The mobile phone camera has become an embedded tool of protest. It has given rise to the citizen journalist and is a key mechanism by which surveillance is countered with sousveillance. In a New Media & Society article earlier this year, Kari Andén-Papadopoulos names this phenomena citizen-camera witnessing. This is a ritual through which bodies in space authenticate their presence while proliferating images and truths that contest with the stories told by The State. The citizen camera-witness is not merely witnessing, but bearing witness, insisting upon articulating, through image, atrocities that seem unspeakable. Indeed, as W.J.T. Mitchell compellingly claims: Today’s wars and political conflicts are to an unparalleled extent being fought on behalf of, against and by means of radically different images of possible futures.

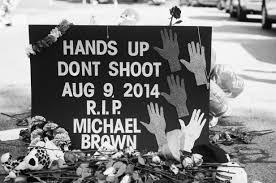

The failure to indict Darren Wilson in the killing of Michael Brown and the protests that continue to follow, set the stage for drastically different futures. The way we tell this story will guide which future is most plausible, most logical, and most likely.

The key image makers include State representatives, mainstream media, Darren Wilson supporters, and those protesting against the Grand Jury decision. These voices vie for space in the construction of the Michael Brown/Darren Wilson story. The story told by those in the first two categories is largely one of violence and mayhem at the hands of an unruly crowd. The story told by Wilson supporters is similar, but with a clear reverse-racism twinge. The story of those in the last category is one of systemic oppression, a story in which black bodies—especially black male bodies—are in persistent danger of physical harm, inflicted by those charged with public protection.

I stand with this last category, and am committed to promulgating their version of the story. But in watching this story and in spreading it, I’m struck by the method of its telling. In particular, the citizen-camera witnesses not only point their camera phones at the crowds, at the police, and at the built environment, but also point the camera at themselves. They don’t merely imply their presence through video footage, but explicitly locate themselves—their own bodies—at the heart of the story.

I want to make the case for citizen-camera witnesses to be thoughtful in their use of this videographic tactic. In particular, I call for these witnesses to consider their own bodies, and what it means to have particular kinds of bodies within the imagescape. I argue that the role of protestors with white bodies, those antiracists who stand in solidarity, should be one of quiet support. White voices and faces already overpopulate public discourse. Absolutely turn your camera outward on injustice. Always do this. But think carefully before turning the camera on yourself.

The war for possible futures, fought in images, has far reaching consequences; for some, those consequences are literally life and death. The stakes are highest for those with bodies of color. These are the bodies in danger. These are the bodies that should be at the center of the story.

Image: Source

Follow Jenny Davis on Twitter @Jenny_L_Davis

Comments 5

Ribbit — November 28, 2014

"I argue that the role of protestors with white bodies, those antiracists who stand in solidarity, should be one of quiet support. White voices and faces already overpopulate public discourse." Yeah . . . and alienating potential supporters with a 'progressive stack' really worked great at Occupy. Remember all those economic reforms you all won there? Brilliant job!

BP — November 29, 2014

We're not "black bodies", we're black *people*.

Anti-Consuming Ferguson » Cyborgology — December 1, 2014

[…] over the weekend, but I think it is fair to assume that some white liberals gave the kind of quiet support that my fellow editor Jenny Davis called for last friday, but I also can’t shake the feeling that […]

Don’t Black Lives Matter? » Feminist Reflections — December 11, 2014

[…] Ferguson: White Bodies Bearing Witness by Jenny Davis, The Society Pages, Nov. 28, 2014. […]