This blog post is part of a series on Malcolm Gladwell’s New Yorker article on how social activism during the Civil Rights era is categorically different from activism using social media. Malcolm Gladwell’s controversial piece in this week’s New Yorker is shaking things up, as he’s advocating that social media doesn’t lend itself well to social activism. He cites examples of how social media only fosters surface-level, low-commitment actions based on weak ties and that social movements, like those pushing for civil rights, require hierarchies. I disagree. Others have, as well, as John Hudson has compiled over on The Atlantic. I’ll focus on Gladwell’s take on weak ties in this post, which I find problematic due to his sweeping generalizations of ties and their potential in guiding everyday life. The Nature of Ties Gladwell claims that social media fosters weak ties::

“There is strength in weak ties, as the sociologist Mark Granovetter has observed. Our acquaintances—not our friends—are our greatest source of new ideas and information. The Internet lets us exploit the power of these kinds of distant connections with marvellous efficiency. It’s terrific at the diffusion of innovation, interdisciplinary collaboration, seamlessly matching up buyers and sellers, and the logistical functions of the dating world. But weak ties seldom lead to high-risk activism.”

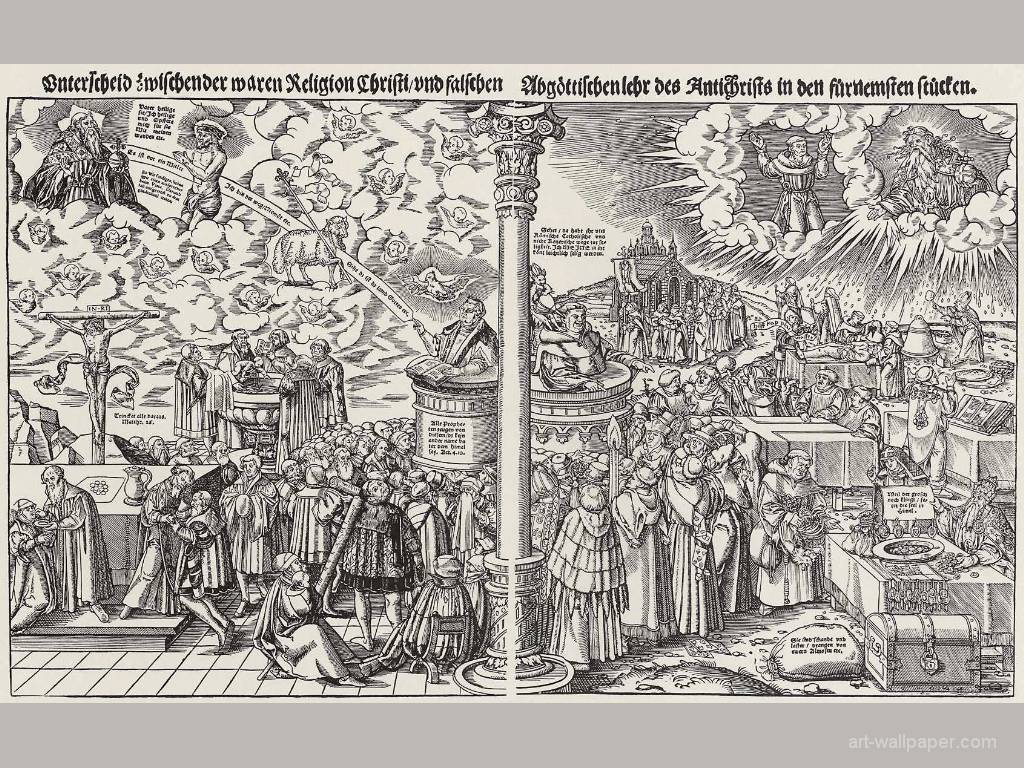

Others have critiqued this by stating that social media tools {like Twitter and Facebook} can foster more than weak ties. Network structures are combinations of both weak and strong ties. The organizational research of Brian Uzzi at Northwestern {see image above} found that there are dangers of being overembedded {too many strong ties leading to insularity} and being underembedded {too many weak or arms-length ties leading to a lacking of social structure}. Gladwell’s critique on this front hinges upon characterizing all networks as underembedded networks. There’s another issue here, which is the content of the tie. Ties can be characterized as strong or weak, but they can also be multiplex, i.e., representing a complex relationship that has more than one channel. For example, a tie can be characterized by flows of different types of capital, e.g., social, economic, political, etc., with varying degrees of strength. Social media campaigns can and do tap into networks and use people’s multiplex ties to increase engagement. Hearing about an issue through someone in your network is often more persuasive than from media and advertising, so there’s great potential here, but going from a social media campaign to action, let alone social change, is far from automatic.

My next post will address the issue of motivation and social media. Gladwell doesn’t think social media motivates people, but drives participation. I question this puzzling sweeping generalization.

I’ve been thinking about José’s blog on

I’ve been thinking about José’s blog on