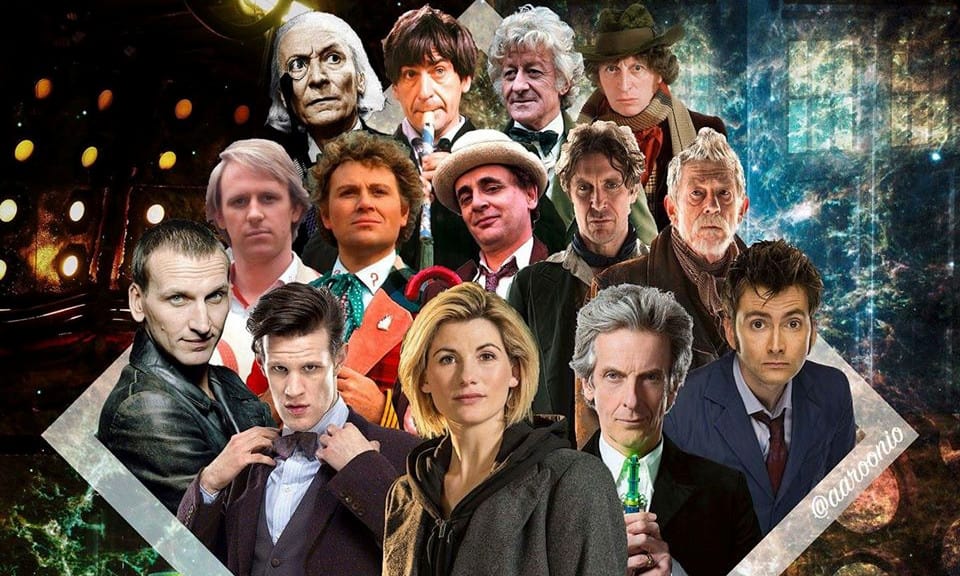

The following argument is as an elaboration upon and the second part of “The Ineluctable Politics of Doctor Who: Part 1.” In that piece, I present the television series Doctor Who as an artefact with ineluctable social-material significance and political implications. In so doing, I illustrate that the ostensibly playful, inconsequential spaces that celebrate beloved objects of fan entertainment never actually enact neutral positions. The text and fan pronouncements about the text exist, incontrovertibly, as partisan acts—even when enacting an ostensibly innocuous posture that seeks to avoid or negate polemical effects.

Here, in Part 2, I address the ways in which the show may and should take responsibility for its social-material effects—which, while demonstrating relevance for a general viewing audience, hold particular import for a diverse fan community. It is on this point of fan diversity that the present discussion locates sociological significance. Surely Doctor Who fans, as a group, constitute a wide range of varying demographic orientations. Such a pronouncement seems rather evident considering the fanbase spans cross-cultural contexts. more...