Crossposting:: An abridged, less sociology-heavy version is here.

Notes from north of 49ºN.

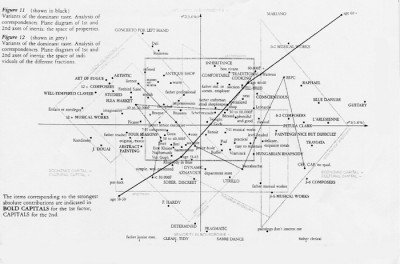

Social capital is nothing new to ThickCulture, with quite a few posts on the topic, including this one by José, Trust is for Suckers. When I teach sociology, I draw heavily on Pierre Bourdieu and have the class get a sense of how different forms of capital interact. Cultural capital has always interested me {here’s a great overview of it by Weininger & Lareau}, despite going crazy trying to explain graphs like these::

I’ve used this very graph, but I’ve always wanted a way to engage students in a discussion of cultural capital that they could relate to. So, I was catching up on Macleans reading and found articles on Canada’s smartest cities. It brings up an interesting question of how learning capacity affects the local economic development. The Composite Learning Index, using ideas developed by UNESCO, gauges a city’s ability to foster lifelong learning::

“Until now, Canada’s score had been on the upswing, from 76 in 2007 to 77 last year. Today that number has dropped to 75, precariously close to the lowest level recorded, which was 73, in 2006. The figures are based on the annual Composite Learning Index, which gives every Canadian community (some 4,719 in all) a score according to how it supports lifelong learning.“

“Quebec City’s unemployment has fallen markedly, from 6.8 per cent in 2006 to 5.2 per cent in 2009. And while Windsor’s total learning score was going nowhere, its jobless rate shot up, from 10.2 per cent to 15.2 per cent over the same period.“

- Embodied. The skills, abilities, & knowledge that someone has.

- Objectified. The objects that transmit culture and knowledge.

- Institutionalized. Institutional recognition of an individual’s skills/abilities/knowledge.

Twitterversion:: #newblogpost Hey Canada…How smart is your town? @macleansmag article on Composite Learning Index popularizing sociology? http://url.ie/1qkn @Prof_K

Song:: Town Called Malice – The Jam

Video::