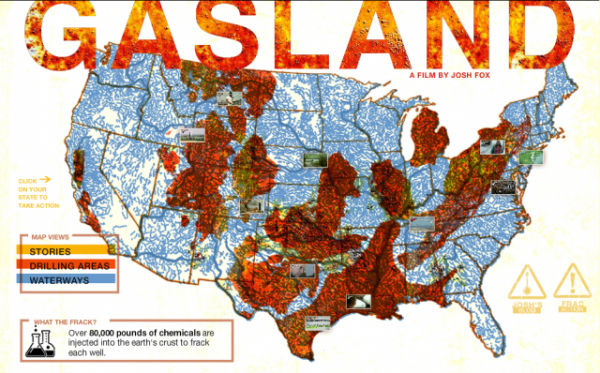

A new study in the American Sociological Review takes up this question by evaluating shifts in public opinion about fracking in response to Gasland, a documentary about the mining practice’s negative effects on nearby communities. The authors evaluate the film’s initial effects in a given community by measuring how the number of Google searches and Tweets about fracking changed after a showing and assessing whether Tweets about fracking were more likely to be negative in tone after a showing than before. They investigate screenings’ longer term effects by charting whether increased web searches and Twitter chatter amplified the likelihood that an anti-fracking demonstration would take place or a ban on fracking would be adopted nearby. They also explore the film’s national effects by evaluating web searches and Twitter chatter after the film was covered in mainstream national newspapers or nominated for awards.

Results suggest that Gasland did, indeed, increase public discussion about fracking, help sway public opinion, and spur mobilizations around the subject. After showings, discussion about fracking comprised more of both social media discourse (as measured by Twitter posts) and mass media discourse (as measured by newspaper articles) than otherwise. The tone of Tweets was also more negative, containing significantly more words like “contamination,” “pollution,” and “chemicals,” “ban,” and “moratorium.” Showings also increased the likelihood of anti-fracking demonstrations and the enactment of fracking bans in communities where the film was screened.

The findings shed light on how movements work in the age of social media. While the effects of screenings upon Twitter chatter were largest in the days immediately following the showing, the increase was usually noticeable as much as four months later. In addition, the communities which had the most Twitter activity were also the most likely to host demonstrations, suggesting that activists were able to capitalize on Twitter’s potential as an organizing tool.

In other words, documentary films and social media have a role to play in changing public opinion and enhancing social movements by helping activists disseminate and act upon information.