In a recent post titled “Digital Dualism of the Real,” Nathan Jurgenson (@nathanjurgenson) wonders if there are several kinds of digital dualisms and, if so, how we should label them. I am a bit surprised by such a concern as I don’t consider digital dualism theory to be divisible or “splitable,” given that I started to develop it in my own way in France. I have found Nathan’s theory of digital dualism very useful; however, because this new idea of different kinds of digital dualisms appears to me as an unwanted consequence of the recent debate with Nicholas Carr, I would like in this post to help him further develop his theory and make it even stronger. That’s why I will start my reflection here by coming back to Carr’s arguments, in order to deconstruct them in greater detail. Because, unfortunately, I think they all are false.

In a post published on his blog only two days before the Theorizing the Web conference, Nicholas Carr is trying to invalidate the digital dualism critiques coming from the Cyborgology’s blog authors. We can wonder why a Pulitzer Prize nominee author of influential books translated into more than 20 languages is so interested in the digital dualism theory. It is easy to answer that: Carr is clever enough to detect that a new generation of digital scholars is developing very strong ideas. And, because he is targeted by them as a digital dualist, he is compelled to attempt to demonstrate the contrary. But he is wasting his time. What are the main objections of Carr?

Carr’s first objection

The observation that “our reality is both technological and organic, both digital and physical” is banal. I can’t imagine anyone on the planet disagreeing with it. […] Nor can I imagine that anyone actually believes that the offline and the online exist in immaculate isolation from each other, separated, like Earth and Narnia, by some sort of wardrobe-portal.

Mr Carr, it is easy to explain why you cannot imagine it: You refuse to admit that many people do believe such a thing, including yourself. It is absolutely not banal to observe that our reality is both digital and physical, once you consider the reality as made of one unique substance. There is a major difference between conscious, logical judgements and value judgements influenced by the unconscious. Using a logical judgement, everybody can describe reality as made of different aspects, such as digital and physical or whatever, as you do in this quote. But what really creates problems in this debate is that, although everybody is able to logically describe (from the consciousness) the enmeshment of the digital and the material, everybody still fantastically believes (from the unconscious) that the digital and the physical are “separated worlds” or spheres. That’s why, in my #TtW13 presentation, I argued on that digital dualism is mostly a phenomenological issue based on a metaphysical fantasy (more than a fallacy, even if a fantasy is obviously a fallacy).

My point is that there does exist nowadays, in dominant mentalities, a fantasy of the difference between the virtual and the real. It can be described as an ontological value judgement coming from the unconscious and shared by many people, according to which the digital and the physical, the online and the offline, are separated realities or worlds. That’s why Nathan is perfectly right when he states that digital dualism is “the belief that online and offline are largely distinct and independent realities” (the word “belief” is much better than the word “bias” or “tendency”). The Cyborgologists do not simply describe digital dualism as a logical judgement, so please don’t behave as if you had not understood. In my interpretation, they are talking about digital dualism as a psychological fantasy that relies on an ontological value judgement, which is mostly rooted in belief. And, Belief is not Reason.

(I tried to explain where this belief comes from in my presentation when I talked about the “phenomenological violence” of digital revolution. You’ll find more about it in my forthcoming book, Being and Screen: How Technology affects the Way we Perceive [to be published in French in next September]).

Carr’s second objection

We’ve now entered a realm of very fuzzy semantic distinctions. What the terms “worlds” and “reality” actually denote is not at all clear.

Sure! I could not agree more. But, Mr. Carr, cannot you see that those fuzzy distinctions are not scholarly distinctions offered by researchers (Cyborgologists or others); rather, they are popular distinctions coming from the everyday ontology of regular folks? No serious philosopher would admit such a stupid divide between the Real and the Virtual. It is completely opposed to the Western philosophical tradition–from Aristotle to Deleuze–according to which the Virtual is a kind of Real, and not the contrary of the Real. (If you are not familiar with this philosophical tradition, I recommend the (1995) book by French philosopher Pierre Lévy : Becoming Virtual: Reality in the Digital Age).

Ontology is not only an academic affair. Everybody does ontology in their everyday lives, because everybody needs a representation of the world in order to live within it. However, because most of people are not professional ontologists, they have built a popular ontology in order to try understand what’s happening to them into the digital era. This is the origin of the deceptive divide between the Real and the Virtual. That’s why those terms “world” and “reality” seem to you so unclear. Because they are not well-reason concepts; they are fantasies or beliefs from popular ontology.

On the contrary, “digital dualism” is a proper philosophical concept. “Virtual,” “World,” “Reality” are each deceptive names for the same fantasy: the (neo-Platonic) belief in a place that is separate and distinct from our physical place. The concept of digital dualism confronts this fantasy with philosophical reasoning. There is no difference between the real and the virtual, there are no separated worlds, there are no worlds. There is only one reality, one single continuous substance, which is the fundamental principle of what I call now digital monism. And, it is absolutely not banal to promote awareness of this, because most of people have so great desire to believe in digital dualism.

People really do feel a difference and even a conflict between their online experience and their offline experience. They’re not just engaged in posing or fetishization or valorization or some kind of contrived identity game. They’re not faking it. They’re expressing something important about themselves and their lives—something real.

Don’t deny it, Mr. Carr: There does exist a “general and delusional dualist mentality.” That’s obvious. That’s exactly why, as you say, “people really do feel a difference and even a conflict between their online experience and their offline experience.” Yes, I really do feel myself this difference in my own life, but I absolutely don’t feel this difference as a conflict or a problem. And, I think that our kids will be less and less likely to feel this difference as a problem or a conflict. It does not mean that they will stop feeling the difference. The difference will always be perceptible. One century after the invention of the telephone, we still know the difference between the face-to-face presence and the telephonical presence. But we don’t feel it as a problem or a conflict anymore. We know how to enmesh them peacefully. That’s the same with the difference between the digital and the physical: We are learning how to enmesh them peacefully and, very soon, we will no longer feel them as a conflict.

Carr’s third objection

Nature existed before technology gave us the idea of nature. Wilderness existed before society gave us the idea of wilderness. Offline existed before online gave us the idea of offline.

This is a very famous Rousseauian naive illusion. Since Homo habilis started to use stones as tools, more than 2 million years ago, Nature has never existed. Any serious philosopher knows that. I can remember what Prof. Jean-Claude Beaune, my old professor of philosophy of technology in Lyon, wrote in 1972 (!):

The world we are facing, in our most daily experience, is cultural, that is to say technical and technicized in all parts. We have no natural experience of the world and of ourselves. (1)

We never lived in a “state of nature” because Nature has never existed for us, as Humans. Our human world has always been “technologically textured” (2), more or less (and today, more than less). Of course, mountains and rocks are real. But, please, do we live in mountains? Only with technical stuff. Otherwise, we don’t live there. The human lifeworld has always been a techno-Nature.

So, Mr Carr, you have a logical fallacy on your hands: “Nature = Wilderness = Offline.” It is completely wrong. Nature and Offline encompass the presence of humans (and have always technical aspects) whereas wilderness is based on the absence of humans (which therefore excludes any technical aspects). So you cannot refer to the Wilderness in order to give sense to the Offline. Not comparable.

(Nathan also responded very well to this objection by arguing on that “Nature is always a social construction.”)

Carr’s fourth objection

“A mode of human experience is being lost.”

This is absolutely invalid. Techniques always accumulate. Modes of experiences conditioned by techniques are never lost, but just add up, enhancing the possibilities of human experience. More than one century ago, we invented the telephone and it affected our lives as much as digital media do now. This is what Herbert N. Casson said in his early (1910) The History of the Telephone:

What we might call the telephonization of city life, for lack of a simpler word, has remarkably altered our manner of living from what it was in the days of Abraham Lincoln. It has enabled us to be more social and cooperative. It has literally abolished the isolation of separate families, and has made us members of one great family. It has become so truly an organ of the social body that by telephone we now enter into contracts, give evidence, try lawsuits, make speeches, propose marriage, confer degrees, appeal to voters, and do almost everything else that is a matter of speech.

We could say exactly the same today about the digitalization of life. We had not lost the face-to-face mode of human experience because of the telephone. We added it up to our experience possibilities. And we’re doing the same today with the Internet. That’s why I agree with Carr when he admits that, actually, he is afraid :

“We sense a threat in the hegemony of the online because there’s something in the offline that we’re not eager to sacrifice.”

Thank you for admitting it, Mr Carr. You’re afraid by new technology. And that’s because you believe in the logic of substitution of technologies instead of the logic of accumulation.

Why spliting digital dualism theory?

Let’s now go back to Nathan’s post on “Digital Dualism of the Real.” It seems to me that this is an overreaction to Carr’s comments, perhaps because Carr is a famous columnist and writer in the United States (whereas he is known as an alarmist thinker in France)? Nathan says:

Nick Carr, as much as we disagree, has always been right that the terms being used here are less than clear.

As I just explained above, those terms are not academic terms. They are people’s terms, coming from the popular dualist ontology. If those terms are not clear, it is because the popular dualist ontology is not clear. And it is not clear because, of course, it is wrong! That’s exactly why the digital dualism theory is true. So, when Carr said this, he was just giving another proof in favor of digital dualism critique.

Anyway, Nathan says he would like to switch gears. So he reminds us the classic philosophical distinction between the real (what includes existence) and the true (what holds authenticity). He correctly points out that we often use the term “real” to capture both meanings. But he explains that, on the one hand, if you focus on the real as what includes existence, you’re led to an ontological digital dualism critique, only concerned with objective realities, i.e. isolated from subjective concerns of people and of what people think is important/human/deep. On the other hand, if you focus on the real as what holds authenticity, you’re led to some kind of ethical digital dualism, mostly concerned with value statements (i.e., isolated from ontology).

@nathanjurgenson it is related : moral decision can only come up if based on something true

— Stéphane Vial (@svial) March 8, 2013

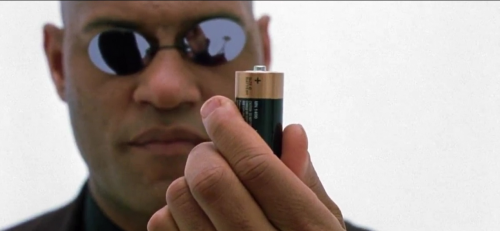

What are the implications of inserting this philosophical dualism within digital dualism theory? I think it is a mistake and not a good solution for the future of digital dualism critique (of which I am a staunch defender from France, following my presentation at the Theorizing the Web 2013 conference). Because, since Plato, ontology has always founded ethics. Only because there are two separated worlds in Plato’s metaphysics can Plato argue on that the philosophers must quit the Cave in order to access the real world. Only because you know that the Conscious and the Unconscious are real can you act as a psychoanalyst in your office. Only because Neo knows that the Matrix is real can he get out from it and change his life. Knowing the truth is the surest way to make value statements and therefore take decisions and actions in your life. It is your idea of the real that determines your actions in life.

Ontology and Ethics are not severable. Just because you refuse to employ the term “real” does not mean that you are not making ontology (and this term is unclear only for Carr). Ontology is not a sham. Ontology is the foundation. “Cultural value statements based on the idea that the on and offline are distinct rather than enmeshed” are more deeply based on ontological fantasies and beliefs. Digital dualism cannot ignore that. When Nathan says:

Thus, digital dualism is the tendency to see the digital and material as too distinct, rather than enmeshed,

he is still discussing ontology. Adding the “too” does not (and cannot) change anything. It is just impossible “to place ontology largely on the back-burner.” Because it always comes from the back to the front with more power, as fantasies do from our unconscious life to our consciousness. Why dismiss ontological digital dualism? Confrontation is inevitable. We must live with it and clarify it again and again. Everyday ontology makes everyday ethics. And, professional ontology makes professional ethics. Even with regards to technology.

I do agree that the goal is not to make ontology because it’s fun to make ontology. The goal is to change mentalities and turn people into digital monists, so that they can act differently with digital media and stop making fallacious statements such as “these kids with their Facebooks are trading reality for the virtual!” When they change their ontological assumption about what is real changes, new value statements, new decisions, and new life experiences–enmeshing more and more the digital and the physical–will be possible.

So, Mr Carr and all digital dualists should wonder this: When our kids become adults, following years and years spent on Facebook and video games, which ideas will they admit as true: digital dualist or digital monist?

I’m Stéphane Vial. I’m a Digital French Theorist at Technophilosophy. And I’m on Twitter [@svial].

This post was directly written in English without any help from my usual translators : please forgive tactlessness. It can be offered to Cyborgology readers thanks to the great editing work from PJ Rey. My warm thanks to him, that’s the way I like sharing ideas across oceans in the age of the Internet.

Notes

1. Jean-Claude Beaune, La technologie, Paris : PUF, coll. “Dossiers Logos”, 1972, p. 5.

2. Don Ihde, Technology and the Lifeworld, Bloomington and Indianapolis : Indiana University Press, 1990, p. 1.