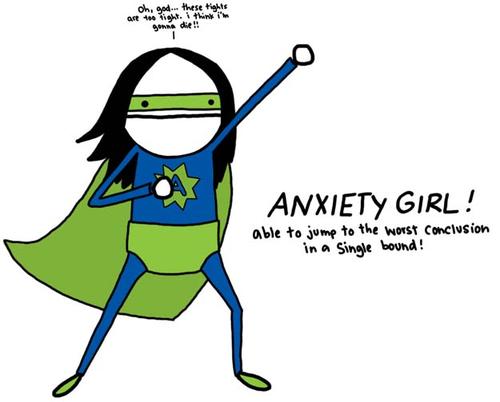

Several weeks ago, I wrote about the “fear of being missed (FOBM).” The flip side of FOMO (fear of missing out), FOBM captures the anxiety surrounding a complex and fast moving online realm in which it is easy to be buried, ignored, and/or forgotten. This anxiety is amplified by the online/offline connectedness, through which invisibility online can lead to neglect offline (personally and professionally). FOMO and FOBM speak to the difficulty of deleting social media accounts, the discomfort of a dead cell/laptop/tablet battery, and the drive to livetweet, status update, tag oneself in pictures, and be physically present for tagable photo-ops.

Soon after posting my piece on Cyborgology, I read Tiana Bucher’s article in New Media & Society about Facebook algorithms and the fear of invisibility. Bucher’s work offers a useful theoretical frame (Foucault’s Panoptican) for FOBM, and an equally good (if not better) term for the phenomena (fear of invisibility). In what follows, I describe Bucher’s piece and its utilization. I then offer critiques of her work. In this way, I hope to further the theoretical substance of FOBM, framing it with the tools suggested by Bucher, and refining it through juxtaposition to Bucher’s arguments. more...

Malcolm Harris has posted

Malcolm Harris has posted

To the questions posed in the title of the panel “Whose Knowledge? Whose Web?”, the answer has too often, and too simplistically, been “everyone’s.” Among Web 2.0’s most strident enthusiasts, the rise of user-generated content is heralded as the reclaiming of knowledge production from entrenched institutions, allowing a brave new world of pluralist democracy to find expression online. These digital evangelists speak of the emancipatory promise of the Internet in language usually reserved for that of markets. In both cases, the prescription is the same: progress is a matter of access. Hence, the “digital divide” has become a discussion about disparities in connectivity rather than one about the expressions and reproductions of social inequalities online.

To the questions posed in the title of the panel “Whose Knowledge? Whose Web?”, the answer has too often, and too simplistically, been “everyone’s.” Among Web 2.0’s most strident enthusiasts, the rise of user-generated content is heralded as the reclaiming of knowledge production from entrenched institutions, allowing a brave new world of pluralist democracy to find expression online. These digital evangelists speak of the emancipatory promise of the Internet in language usually reserved for that of markets. In both cases, the prescription is the same: progress is a matter of access. Hence, the “digital divide” has become a discussion about disparities in connectivity rather than one about the expressions and reproductions of social inequalities online.