Between the emotion

And the response – T.S. EliotMistah Kurtz– he dead. – Joseph Conrad

I’ve spent the last two posts in this series building up a background set of claims regarding a) how the stories we tell about war have changed over time, and b) how the relationship between technology and war has changed in the last century, particularly as regards different forms of simulation. These are important points to make, but they’ve also been leading up to what I want to talk about this week: specific examples of war-themed video games and the stories they’re telling, and what difference it all makes.

I want to also note at this point that I’m not out to make any kind of conclusively causal argument. I’m not interested in claiming that video games definitely change how we think of war, or that how we think of war definitely shapes what kinds of games we play, or that either have anything definite to do with how we actually fight the wars we choose to fight. I think any or all of those are interesting arguments, but I also don’t think I have the data to support strong statements about them either way. Instead, what I want to suggest – and what I’ll be employing specific examples in support of – is simply that there’s Something Going On at the intersection of simulation/technology, culture, storytelling, and war, and that this Something is probably worth further thought and investigation.

A primary indicator of a story’s power to shape meaning is its prevalence – how many people are telling it how many times and in what context. It makes sense, therefore, that if we’re going to look closely at what might be happening at the point of intersection I refer to above, we should focus at least in part on war-themed games that have enjoyed considerable popularity.

(I should offer another caveat here: this is by no means and in no way a representative sample. If you wanted to write a truly thorough examination of war-themed video games and American culture, it would take the space of a book to do so. But I think these are revealing cases, albeit a small n.)

Within the genre of war-themed games, very few titles in the last decade have enjoyed the kind of success that the Call of Duty games can claim. The initial entries into the CoD series were set in WWII – as have been many other games – and to refer back to my first post in this series, I think a lot of that can be attributed to how we think of that war. Comparisons can be drawn between WWII games and films, with the themes of noble sacrifice and heroism, and a Manichean standoff between good and evil discussed above. World War II has been described as “the last good war”; this makes it a culturally comfortable reference point for imagining what armed conflict is like.

But CoD‘s most popular titles have been more contemporary in terms of setting – CoD 4: Modern Warfare and its two sequels have been immensely popular, with the first MW selling in excess of 13 million units worldwide. For the purposes of this piece, I’ll be focusing on the first two installments in the series.

Both MW and MW2 put the player in the point-of-view of different soldiers at different points in the story, both US Special Forces and British SAS. Both games also emphasize concepts that are vaguely consistent with what has been calledthe “New War” theoretical approach – the idea that regarding war in the latter half of the 20th and the early 21st centuries, states are less important, and that the borders between state and state, between soldier and civilian, and between state actor and non-state actor are increasingly porous. In both games, the player’s enemy ranges from an insane Middle-Eastern warlord who has masterminded a coup, to the leader of a Russian ultranationalist paramilitary group; in each case it’s understood that the enemy is not a state as such. Indeed, the movements of states often feel abstract and distant from the action in which the player finds themselves involved, however important they might be to the overall plot (indeed, at one point in MW2 the player takes part in a battle between the US and an invading Russian force; however, Russia is invading in retaliation for a terrorist attack perpetrated by Russian ultranationalists and framed on the United States). The player engages in small military operations, fighting against other small groups of soldiers, often to retrieve vital pieces of intelligence or personnel.

Despite the blurriness of combat identities and the de-emphasizing of state-level actors, the actions of the various soldiers that the player personifies are framed by other characters – such as commanding officers – as important, even crucial to the stability of the world. Some of this can be explained through simple narrative convention: in order to engage the player in the story, the player needs to feel that the action in which they are taking part is supremely significant in some way. But some of it also resonates with contemporary understandings of war, with decisive action taking place on a micro rather than a macro level, in small-scale conflicts rather than on massive battlefields between entire armies.

Another thing that makes MW and MW2 so noteworthy is what they suggest about what is permissible in war. MW2 in particular takes a brutally casual approach to the torture of detainees in one scene, where, after you have captured one of the associates of the game’s main villain, you leave him with your fellow team members. As the camera pans away, you see your captive tied to a chair with a soldier looming over him, holding clamps that spark with electricity. While your character does not carry out the torture, the torture is implied to have both taken place, and is implicitly presented as both necessary and reasonable. The game narrative encourages acceptance of this rather than questioning of it, partly because the action proceeds so rapidly from that point that meditation on what has occurred is not really possible. It’s worth noting at this point that game narrative, action, pacing, and design are often difficult to distinguish without doing violence to their meaning; in this case they’re one and the same. A particular narrative interpretation of a particular event is emphasized at least in part because of the mechanics of cutscenes and gameplay.

To turn back to the issue of nobility and sacrifice in war films, it is interesting to compare some of what I discussed in part I of this series with the first two installments of Modern Warfare. Sacrifice in older American war films – particularly death in battle, particularly for the sake of one’s comrades – is regarded as noble, sacred, and not to be questioned. It’s regarded as worthy in itself, and a worthy act by worthy soldiers fighting for a worthy cause at the command of worthy generals and political authorities.

MW and MW2 fall somewhere between war as depicted in heroic war films and in tragic war films. Soldiers, especially the soldiers the player takes on the role of, are presented as competent, well-trained, courageous, and effective, as well as possessing at least a surface-level knowledge of the significance their actions have. When SAS Sergeant John “Soap” MacTavish attacks Russian ultranationalists, he knows that it is because they are seeking to acquire a nuclear missile with which to threaten the US – he further understands that the situation is exacerbated by post-Cold War instability as well as a military coup in an unnamed Middle Eastern nation. When, in the same game (MW), USMC Sergeant Paul Jackson is sent to the Middle East to unseat the author of the coup, he understands that nuclear proliferation is the same threat, and that he and his comrades are literally defending the safety of the world. When, in MW2, you take on the role of Sergeant Gary “Roach” Sanderson and seek to capture a Russian criminal by the name of Vladimir Makarov, you understand that he has authored the instigation of an invasion of the continental US by Russia—while, back in Washington DC, Private James Ramirez literally defends the capital from foreign troops. None of this is in question, and the characters are both informed of their mission’s importance and committed to seeing it carried out. Suffering and sacrifice for the sake of that mission are depicted as noble (though of course, if the player character is killed – with several exceptions that I will address – the game is over). Traditional patriotic values are not questioned in either game.

In MW,when Paul Jackson and his comrades attempt to push through an advancing wave of enemy soldiers to rescue a downed Apache pilot, the player is clearly meant to be moved by their courage and their loyalty to each other. In MW2 the scenes of an invaded Washington DC – complete with a burning Capitol and White House – are clearly meant to be horrific by virtue of being nationalistic symbols that have been injured and destroyed by an enemy force, while the soldiers fighting to push back the invaders are brave defenders of the homeland.

However, where the games both approach tragedy is in their depiction of the essential senselessness in war, and of the betrayal of soldiers by their commanders. In Modern Warfare, Sergeant Paul Jackson succeeds in rescuing the downed pilot, only to have his own helicopter brought down by the shockwave and ensuing firestorm when the warlord in charge of the country detonates a nuclear bomb. In one of the most haunting – and unusual – sequences of the game, the player crawls from the wreckage of the helicopter, struggles to his feet, and looks around at a burning nuclear wasteland before dying of his injuries. There is no way to survive the level, no weapons to wield and no one to kill, and not even really anything to do but to exist in that moment and bear witness to horror before expiring. The way the narrative frames the sequence is fairly clear: Paul Jackson is a heroic man engaged in a worthy fight, and yet the tragedy of his death is that it’s fundamentally senseless.

Likewise, at the end of his last successful mission to one of Makarov’s safehouses, Sergeant Gary “Roach” Sanderson is brutally murdered by his commander, Lieutenant General Shepherd, who is revealed to have been using Roach and his comrades for his own ends. Again, there is no way to survive the episode; the betrayal of a soldier by his commander is part of the story and cannot be avoided. The plot element differs from much of what one finds in tragic war films in that both the soldiers on the ground and the ideals for which they fight are depicted as essentially honorable; it’s the men in power who should be questioned and held up for suspicion.

This last is especially telling, given a number of the dominant narratives that have emerged out of the Iraq War – that of American troops acting in good faith but betrayed by negligent and/or greedy politicians and commanders. In that sense, Modern Warfare is folding one narrative into another in a kind of shorthand; by now, this is a story with which we’re all familiar on some level, which makes it available for the game’s writers to use in a play for the player’s emotions. Deeper characterization isn’t necessary; you never really get a clear sense of who any of these people are. Deeper understanding of the geopolitics behind what’s happening is likewise de-emphasized; though the actions of the player’s character might be of immense importance and the character himself seems to understand why he’s been given the orders he has, all the player really needs to know is that they’re important, not why they’re important. The cultural shorthand of “betrayed soldier” is all that really matters, and once it’s been employed, the game can and does move on.

It’s important at this point to examine the question of choice, and how choice is understood to function within video games, particularly games about war. Choice in gaming has become something of a selling point; witness the proliferation of sandbox games, as well as games that at least attempt to present the player with some kind of narratively meaningful moral decision-making (see Bioshock and Bioshock 2). But what’s interesting about games like Modern Warfare is what they suggest about the choices that a player doesn’t have.

Someone who plays a video game is interacting with a simulated world, and the rules of that world dictate what forms of interaction are possible with which aspects of the game world. Game code determines how a player moves, what they can touch and pick up, what they can eat or use as tools—and what they can injure or kill or destroy. This is additionally significant because when a certain action is permitted on a certain object, code—the rules of the game—often dictates that it is the only action that can meaningfully be performed on that object. An object in the game world that can be consumed can frequently only be consumed; there is no other possible use for it. Likewise, a character in the game world that can be killed can often only be killed; with exceptions, they cannot be talked to, reasoned with, or negotiated with, and inaction on the part of the player usually leads to the player’s demise and the end of the game. Especially in combat-themed first person shooters, the rules are often quite literally as simple as “kill or be killed”, and regardless of danger to one’s character, destruction of some kind is commonly necessary to advance the game action. War as depicted in video games is therefore war without real agency: fighting and killing an opponent is the only rational or reasonable course of action, if not the only one even possible. Game code is not neutral; it tells a story, it sets constraints on how that story can be interpreted, and it determines what forms of action are appropriate or intelligible.

The thing for which Modern Warfare 2 is probably best known is the infamous “No Russian” level. In this level, the player has infiltrated a group of Russian nationalist terrorists who plan to open fire on civilians in an airport. They then do just that – and the player cannot stop it. They can take part in the slaughter or they can stand by and do nothing, but they can’t save anyone, and they can’t fire on the terrorists. The player is therefore being explicitly put in a position where agency is poignantly lacking (recall the nuclear wasteland level in MW), where civilians scream, beg for mercy, and attempt to crawl away, all while the player can do nothing narratively meaningful.

But the player can still shoot. The fact that they’re holding a weapon and can make use of it is significant in itself – there is agency, just agency of a particularly horrible kind. Mohammad Alavi, the game designer who worked on No Russian, explains it this way:

I’ve read a few reviews that said we should have just shown the massacre in a movie or cast you in the role of a civilian running for his life. Although I completely respect anyone’s opinion that it didn’t sit well with them, I think either one of those other options would have been a cop out… [W]atching the airport massacre wouldn’t have had the same impact as participating (or not participating) in it. Being a civilian doesn’t offer you a choice or make you feel anything other than the fear of dying in a video game, which is so normal it’s not even a feeling gamers feel anymore…In the sea of endless bullets you fire off at countless enemies without a moment’s hesitation or afterthought, the fact that I got the player to hesitate even for a split second and actually consider his actions before he pulled that trigger– that makes me feel very accomplished.

Essentially, the player can’t prevent horrible things from occurring. The most they can reasonably expect is to choose to participate in those things – or not. But when player agency is whittled down to that level, player responsibility also erodes; why should there be any sense of responsibility, given that one is playing in a world where the parameters have been narrowly set by someone else?

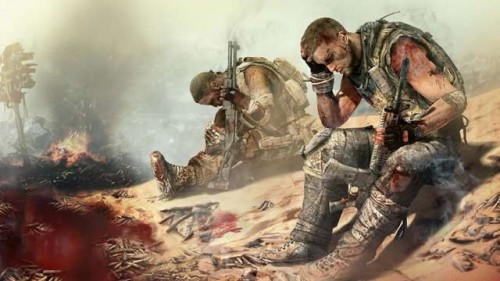

A more recent game that has some serious points to make regarding player agency is Spec Ops: The Line, a contemporary rehashing of Apocalypse Now, (which is itself of course a retelling of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness). Gaming writers have noted that it’s a game that seems to have active contempt for its players, drawing one in to thinking it’s a fast, flashy, Modern Warfare-style shooter before pulling the rug out and revealing to the player that every action they’ve taken since the game’s beginning was in fact utterly reprehensible. It’s a game that purports to be a giant comment on its own genre, and its success in doing so has apparently been mixed.

But one primary thing on which Spec Ops seems to comment is the question of what choices a player actually has in a war game – and, by extension, what choices a person has in a scenario like the one the game depicts. The player, the game seems to be saying at multiple points, has no choice; by choosing to play the game at all – by choosing to enter the scenario – they’ve locked themselves into a situation where not only is there no real win-state, but there is no inherent significance to any of their actions. The game – and the world – is not working with you but against you. Walt Williams, Spec Ops‘s lead writer, puts it this way:

There’s a certain aspect to player agency that I don’t really agree with, which is the player should be able to do whatever the player wants and the world should adapt itself to the player’s desire. That’s not the way that the world works, and with Spec Ops, since we were attempting to do something that was a bit more emotionally real for the player…That’s what we were looking to do, particularly in the white phosphorous scene [where a group of civilians is mistakenly killed], is give direct proof that this is not a world that you are in control of, this world is directly in opposition to you as a game and a gamer.

Video game blogger and developer Matthew Burns takes issue with this, pointing out that the idea of the removal of choice leading to a massacre of civilians has intensely troubling implications, not only for games themselves but for how we as a society understand the question of choice in extremis:

I present a counter-argument: in the real world, there is always a choice. The claim that a massacre of human beings is the result of anyone– a player character in a video game or a real person– because “they had no choice” is the ultimate abdication of responsibility (and, if you believe certain philosophers, a repudiation of the very basis for a moral society). It is unclear to me how actually being presented with no choice is more “emotionally real,” because while it guarantees the player can only make the singular choice, it is also more manipulative.

This, then, is what I think is the central question around video games, simulation, storytelling, and war: How do we understand the very meaning of action? How true is it that we always have a choice, and if we do – or don’t – what does that mean for responsibility, on the level of both individual and society? I argue that when we play games, even if we’re not playing very close attention to the story – even if there isn’t really very much of a story to speak of anyway – we still internalize that story on some level. We interpret its meanings and its logic; we have to, in order to move within its world. We are participants on some level, even if the extent of our participation is the experience of the gameworld. And when we’re participants in a story, that lends the story greater weight for us than if we’re merely passive observers – to the extent that one can ever be passive within the space of a story.

Like other forms of media, war-themed video games are arenas for reproductions of certain kinds of meanings and narratives about our culture and our wars. But more than that – and perhaps more than other forms of media – they are spaces for conversation and debate over how we process those meanings, and what it truly means to participate in something. In these games we talk about patriotism, honor, and sacrifice. But we also question ethics, choice, and the significance of death – and we as participants are brought uncomfortably close to those questions, not only in terms of the questions themselves, but in terms of what it means to ask them at all, and in the ways that we do. And as Spec Ops and No Russian reveal, many of the answers we find are intensely troubling. As Matthew Burns writes:

I played through No Russian multiple times because I wanted direct knowledge of the consequences of my choices. The first time through I had done what came to me naturally, which was to try to stop the event, but firing on the perpetrators ends the mission immediately. The next time I stood by and watched. It is not an easy scene to stomach, and I tried to distance myself emotionally from what was going on.

The third time, I decided that I would participate. I could have chosen not to; I could have simply moved on then, or even shut off the system and never played again. But a certain curiosity won out– that kind of cold-blooded curiosity that craves the new and the forbidden. I pulled the trigger and fired.

Also highly recommended:

Comments 1

Your Questions About Call Of Duty Modern Warfare 3 Hardened Edition | Top Ten Most Popular Christmas Toys For 2012 List — October 18, 2012

[...] for as low as $35. Keep looking maybe you'll find it for a better price.Powered by Yahoo! Answers Jenny asks…call of duty modern wafare 3?what should i buy the Standard edition of call of duty mod...>what should i buy the Standard edition of call of duty modern warfare 3 or should i get the [...]