Is that? Oh my god. The Statue of Liberty, I said in my head, the words hanging in the whirring jet cabin on its descent to LaGuardia. The figure was so small, its features imperceptible and shrouded in shadow – a dark monolith amidst the gently churning Atlantic. The sudden apprehension of our altitude came with a pang of vertigo.

The plane yawed and a second shape swam into my oval window. Is that… the Statue of Liberty? The original figure and its twin were, in fact, a pair of buoys in the bay. I leaned back in my seat and snickered to myself.

It goes without saying that in this instance my sense of scale, perspective and distance, let alone rudimentary geography, were fundamentally (if comically) off.

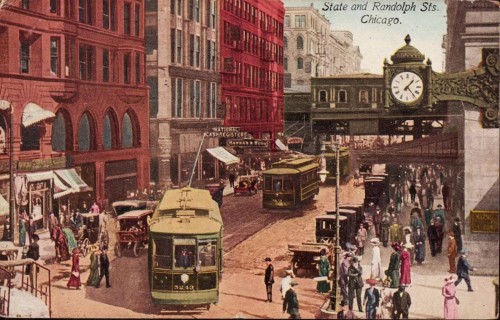

Finding one’s way in an unfamiliar city for the first time always involves an initial phase of bewilderment: the more familiar one is with their home terrain, the more alien the new place appears. Indeed, across my handful of excursions in and around Queens while attending #TtW16, this distortion pervaded my perception of space. more...