Stand Your Ground laws are suddenly in the spotlight, as Americans debate whether they counter violence or put more people in danger of death or injury by gunfire. It is a good time to look closely at what these laws do – and what we know, so far, about their effects.

Expanding the Concept of Self-Defense

The doctrine of self-defense is a time-honored legal defense, but the boundaries of the doctrine are constantly changing. Historically, some U.S. states said that a person had a “duty to retreat” before using deadly force in self-defense. The “Castle Doctrine” said that this duty did not apply when a person was attacked in his or her own home. And since 2005, 23 states have adopted “Stand Your Ground” laws that formally extend the Castle Doctrine to public places, making it easier for a person to use deadly force when he or she “reasonably fears” serious injury at the hands of another. In such a case, the person may be entitled to immunity from criminal prosecution or civil liability. In effect, these laws confer police powers on private citizens, without requiring the kind of training and accountability that police have.

The Trayvon Martin Case

Florida was the very first state to pass a Stand Your Ground law, and the current national controversy erupted after teenager Trayvon Martin was shot dead by George Zimmerman on the night of February 26, 2012, in Sanford, a small city in central Florida. Martin, an unarmed 17-year-old high school student, was walking home from the store in a gated community when he was tracked down and, after an altercation, shot to death by Zimmerman, who was acting as a volunteer neighborhood watchman. The local police initially released Zimmerman, but after a broad public outcry he was later charged and tried for Martin’s death. On July 13, 2013, a six-person jury acquitted him of second-degree murder and of manslaughter charges. Though Zimmerman did not invoke the Stand Your Ground law in response to the criminal charges (he may yet rely on it in any subsequent civil trial), the trial focused on possible interactions between Zimmerman and Martin the night of the events, and the judge’s instructions to the jury echoed the statute’s language: “If George Zimmerman was not engaged in an unlawful activity, and was attacked in any place where he had a right to be, he had no duty to retreat and had the right to stand his ground and meet force with force, including deadly force if he reasonably believed that it was necessary to do so to prevent death or great bodily harm to himself or another…”What if, instead of a Stand Your Ground law, Florida required people like Zimmerman to attempt retreat before using deadly force in self-defense? Perhaps the altercation could have ended less tragically, or even been avoided altogether, if Florida law placed more limits on the use of deadly force. Indeed, on that fateful night, Zimmerman called 911 and was advised by the operator to let the police handle the matter. If he had followed that advice, Trayvon Martin would have been questioned by a patrol officer and most likely allowed to walk home unharmed. The case raises other questions as well. What if Martin had been a middle-aged white man rather than a black teenager? Or what if Florida had tighter rules about gun permits? Zimmerman could have been denied a concealed carry permit, because he had previously been arrested for assault on a police officer and had a history of domestic violence. Perhaps most interesting, what if Martin had killed Zimmerman? In that scenario, Martin might well have invoked the Stand Your Ground law to claim he was not engaged in any unlawful activity, was attacked by Zimmerman in a place where he had a right to be, and reasonably believed that deadly force was necessary to defend himself.

The bottom line is that Stand Your Ground laws – dubbed “Shoot First” by critics – make it easier to get away with what would previously have been considered criminal homicide. Because legal presumptions favor defendants, the prosecution has the burden of disproving the survivor’s story, a hard thing to do if the defendant has killed the only witness.

Stand Your Ground Laws and Gun Violence

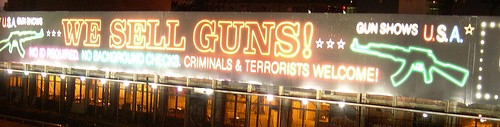

The National Rifle Association promotes and defends concealed carry and Stand Your Ground laws, using arguments that resonate with many Americans who worry that police cannot defend them. Proponents argue that Stand Your Ground coupled with a right to carry concealed guns make criminals think twice about attempting a carjacking or a rape – or even a bar fight – because they know that intended victims enjoy the legal right to shoot them. However, the best empirical work suggests otherwise. One recent study by economists Cheng Cheng and Mark Hoekstra at Texas A&M, and another by economists Chandler B. McClelland and Erdal Tekin at Georgia State University, both conclude that Stand Your Ground laws do not result in reduced rates of assault, robbery, or rape, and have the costly effect of increasing homicide rates.

In evaluating costs, we should also consider that Stand Your Ground laws may encourage the spread of guns. Florida, for example, has issued over one million concealed-carry permits, with issuances tripling since Stand Your Ground passed. Some might celebrate this as creating a well-armed civilian police force. But police are required to have training in handling weapons and dealing with threats, and they are subject to internal rules as well as legal restraints whenever they discharge a weapon. As Miami’s former chief of police John F. Timoney explains: “Trying to control shootings by members of a well-trained and disciplined police department is a daunting enough task. Laws like ‘stand your ground’ give citizens unfettered power and discretion with no accountability. It is a recipe for disaster.”

Undermining the Criminal Justice System

The Tampa Bay Times has done a superb job of documenting nearly 200 cases in which defendants asserted Stand Your Ground claims, resulting in dismissals 70% of the time. In nearly a third of the cases, explains the Times, “defendants initiated the fight, shot an unarmed person or pursued their victim – and still went free.” Judges appear uncertain about the boundaries of the doctrine, and court outcomes are inconsistent. Defense attorneys now make Stand Your Ground claims in hundreds of cases per year. They have a strong incentive to do so, because the burden of proving the defendant did not feel threatened now falls on the prosecution.In short, Stand Your Ground laws encourage the use of deadly force. These laws open the door to a more dangerous world where everyone feels pressure to carry a gun – and if they feel threatened, to shoot first and tell their stories later.

Research to Improve Policy: The Scholars Strategy Network seeks to improve public policy and strengthen democracy by organizing scholars working in America's colleges and universities. SSN's founding director is Theda Skocpol, Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology at Harvard University.

Research to Improve Policy: The Scholars Strategy Network seeks to improve public policy and strengthen democracy by organizing scholars working in America's colleges and universities. SSN's founding director is Theda Skocpol, Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology at Harvard University.