Notes from North of 49ºN

Last Friday, the Torontoist listed its 2009 “Heroes & Villains” and one of the heroes was the mandatory 5¢+ fee for plastic bags {for all retail} that went into effect on June 1st. A columnist for the Toronto Star, Peter Gorrie, called it a sham, but his arguments are based on a logic that doesn’t account for behavioural change, i.e., a reduction of consumption and use of disposable bags, as people adjust to not using them. He made several assumptions::

- Plastic bags aren’t a major environmental hazard, in terms of garbage load and marine hazards

- Manufacturing plastic bags use fewer resources than paper

- Plastic bags can be re-used by consumers

He makes the following point, though::

“If the nickel fee makes us more aware the bags do have value and carry a slight environmental price tag, fine. If that prods us to consider using less of everything, even better. At most, though, it’s a potent symbol of how we embrace the trivial instead of doing what’s really required.”

I get where he’s coming from, but I don’t think he’s on the right track.

- Diverting petroleum resources away from disposable bags that wind up in landfills or in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch by reducing consumption makes both economic and environmental sense. If the policy in aggregate reduces consumption and conserves finite resources, at the expense of convenience, it’s a win in my book.

- This assumes that the policy will not curb demand for disposable bags of all kinds. I’m not aware of Toronto retailers shifting to paper.

- While plastic bags can be re-used for other purposes, does the existence of a secondary use warrant unconstrained continued usage? This assumes a demand for plastic bags for all purposes that is unyielding.

More interesting is the quote above, as he wants the public to have more real consciousness about reducing consumption, which is a good thing, but feels the tax embraces the trivial. This is where social science comes in.

Prospect theory is part of the field of economic psychology, developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, which serves as a rival theory to the rational expected utility model, which is prevalent in economics. Prospect theory is richer and more robust {sounds like a coffee} than expected utility, as it has greater explanatory power. A cornerstone of the theory is how people treat gains and losses differently. The classic example used is which do you prefer::

- a 2% credit card surcharge -or-

- a 2% cash discount

So, let’s create a hypothetical example. There’s a camera that a retailer sells at a cash price of $100 and a credit price of $102, i.e., two prices depending on the terms of payment. Which would consumers prefer::

- A stated price of $102, but with a cash discount price of $100

- A stated price of $100, but with a credit card surcharge of $2, so the credit price is $102

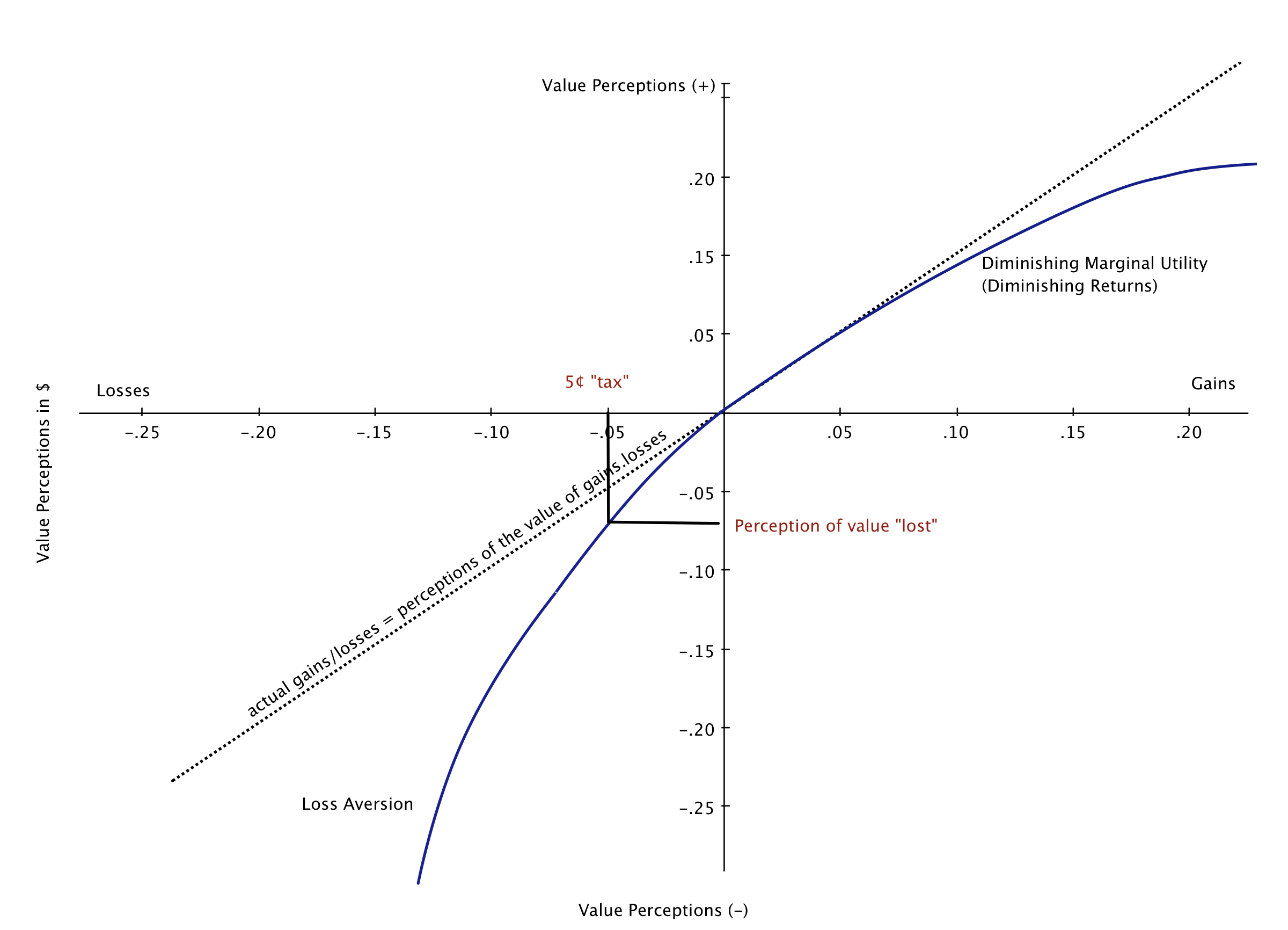

These are equivalent scenarios, but most people don’t like the surcharge and prefer the cash discount. It’s viewed as a “loss” that people will often go to great lengths to avoid and in prospect theory this is called loss aversion. On the other hand, as gains increase, they are valued less, which fits economists’ “law” of diminishing marginal utility. These perceptions open the door for framing effects.

Who cares, it’s just 5¢, right? The 5¢ charge is effectively a tax on using an economic “bad” or environmental externality and the consumer perceived the loss of wealth to be greater than the 5¢. It’s the money plus a wee bit of a psychological carrying charge to boot. The consumer once got bags for “free” {actually the cost was imputed in prices}, but now must either furnish their own bags {diminished convenience} or pay 5¢ per bag {out-of-pocket costs}, so now they are subject to losses. The loss aversion means the 5¢ can serve as a big disincentive for their use, particularly in a recessionary economy. One supermarket chain, Metro {Dominion} instituted a 5¢ fee across Ontario and Québec, resulting in a 70% reduction in plastic bag use. What this tells me is that the status quo wasn’t entrenched and the policy is helping to alter behaviours. What I’m hoping is that policies like this help to reduce the 4B plastic bags handed out annually, just in the province of Ontario.

Whoa, hold the phone. Why not offer cash back for not using plastic bags? Looking at the prospect theory graph, refunds for not using plastic bags aren’t perceived to be worth it. In aggregate, getting a few nickels back is perceived to be worth less than the money, so many consumers may not feel compelled to change their behaviour.

In terms of a plastic bag surcharge policy, the carrot loses to the stick.

Twitterversion:: @Torontoist 2009 “hero,” the 5¢ plastic bag fee, is a policy that follows sound social science theory, based on Nobel laureate’s work. @Prof_K

Song:: The Submarines-“Modern Inventions”