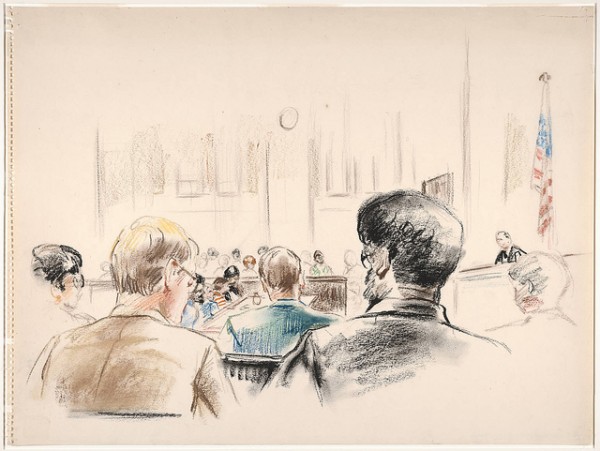

Since the late 1980s, a new type of “special court” has emerged in the United States. These are problem solving courts that aim to provide treatment instead of punishment – attempting to reduce future contacts with the criminal justice system. Drug courts were the first type to emerge and have proliferated by the thousands over the last three decades. In turn, the drug court model spawned a variety of specialty courts focused on other issues, including problems of mental health and domestic violence and the challenges faced by military veterans. As these new specialty courts have spread across the country, researchers have investigated their effectiveness and probed to see why many offenders seem to do well in such programs. Here I summarize what has been learned so far.

How Specialty Courts Operate

Each specialty court provides programming that is designed to address underlying issues that bring groups of offenders to court in the first place. Drug courts, for example, offer services that support sobriety, such as individual and group counseling and twelve-step programs. They also require participants to appear for frequent drug tests. Mental health courts provide access to a psychiatrist and to psychotropic medication as well as to individual and group counseling. Where needed, specialty courts attempt to connect offenders to additional services such as help with housing and education as well as training for employment. more...

Research to Improve Policy: The Scholars Strategy Network seeks to improve public policy and strengthen democracy by organizing scholars working in America's colleges and universities. SSN's founding director is Theda Skocpol, Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology at Harvard University.

Research to Improve Policy: The Scholars Strategy Network seeks to improve public policy and strengthen democracy by organizing scholars working in America's colleges and universities. SSN's founding director is Theda Skocpol, Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology at Harvard University.