Later today, on my other blog, rhizomicon, I’ll be doing a post on the semantic web {web 3.0}, which stems from work I’m doing in the area of semantic web and social media. In my research this morning on information ontologies, I came across Debategraph, a collaborative visualization tool that maps ideas/concepts in the realm of complex policy issues. Here’s a demo video::

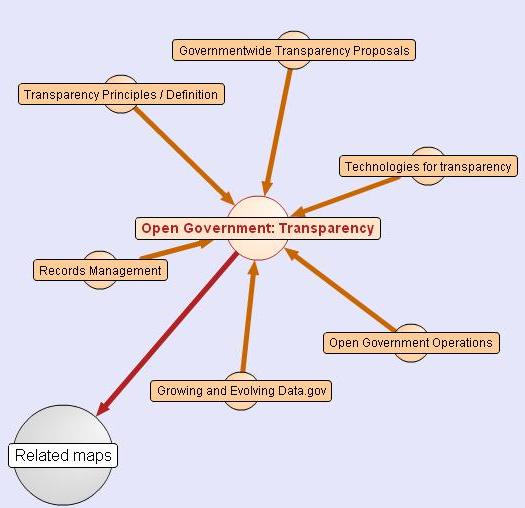

The Obama administration used Debategraph for their open government brainstorm last year. You can access the Debategraph here::

A friend of mine once convened meetings on watershed management in the SF Bay Area and this type of technology would have been very useful in the consensus-based planning recommendation model being implemented. While the loud and the cantankerous could attempt to be a thorn in the side at the public meetings, it would be harder to withstand the criticism of most of the other stakeholders. Nevertheless, there is the persistent wiki problem of how status and legitimacy affects deliberation and in this instance, policymaking. What I do like is how content can be uses and repurposed in online collaboration 24/7. I was thinking of semantic web implications in policy, but that’s for another time.

Maybe the State Department should explore this to flesh out transparency policy in light of the recent Wikileaks.

Twitterversion:: Thoughts on Debategraph visual mappings of ideas 4 transparent complex policy deliberation, used by Obama admin last year @ThickCulture @Prof_K