Crossposted on Rhizomicon.

Just a short blog, as I’m on the road en-route from Toronto to San Francisco for ASA. So, I got into Iowa City around 9PM last night and I saw a tweet from CBC, linking to a story on the “mastermind” behind Pranknet, Tariq Malik. The Smoking Gun goes into great deal outing Pranknet {with media clips} and their nefarious activities and BoingBoing and Canoe.ca have a short articles on the matter.

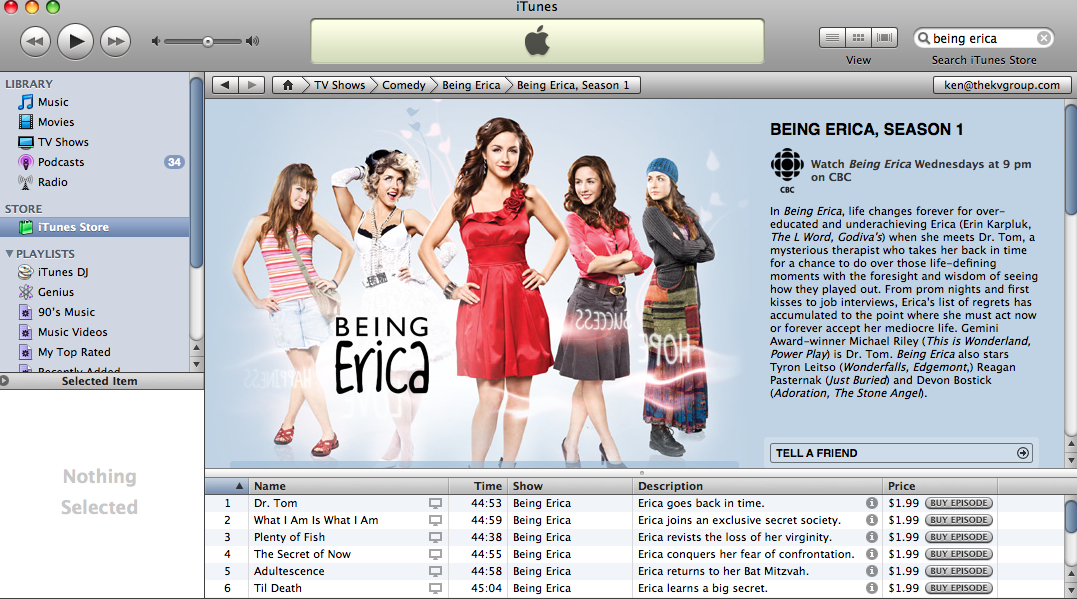

Over the holidays, I saw CBC really hyping

Over the holidays, I saw CBC really hyping