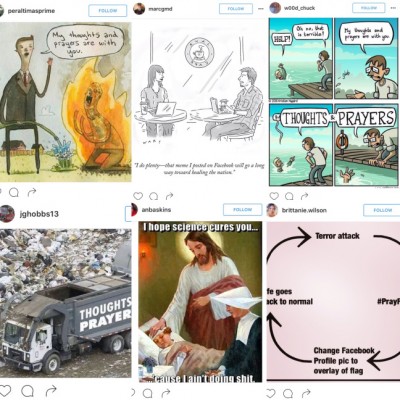

A few years ago, being immersed in my doctoral research about Instagram images and the Manchester Arena attack, I was perhaps too aware of the kinds of images users shared on social media in the aftermath of a crisis. The national flags, the cityscapes and of course the ever-present stylised hearts with the relevant city superimposed, usually accompanied by a #PrayForX. Dutifully, I waded through my dataset each day, assigning categories and themes to these images, identifying patterns.

Enter Friday, 15 March, 2019. I hear the news that 51 people have been killed in my home country, New Zealand. It’s the first act of terrorism the country has ever witnessed. 18,000 kilometres away in Sweden, I’m struggling to piece together this distant and yet extremely close picture. The fragmented scene emerges: two mosques in Christchurch, one of our biggest cities, a white supremacist opens fire on worshippers while claiming to rid the country of “intruders”.

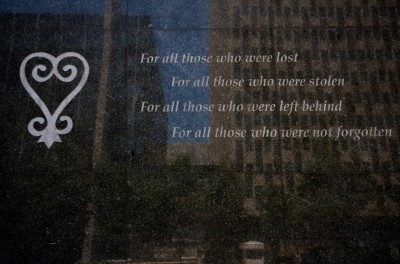

Halfway around the world in another time zone, I cling to scraps of information. All I can think to do is reach for my phone. My cousin sends me a message on Instagram with one word: “awful”. Looking at my feed, I’m instantly confused. It’s flooded with stylised images of New Zealand flags, and what seems like an endless stream of pink hearts, all proclaiming #PrayForNZ and ‘Christchurch’. The images are so familiar to me, eerily identical to those shared after the Manchester attack, almost two years earlier. more...