Notes from North of 49ºN

This is a follow-up post to:: Postcolonial Canada, National Identity, & the Nature of Hegemony :: The Trajectory of Canada. This post will focus on the political implications of the current postcolonial circumstance.

Around Canada Day last summer, I talked about the role of media in terms of nation and globalization. I was contemplating the concepts of “nation” and “citizen” within the sphere of North American capitalism. If nation doesn’t matter, do we just become consumers?

In my last post, I echo these ideas, but derived my thoughts on the “fuzziness” of Canadian identity by rooting it in its postcolonial circumstance. The concept of Canada as a nation is problematized by its history and trajectory; going from a colony of Britain with a sizeable minority culture {Québec} to being a next-door neighbour to a superpower. This isn’t to say that Canada has no identity. Ask “Joe” from the classic I Am a Canadian Molson ads series. This one is titled “Rant”::

While within the context of the cultural product of advertising, I find the ad interesting, as it plays upon the notion of Canada as stereotyped and misunderstood by its powerful neighbour to the south. It juxtaposes Canada by delineating what it is not—the United States. The ad inspired several parodies, including this one from a Toronto radio station titled, “I Am Not Canadian”, which illuminates stereotypes of Québec. At any rate, I think there is a Canadian identity, but I’m not sure how unified it is across the country.

Perhaps one of the products of fuzzy identity is a steady trend of increasingly decentralized federalism since WWII. This set the stage for the rise of regionalism, perhaps starting with Québec opting out of federal programmes. Decentralized federalism also means that Canada as an institution will have less and less meaning over time. Pragmatically, it opens the door up for political gridlock::

“There is disagreement not only between the provinces and the federal government, but also among the provinces themselves. Canadians are losing patience with the endless cacophony. They want high-quality services, delivered in ways that are transparent so that they can track results. They are pragmatists. Fix it, they demand. When it doesn’t get fixed, they grow impatient with institutional gridlock.” [1]

Perhaps a product of this impatience is tuning out. Canadian voter turnout has been the lowest it’s been in 100 years, in the low to mid 60s the 00s and dipping to 58.8% in 2008. Moreover, decentralized federalism could explain the fragmentation of politics we’ve seen of late, which I’ve blogged about over on Rhizomicon, characterized by 35% of the popular vote not going to the major parties. Decentralized federalism forces much of the national political discourse on domestic issues to focus on the provincial or regional implications of policy. One of my observations is the rise of regional politics in Québec and the West.

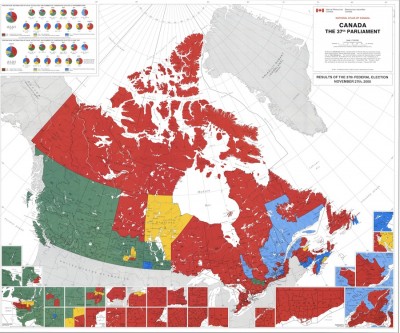

Here’s a map of the 2000 federal election, before the Progressive Conservatives and the Reform/Canadian Alliance parties merged to form the Conservative Party of Canada in 2003, but after the formation of the Bloc Québecois in 1991::

- Canadian Federal Election Map, 37th. General Election, 27 November 2000

In the West, the Canadian Alliance {green} won 66 of 301 seats in Parliament, while in Québec, the Bloc Québecois {light blue} won 38 seats. The predecessor to the Canadian Alliance , the Reform Party, was a socially and fiscally conservative populist party that had the bulk of the support in the western provinces of Alberta and British Columbia, making inroads into Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Its policies and rhetoric were, at times, very divisive and anti-Québec, as evident in this ad campaign from the prior election in 1997::

“[Preston] Manning and Reform were roundly criticized by the other candidates when they ran an ad saying politicians from Québec had controlled the federal government for too long.

Chretien [Liberal Party leader], Charest [Progressive Conservative leader] and Duceppe [Bloc Québécois leader] are all from Québec, and the prime minister of Canada for 28 of the last 29 years has hailed from the province. Still, the assertion led to denunciations of Manning as ‘intolerant’ and a ‘bigot,’ though it seemed to play well in his Western base.” [2]

The Reform “style” members of Parliament of the Conservative Party, who are primarily in the West, have effectively formed a Western “Bloc,” as some argue that the policies of the Conservative Party are heavily influenced by the Reform wing. additionally, the Conservative Party has less of a stake in federalism, which frees them to serve regional interests.

Where does this leave Canada in term of its future trajectory? I don’t see identity formation occurring overnight and I see the likelihood of increased political fragmentation based on region and ideology {given the rise in support of the New Democrats and the Greens since 2000}. In light of this, it may be time to think about more centralized federalism, but the challenge will be how to configure it without a serious crisis at hand. On the other hand, what about leadership? Does strong leadership with results give the electorate meaning, a sense of identity, and increased civic engagement?

Twitterversion:: Thoughts on rising politics of region in Canada, stemming fr.”fuzziness” on concept of Canada as a nation #ThickCulture http://url.ie/4r5l #ThickCulture @Prof_K

References::

[1] Stein, Janice G. (2006) “Canada by Mondrian: Networked Federalism in an Era of Globalization.” Banff Forum. Accessed 24 January 2010, http://banffforum.ca/common/documents/Reading_polit_sust_stein.pdf

[2] CNN (1997) “Canada poised for vote that may deadlock parliament”. Retrieved 21 January 2010, from http://www.cnn.com/WORLD/9706/01/canada.elex/index.html

Comments 7

sarah palin — December 18, 2010

The place for spirited political dialogue. Folks of all political stripes welcome.

ashwin — October 30, 2018

If you have any idea and you are using windows 10 OS then help me to know about this issue how to change pc name in windows 10 and share all the important steps with me. Thank you so much.

Kacy Angel — December 21, 2018

A political region is a geographical area impacted and controlled by a group of people, for example, a country, a state, a county, a territory, a commonwealth. I would say that it is organized for affordable assignment writing service the purpose of collecting tribute or taxes. It most definitely has a monetary element, for example, the European Union.

essays writers — November 4, 2019

This post is very intereting for reading! Thank you for sharing with us! If you happen to look for a writign help then I recommen dyou to apply to the essay writign service for help.

jonan sha — January 24, 2021

nice post like it

bamu alio — January 24, 2021

nice post like it

paseeeg paseeeg — January 24, 2021

good work