It seems like the science fiction and fantasy community is at a point where every month or so we have some kind of dust-up regarding harassment at conferences and conventions. Some of these have actually stretched over many months, and watching them both from the inside and the outside is always an interesting experience, in part because I’m intimately and personally interested in the outcome, but also because it’s like a giant master class in what not to do, as a conference, when dealing with harassment.

I should note that I’m going to be speaking here primarily as a private citizen, as it were, and not formally as a member of the Theorizing the Web organizing committee. It’s naturally impossible to completely separate myself from that, but this is not an official statement of any kind and should not be read as such. This is just me talking.

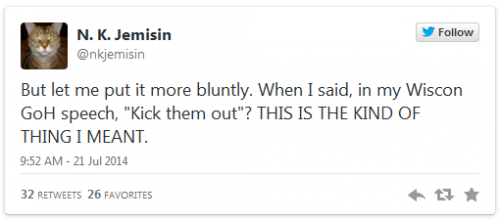

The most recent incident concerns a long-running feminist science fiction and fantasy convention known as WisCon. The story is somewhat involved (here’s a good link roundup) but suffice to say that harassment was reported to the committee and was subsequently very badly mishandled – ironically, given that WisCon bills itself as an explicitly feminist organization dedicated to creating “safer spaces” for marginalized people.

Though, as people of color, trans people, and many others already know, “feminist” spaces are usually hardly safe.

The larger point is that, again, this is not just about WisCon. This issue raises some important questions about what an organizing committee is and what their job consists of. That’s something that the people behind Theorizing the Web has spent a lot of time thinking about in 2014, in part because its anti-harassment statement and its claim to a commitment to construct a safer space was put to the test right out of the gate.

The general consensus seems to be that the situation was handled well, and also served as a very public statement to the effect that business is meant. It also demonstrated a commitment to the idea that “online” and “offline” should be treated not necessarily as the same thing but as spaces in which events potentially have equal weight and value. But there were certain things that made the situation unusual besides, that I think are worth noting.

Most particularly: it was public. Everyone saw it, including and even especially people who were not physically present. There was no need to report. This wasn’t a situation in which a single person was harassed and had to come forward to say so. And those are the situations over which con committees are repeatedly tripping. In part because there may be no record aside from what the victim reports; there may be no other witnesses besides the harasser, or if there are witnesses they may – for sadly excellent reasons – be reluctant to come forward. This can provide excuses for inaction or the protection of “respected” harassers – oh, well, we didn’t know for sure, we had incomplete information, it was their word against his anyway. Harassment done through social media can leave a clear trail, by its very nature. There can be screenshots, other saved documentation – though all too often not even clear documentation helps much. If a committee is already working with a plan of action that’s incomplete or poorly thought-through, or is ultimately far more concerned with protecting committee members than victims, the opportunities for doing things badly out of sight of the public, or of obfuscating things afterward, is not insignificant.

So if Theorizing the Web is committed to taking harassment in digital space seriously, fantastic. It’s about time. But physical space has to be taken seriously as well, because I think in a lot of ways the potential for harm is much greater.

We spent a lot of time and put a lot of thought into the precise wording of our anti-harassment statement. But a piece by Jamie Bernstein at Skepchick reminded me: “Your well-written anti-harassment policy is insufficient.”

We can evaluate the content of the policy and determine the general rate of harassment and culture by attending the con, but what we can’t do is test the con’s methods of dealing with harassment that actually happens and this is where many cons end up failing. Unless you attend the con, are harassed, and then make a report, you have no idea whether the con staff will actually take the complaint seriously or try to sweep it under the rug. Even if a con is generally good at dealing with harassment complaints, what happens when a report comes in that names a harasser that has connections with the staff at the con as happened in this WisCon case? The con may claim that everyone will be treated equally, but it’s impossible to know for sure until it is tested.

Afterward, we said that TtW’s statement had been tested. But it had only been tested a little and in many ways, the test wasn’t actually all that difficult, though in other ways it was. The real test will come when there’s a specific report made to the committee. And I say “when” because it will happen. There’s no way it won’t. Theorizing the Web has a lot more work to do, regarding what its priorities are and the degree to which it plans to stick to them.

I’m optimistic that that important work will be done, and done well. But I’m not about to relax.

Sarah is on Twitter – @dynamicsymmetry

Comments 1

Links: 08/08/14 — The Radish. — August 8, 2014

[…] Anti-Harassment statements – you don’t know until you know […]