On February 26, 2012 Trayvon Martin, a Black, 17 a year old, unarmed, high school student, was shot and killed by George Zimmerman, a White Hispanic man acting in the self-appointed position of neighborhood watch captain (click here for more details).

The case has become a symbolic battle ground for two important issues: gun laws and racism. Although both of these issues are inextricably entwined, for purposes of simplicity, I will focus here only on the issue of race.

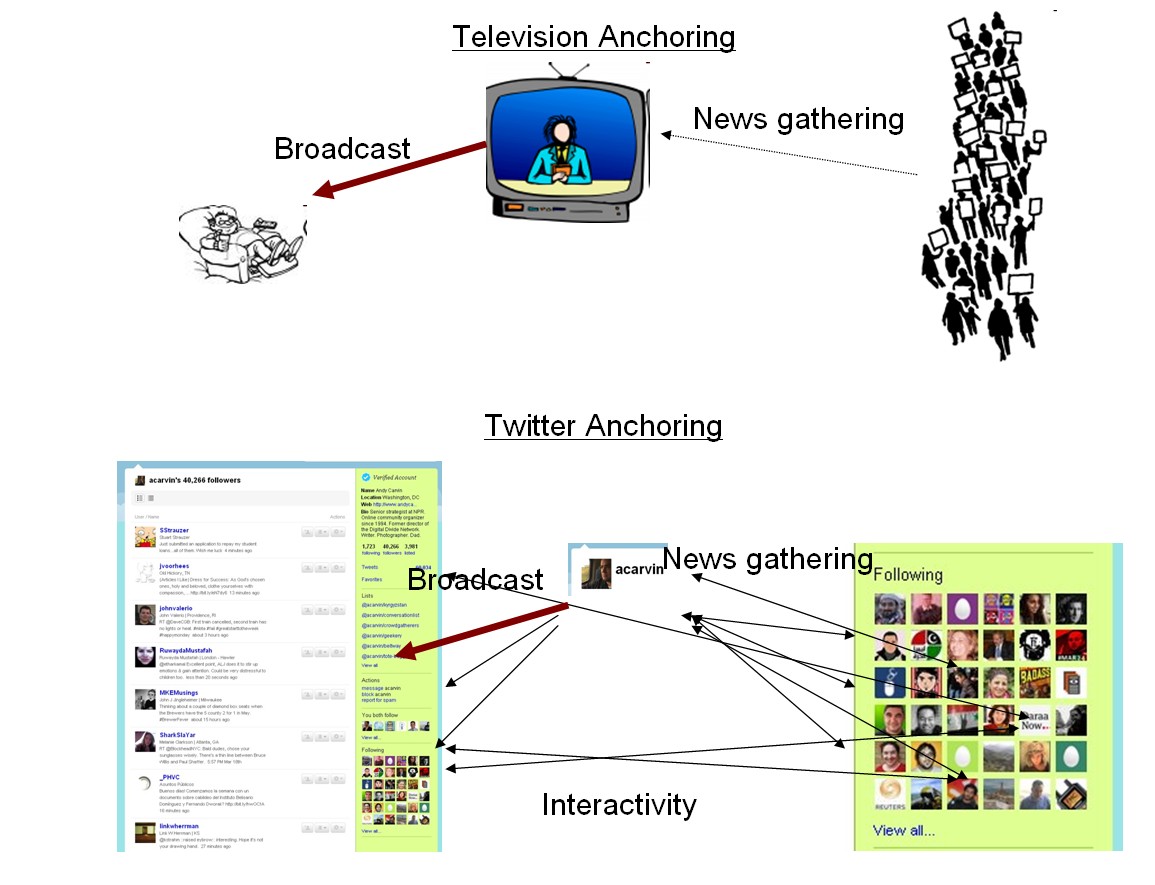

As Jessie Daniels importantly points out on Racism Review, battles over racism have shifted into the realm of social media, where digital and physical race relations persist in an augmented relationship. We see this in both the progressive anti-racist discourses, and the racial smear campaigns surrounding the Martin/Zimmerman case.

Although it is important to expose the overtly racist tactics utilized by some of Zimmerman’s defenders—of which there are plenty—I want to talk here about a more subtle, and so perhaps more problematic form of racial discourse. Specifically, I will talk about how a prominent strategy of protest—coming out of the liberal left—may inadvertently perpetuate, rather than challenge, racial hierarchies in their most dehumanizing form. more...