What does it mean to pay for an idea? James Gliek reminds us that one of Google’s main business innovations was to:

let advertisers bid for keywords—such as “golf ball”—against one another in fast online auctions. Pay-per-click auctions opened a cash spigot. A click meant a successful ad, and some advertisers were willing to pay more for that than a human salesperson could have known. Plaintiffs’ lawyers seeking clients would bid as much as fifty dollars for a single click on the keyword “mesothelioma”—the rare form of cancer caused by asbestos.

While Google keeps its ads and its search results distinct, the lines between a “market meaning” and a “public meaning” are becoming blurred. With Google claiming two-thirds of the search market in the United States, does Google have a disproportionate power to define what things mean.

Google has a cryptic algorithm that relies on links from other authoritative and non-authoritative sites to establish page ranks. But as David Segal points out in the New York Times, these rankings are subject to manipulation through black hat search optimization. JC Penny was able to become the authoritative purveyor of thousands of products using this approach:

If you own a Web site, for instance, about Chinese cooking, your site’s Google ranking will improve as other sites link to it. The more links to your site, especially those from other Chinese cooking-related sites, the higher your ranking. In a way, what Google is measuring is your site’s popularity by polling the best-informed online fans of Chinese cooking and counting their links to your site as votes of approval.

But even links that have nothing to do with Chinese cooking can bolster your profile if your site is barnacled with enough of them. And here’s where the strategy that aided Penney comes in. Someone paid to have thousands of links placed on hundreds of sites scattered around the Web, all of which lead directly to JCPenney.com.

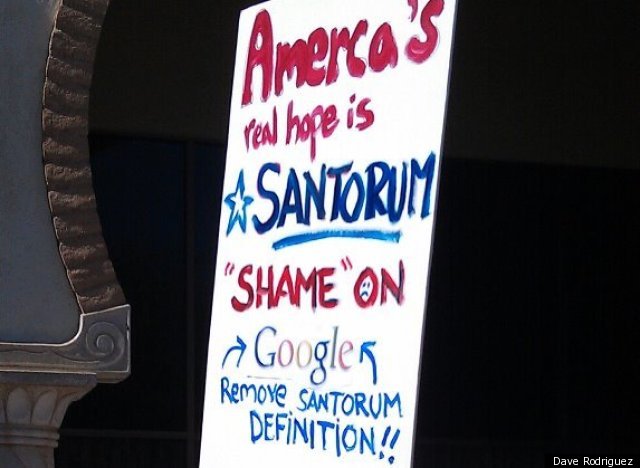

This might produce a big “so what?” if we’re talking about where to buy high thread count sheets, but what if we’re talking about non-commercial definitions. As an example, supporters of Rick Santorum have called on Google to remove an untoward definition of “spreading Santorum” aimed at lampooning his anti-homosexuality positions. While the original blog post with the link is no longer on the first page of search results, a search for the Senator’s name still produces ample references to “spreading Santorum” (links excluded).

While many readers will have little sympathy for his position on gay marriage, I’m sympathetic to supporters who seek to have some control over how the candidate is defined by people who search Google to learn more about their guy. Some might applaud this as a form of hactivism. But tampering with definitions is akin to having your worst enemy write an encyclopedia entry about you that sits right next to the entry you write about yourself. If Google increasingly frames how we “know the world,” then do the spoils go to those who know how to game the system.

Comments 2

wilmont_proviso — March 6, 2012

Another reason to quit using Google. There are other alternatives that are not as fanatical about OUR personal information and search habits.

Does anyone question why Google is making money off of other people's content? Think about it: Google does not create content, we the users do. Google just devours that content as it scours the web, records what we say on our Android phones, logs what we do when we access its programs and services, then Google indexes it, Google analyzes it, and then Google has the gall to charge us for our own content in order for Google to make money.

» Poverty Is Poison — April 20, 2012

[...] [...]