The Quantified Self is defined—in the tagline of the movement’s website—as self -knowledge through numbers. With the example of the Tikker “Happiness Watch” (also known as the Death Watch) I argue for the primacy of self-knowledge within the movement, and the subservient role of numbers.

Self-quantifiers utilize technologies to tell themselves, about themselves. The information gleaned through self-quantification practices and technologies are meant to facilitate mindfulness, which facilitates control, which facilitates change in a desired direction. For instance, if a FitBit tells its user how many calories s/he consumes and burns, the user is made aware of hir consumptive practices, exercise patterns, how these relate to body size, and what s/he can do to maintain or alter that body size to accomplish greater or lesser mass. The technologically induced numbers, however, are those which serve a human purpose. It’s less about the technology, less about the numbers, and more about how self-quantifiers use them for their own desired ends. That is, technological measurements of the body serve at the pleasure the desired self. This becomes quite clear with the example of the Tikker watch.

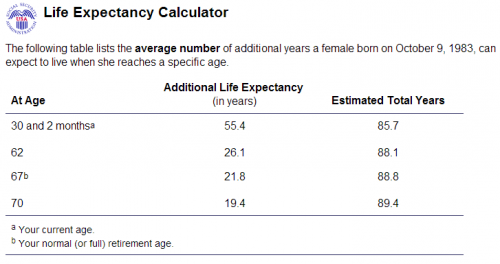

The Tikker, as a technology, tells the user very little about hir body. This is a watch which calculates the user’s average life expectancy, and then counts down the minutes until anticipated death. It also tells time, for what that’s worth. The algorithm for life expectancy is drawn from that used by the U.S. government, and is based quite simply on age, sex, and your cohort’s life table. As a woman of 30 years and 2 months, I have about 55.4 years left to live. If I were a man, that drops to 51.8 years.

The technical aspects of the watch are incredibly simplistic. It takes a calculation based on age and gender, and then it counts down. One’s age and gender are the only pieces of personalizing information. It ignores lifestyle, biography, family history, environment, etc.(not to mention excluding anyone with queer gender identification). More concretely, my estimated 55.4 years ignores that my college apartment offered free tanning facilities (knock of several years), that I run or otherwise work out 6 days per week (add on a few), that my diet is almost entirely vegetables (add a few more), but that I finish every night with an ice cream cone (knock off a couple). It ignores my grandmother who lived to 92, and my grandfather who never hit 80. It forgets the grey hairs I developed while studying for comprehensive exams, and that weird stint of almost daily cheap-beer consumption. In short, the Tikker nods to the body, in a nominal way, while concentrating significant focus on the mind. Indeed, the creators refer to this as a “Happiness Watch,” and tout it as a product which will make the world a better place. And of course, they suggest that the watch will make better people out of those who wear it. The following is taken from the website:

While death is nonnegotiable, life isn’t. The good news is that life is what you make of it – and it can be beautiful!

All we have to do is learn how to cherish the time and the life that we have been given, to honor it, suck the marrow from it, seize the day and follow our hearts. And the best way to do this is to realize that seconds, days and years are passing never to come again. And to make the right choices.

Anger or forgiveness? Tic-toc. Wearing a frown or a smile? Tic-toc. Happy or upset? Tic-toc.

THAT’S WHY WE’VE CREATED Tikker, the death watch that counts down your life, just so you can make every second count.

Really, the Tikker is not much different than putting an inspirational saying on your bathroom mirror. It reminds you to live a certain way, focuses your energies on this lifestyle mentality, and encourages you to remain reflexive, always mindful of who you are, who you want to be, and how you have to live to get there. The only difference is that the Tikker has moving parts, a timer heading consistently and imperviously closer to zero. But this clock, these moving parts, are largely symbolic. They have little to do with the body of the person who employs it. This technology quantifies the self inaccurately, but these inaccuracies are of little consequence, as the numbers are but tools in the pursuit of a particular kind of mindfulness; a particular urgency of life.

Follow Jenny Davis on Twitter @Jenny_L_Davis

Comments 1

Friday Roundup: Jan. 10, 2014 » The Editors' Desk — January 10, 2014

[…] Tikker: The Death/Happiness Watch on Cyborgology […]