The abstract submission deadline for the Cyborgology “Theorizing the Web 2011” conference had been extended to February 20th. Submit here. Registration also now open.

The abstract submission deadline for the Cyborgology “Theorizing the Web 2011” conference had been extended to February 20th. Submit here. Registration also now open.

This post originally appeared on one of our favorite blogs, OWNI, 25 January, 2011. ![]()

Without indulging into the theories developed by radical sociobiologists, we can reasonably hypothesize that the development of the ego, vanity, and a sense of self-importance were more or less the result of evolutionary adaptations needed for our species’ survival.

THE NATURAL NEED TO EMERGE FROM THE CROWD

In prehistoric times, group survival depended on the level of strength and stamina individuals had in an insecure world where they were powerless against nature. They had to be strong enough to persevere over harsh weather conditions, long migrations, and other dangers in this savage world. They also had to be fit enough to compete against other males for females, thus perpetuating their contribution to the gene pool.

More than just mere strength was needed for survival: The cohesion and solidarity of the groupallowed people to defend themselves against larger animals and organize collective hunts. In turn the group provided food security for everyone, justifying why collective actions were instated as an efficient method for survival.

The final factor in group survival, and according to Darwin the differentiation between humans and other species, is intelligence. This gave way to the development of better weapons for self-defense, the ingenious invention of the needle for making clothes, and the discovery of fire. Intelligence revolutionized man’s potential by making him the master of nature instead of its slave.

In modern times the problem of immediate survival has been replaced by another hazard: the necessity to stand out from the crowd. Thus, people need a more refined skill set that is beyond basic communicative intelligence.

NEW COMMUNICATIONS AS A DIFFERENTIATING FACTOR

NEW COMMUNICATIONS AS A DIFFERENTIATING FACTOR

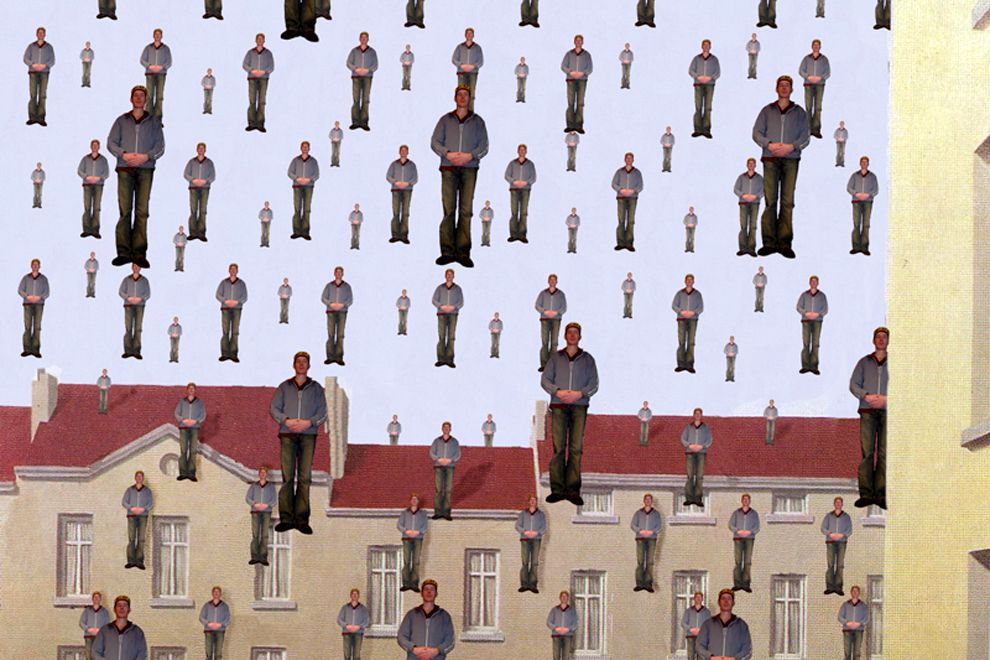

Our lifestyles are becoming increasingly urbanized. Human activity is focused on industrialization, which geographically constrains individuals to the city life. We are constantly surrounded by a sea of other people.

Contemporary life emphasizes a uniformity in lifestyles which is attributed to the homogeneous nature of professional activities. The clone-like employee market has replaced the uniqueness of small trades and vendors, and the only way to be reminded of the incredible economic diversity that can exist is through a trip to India.

This standardization has further been fostered by the “consumer society,” which relies on the mass productions of goods for survival. Who doesn’t have an Ikea “Billy” bookshelf in their house? Our consumer society encourages homogeneity and has sustained through other mechanisms that promote social differentiation (This has been demonstrated by the works of French sociologists Jean Baurillard in “La société de consommation” and Pierre Bourdieu in “La distinction”).

In the last few decades we have created new information technologies such as web 2.0 and social networking sites, leading to an explosion of global interactions. These new technologies are becoming a significant tool with our need to distinguish ourselves in economic, political, and sexual competitions.

With every Facebook status update and every blog post, we are expressing that we are different and unique. We are proving we have value as an object of social and cultural consumption. When having a conversation in everyday life, it is crucial that we are “interesting,” “funny,” or “original.”

However, maintaining this level of uniqueness requires a significant amount of energy. We must become more and more cultured so we don’t run out of things to say. We visit museums, go to the movies, makes crafts and home repairs to cultivate our creativity. The reality is that we must retain the the attention of others, but this social paradigm makes it increasingly difficult to gauge other people’s attention.

THE COMPETITION FOR ATTENTION

Driven by our need for social recognition, we are compelled towards constant action. There must always be something to do: work, read, watch TV, eat, sleep. The fleeting thought of non-action is immediately dismissed (contrary to other cultures, notably Buddhism). I suggest that you watch (or watch again) “Kennedy et Moi” with the great Jean-Pierre Bacri.

Being constantly on-the-go creates a deficit in the attention we give to others. We consolidate our emotional investments and our time for socialization, limiting ourselves to our family, close friends, and coworkers. Thus ensues vicious cycle: the more we are active in the name of socialization, the more scarce global attention becomes and the less likely it becomes to experience real socialization.

Relationships between colleagues benefit from this arrangement because attention becomes “forced.” This probably explains why the bonds which develop in the work environment are so strong, either in a negative or positive sense. There is increasingly more emotional confusions between personal and private relationships, as there are more opportunities for friendly interactions and disappointing encounters.

Then there is also the addition of new media, the new cultural practices. The explosion of video games, computers and social networks are piled on top of older technologies such as the television, radio and newspaper. These new cultural practices squander the time that could be used for real socialization. “You’re not going to put down your Xbox console for a while, are you?”, ”Oh, don’t call me on Thursday, that’s the day I watch my favorite TV show.”

Patrice Le Lay from TF1 preached about the “the brain time available,” which he sold directly to advertisers. While the phrase created a bit of a stir, it was an honest statement; all he did was say aloud the concept which every media company knows to be true.

THE EGO: A DIFFERENT STRATEGY FOR ATTENTION

THE EGO: A DIFFERENT STRATEGY FOR ATTENTION

The mechanisms are not new, but our changing lifestyles and the explosion of new media tools amplifies this phenomenon. We must emphasize this change in order to emerge from the crowd, and because the new instruments afforded to us encourages this behavior. Recently developed electronic tools include blogs, social networking sites, the diversity of communication platforms (Flick’r, Youtube, WAT), interactive sites (Rue89, 20 minutes, Le Post). Furthermore online newspapers are now allowing comments on their websites. The door to the ego and self-expression is officially open.

The new credo is no longer “know how,” but rather just “know.” The Christian values of humility are no longer effective traits in social society. Instead we must keep pushing ourselves above the crowd to have a chance of snatching valuable attention. This is the downfall of many young journalists, who think they can just get by on “personal branding“(which I wrote about in a previous post).

Even if the Internet (like previous information technologies) fails to truly democratize culture and knowledge, at least it is turning into a good platform to promote talent. This accessible system permits individuals to break away from the crowd, including quality bloggers (Maitre Eolas, Hugues Serraf, Versac) and entertainers (Vinvin, Mathieu Sicard). The art of public speaking, which was previously dominated by media elites, can be used by anyone who wants to prove their value and stand out.

THE RACE FOR ATTENTION CREATES FAKE EMOTIONS

The result of this social game is the generation of false statements at emotions in response to the demands imposed on us by society. The rules of the game oblige us to have a façade of happiness, because others value an individual who approaches problems with a smile on their face (but maybe not as much in their brains). This mechanism was correlated with the creation of Japanese Kawii culture (Also a good article on the subject is “l’euphorie perpétuelle” by Pascal Bruckner).

– It’s the permanent care-free state-of-mind, “gone fishing.”

– It’s the exaggeration of positive statements, “I had a GREAAAAAAT weekend!

– It’s the sugar-coated words, “You’re really amazing.”

– It’s the digital humor; to “LOL” is much more trendy than being serious and boring.

On the other hand, maybe cynicism is really a type of symbolic domination over individuals and events. Mocking demonstrates a sense of being external and superior to another object or person.

A NEW SOURCE OF INEQUALITY

In this competition for limited attention, not all individuals have the same chances of success. Only the most interesting, funny, and charming people are spared from the harsh rules of the game.

The people who are mediocre, uncultured, boring, and lack a sense of humor are the first social genocide victims. Like most realities concerning social economic standing, the socially disadvantaged who are uneducated and have not experienced higher culture are the ones that fall behind. It’s this group who don’t see cultural films, don’t go to modern art museums, and thus can’t hold an acceptable conversation or have real value in the eyes of the middle and upper class.

The “no-conversation” community can comfort the socially disadvantaged group. These are the people who strive to renovate the world through unconventional bits of information gathered here or there. These are the youth who congregate on street corners, speak their own language, and follow their own rituals of belonging which reassures they are locked into their own world. ReadEdmond Husserl’s ”phénoménologiste de l’esprit.”

New media is not responsible for the nature of the socially-obsessed ego. Yet the homogeneity of lifestyles, the aggregation of people into city life, and new technologies truly amplifies this phenomenon. So I emerge exactly as who I am…

Cyborgology editors Nathan Jurgenson and PJ Rey discuss the social media connections to this tragedy. The complete interview is now streaming (interview starts at 2:03).

Cyborgology editors Nathan Jurgenson and PJ Rey discuss the social media connections to this tragedy. The complete interview is now streaming (interview starts at 2:03).

Cyborgology editors Nathan Jurgenson and PJ Rey discuss their take on WikiLeaks, net neutrality, and other issue surrounding the free flow of information on the Internet. The complete interview is now streaming.

Cyborgology editors Nathan Jurgenson and PJ Rey discuss their take on WikiLeaks, net neutrality, and other issue surrounding the free flow of information on the Internet. The complete interview is now streaming.

Body modification, a growing practice and subculture that now spans the world, has made extensive gains in merging the body with technology. Stretched earlobes, facial tattooing, and dermal implants have become more conspicuous as of late in many urban locales, and it is no longer surprising to find people going to greater lengths to modify their bodies in sometimes unique and shocking ways. For more examples, spend some time on one of the most popular online body modification community websites, Body Modification Ezine.com. The site documents the diverse array of practices that members engage in to explore, test, stretch, and construct their bodies in new ways. (Warning: The content is not for the squeamish).

Body modification, a growing practice and subculture that now spans the world, has made extensive gains in merging the body with technology. Stretched earlobes, facial tattooing, and dermal implants have become more conspicuous as of late in many urban locales, and it is no longer surprising to find people going to greater lengths to modify their bodies in sometimes unique and shocking ways. For more examples, spend some time on one of the most popular online body modification community websites, Body Modification Ezine.com. The site documents the diverse array of practices that members engage in to explore, test, stretch, and construct their bodies in new ways. (Warning: The content is not for the squeamish).

Particularly, I want to focus in on a few keen examples of the merging of body and technology, or as I call it, the new cyborg body.

First off is the now infamous Rob Spence, a man who successfully implanted a LED light into the cavity of his lost eye. He is something of a legend in the body modification community, mostly because of his unique situation and how he turned to body modification to make the most of it. He lost his eye as a teen and then, several years ago, got this red LED light implanted into the empty cavity. He is currently working to construct the world’s first miniature prosthetic eye camera to replace the current LED light. Arguably, Rob Spence epitomizes of Donna Haraway’s concept of the cyborg—the merging of organism and technology. No longer metaphorical, we now have true cyborgs among us!

First off is the now infamous Rob Spence, a man who successfully implanted a LED light into the cavity of his lost eye. He is something of a legend in the body modification community, mostly because of his unique situation and how he turned to body modification to make the most of it. He lost his eye as a teen and then, several years ago, got this red LED light implanted into the empty cavity. He is currently working to construct the world’s first miniature prosthetic eye camera to replace the current LED light. Arguably, Rob Spence epitomizes of Donna Haraway’s concept of the cyborg—the merging of organism and technology. No longer metaphorical, we now have true cyborgs among us!

In another interesting convergence of body and technology, an increasingly popular trend in the body modification community is to get magnets implanted in your fingertips. These tiny, powerful neodymium magnets are implanted under the skin and allow the individual to pick up small things like nails, paperclips, screws and washers. You can find several blog posts about them on BME.com, as well as several YouTube videos of individuals playing with their finger magnets.

I would argue that body modification, rather than a marginal activity reserved for social deviants, is something that is becoming increasingly relevant to our understandings of the body. Though the origins of body modification lie in urban subcultures, they are becoming increasingly normative for younger generations (think of how many people you know under the age of 25 that have at least some piercings or a tattoo). The body has become the latest terrain for identity construction, as individuals seek to display their individuality and tastes through modification. In addition, body modification is challenging the very notions of the body as an ontological whole and changing how we display and pursue our very selves. No longer is the “body as temple” (as Judeo-Christian belief contends) something that must remain untouched, but something that must be adorned to show our respect and admiration for ourselves. In this sense, body modification serves as but another manifestation of the body projects that contemporary society enforces upon us. In Foucault’s terms, we show our sociality by “disciplining” ourselves in lines with societal standards (think of dieting and exercise as a measure of social competence). And body modification, as a unique form of discipline, is pushing these norms in new directions.

I will be back to share more examples of human-machine interaction in the body modification community. Until next time, here is a list of resources for further reading: Mike Featherstone has written extensively on how the body is now the site of identity construction in late-consumer society; Victoria Pitts has written on the body projects of marginalized groups (LGBT communities and women, specifically) as an effort to resist patriarchal and Judeo-Christian domination; and Gill and Mclean have written on the body projects of men as a form of constructing, negotiating, and policing hegemonic masculinity in contemporary society

For all those folks whose only impediment to climbing Mount Everest has been their inability to Tweet updates while on the journey: your excuses are now dried up. Representatives from Ncell, Nepal’s main mobile network, announced recently that they have installed cellular service that reaches all the way to the top of Mount Everest, the world’s highest point. According to the Reuters report:

“The installation could help the tens of thousands of mountain climbers and trekkers who visit the Mount Everest region in the Solukhumbu district every year. They have to depend on expensive satellite phones to remain in touch with their families as the remote region lacks proper communication facilities.”

This development has interesting implications for the Cyborgology blog’s ongoing discussion of augmented reality and the limits of material experience. When we think about the material world being augmented by virtual content, we tend to think about it in an urban context, usually in tandem with marketing or networking efforts. But how do we begin to think about augmenting the reality that exists in the remotest and most dangerous of regions, like the summit of Mount Everest?

The statistics aren’t entirely clear, but best estimates say that the number of climbers who have successfully reached the summit of Everest only goes into the low two thousands, and at least two hundred of those who have attempted the climb have perished. Most of those who the mountain has claimed remain where they died, frozen into the rock for all time. Some of those bodies are plainly visible from established routes up the mountainside, mummified by the dry air and harsh wind at that altitude. That’s some pretty real reality right there. So how augmented could it get?

Of course, the primary purpose of this technology isn’t Facebooking your awesomeness from twenty thousand feet; this is intended to be a life-saving endeavor that connects climbers to their emotional and physical support systems at the base of the mountain in a way that has never been available before. But you know who else may want that kind of connectivity, or may want their reality augmented a bit? The two-thirds of Nepal that currently lives without any networking capabilities. From the bottom of that Reuters report:

Telecommunication services cover only a third of the 28 million people of Nepal, South Asia’s poorest country… [Major Ncell shareholder] TeliaSonera [will] spend over $100 million to expand its facilities in Nepal next year and ensure mobile coverage to more than 90 percent of the Himalayan nation’s population.

It seems, then, that social class plays a big role in who gets to augment and who gets plain old material reality. Those who climb the mountain are predominantly tourists (though, of course, they are often accompanied by local guides and assistants). These tourists have economic resources not available to local populations; the permit to climb the mountain alone costs nearly US $25,000. This sits in stark contrast to the people of Nepal, who earn a rough annual per capita income of about US $1000.

The question of access is just one more example of how the material world increasingly bleeds into the virtual; because access to virtual resources involves access to material resources, the two are invariably linked. But under these conditions, it appears that, along with elements of augmented reality, we are also importing our uneven power relations from the material world into the frontiers of virtuality.

Last week, Kokoro Co. Ltd. released video of the latest iteration of its work in robotics, taking another step in the process of bridging the “uncanny valley”—the idea that the closer that robots and other non-human objects approach to looking authentically human, the stronger a reaction of revulsion, fear, or mistrust they inspire in their human observers. Kokoro is well-known in the robotics field for creating lifelike humanoid robots capable of recognizing and mimicking human facial expressions and body language. You may recognize the Kokoro name in reference to the I-Fairy, a humanoid robot that presided over a wedding in Japan last summer, and the Geminoid project, where customers can have themselves reproduced in silicone and wire.

The Actroid-F (the ‘F’ stands for female) robot was built and programmed to monitor patients in a hospital setting. Currently, programmers are teaching the robot to mimic patients’ facial expressions, and to recognize the differences in their smiles and grimaces. The result is a very lifelike robo-nurse that can be used to monitor the feelings and needs of hospitalized patients. On the surface, this seems like a good idea; we already use machines to monitor patient vital signs and administer life-saving medicines, so why not use machines to monitor patient morale?

The question I want to pose, however, is why this machine has been given human form. Medical professionals don’t generally feel the need to paste googly eyes on IV drips, or put a mustache on the X-ray machine before scanning a patient. So why should a technology meant to monitor patients’ faces have to look human? If monitoring faces was the only goal here, a webcam and some facial expression recognition software would suffice, and would probably do the job in a much less intrusive or disturbing way. Is there something intrinsic to interacting with machines given human form that would somehow improve the performance of the device?

And what about the fact that the robo-nurse in question is structured to look not just human, but female? This seems to have its roots in normative expectations of what gender a nurse should be, but remember: this isn’t a nurse, it’s a machine. Giving it human form is one thing, but why must it be female? And beyond making the machine female, why must the body we give it be an attractive, normative body?

I’m reminded of Kelly Joyce’s Magnetic Appeal, and her discussion of how trends toward visuality have led doctors, technicians, and patients to give the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machine so-called non-human agency in the scanning and diagnosis of patients. According to Joyce, modern patients put more stock in a visual representation of their health—usually in the form of a magnetic resonance image—than they do in physician opinion. She asserts that medical experts are not immune to this preference; in using the MRI machine to image and assess patients’ health, physicians and technicians will contribute all of the diagnostic and healing power of the MRI to the machine, often valuing the machine’s output more than their own initial assessment. In essence, the tools build the house despite the carpenter, and not because of him.

Is Actroid-F the next step in visuality and non-human agency? Are we now so comfortable giving machines agency in human processes that it now actually makes sense to give them human form?

Cyborgology editors Nathan Jurgenson and PJ Rey discuss their take on “cyberbullying,” the recent rash of teen suicides, and the Internet’s role in providing social support to alienated teens. The complete interview is now streaming.

Cyborgology editors Nathan Jurgenson and PJ Rey discuss their take on “cyberbullying,” the recent rash of teen suicides, and the Internet’s role in providing social support to alienated teens. The complete interview is now streaming.