The United States has a long and troubled history with violence, from the slaughtering of the American Indians to the American Revolution to the gun culture of the Wild West (that, in many ways, still remains). Comparisons with other wealthy, English-speaking nations such as Australia, Ireland, and the United Kingdom highlight the country’s unique position: levels of violence, as indicated by national homicide rates, are currently at least four times greater in the U.S. than in these other countries. And that’s relatively good news: in the early 1990s, this gap was as much as seven times larger.

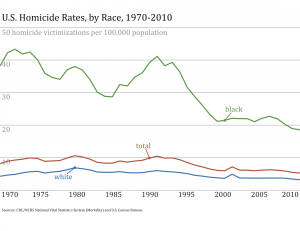

These patterns represent lethal violence in U.S. society overall, but they mask enormous disparities by race, and the U.S. has a long and troubled history there, too. How have overall levels of violence and differences across racial groups changed over time? The answers are most reliably found in data from death certificates collected by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Looking over the data from the last four decades, we can see the entire U.S. homicide victimization rate divided by race. The extraordinary toll of serious violence on the black community is readily apparent.

From 1970 through the early 1990s, the total homicide rate for all U.S. citizens hovered around 10 per 100,000. Since 1993, the rate has declined steadily. In 2010, it was down to just over 5 per 100,000—a “crime drop” phenomenon that has been widely publicized. The trends for blacks and whites largely mirror this pattern; homicide victimization rates have fallen for both groups. But the absolute levels are sharply divergent. White rates have always been below 7 and have now fallen to a historic low of 3 per 100,000. In contrast, blacks experience homicide victimization at 6 to 7 times the rates of whites. Even more dramatically, between 1985 and 1993, black homicide deaths rose sharply, an increase attributed by many to the crack epidemic and the presence of guns in the hands of young people in U.S. cities. Other, non-lethal but violent crimes reveal similar patterns over time and by race.

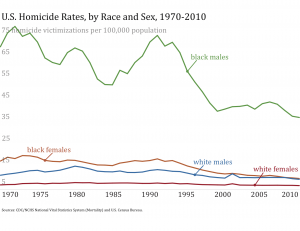

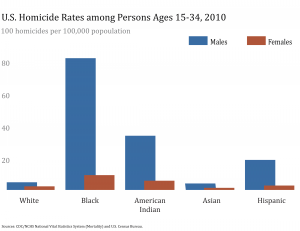

Black males suffer from the highest levels of violence overall, but the picture is worse for young black males. At its peak, the black male homicide rate was over 70 per 100,000, while the rate was two to three times higher for young black men. In the third figure, we display the homicide victimization rates for young males and females of different racial-ethnic backgrounds in 2010 to illustrate the unique burden of violence borne by young black men.

Even now, when overall murder rates are at their lowest level in forty years, the homicide victimization rate for black men ages 15 to 34 exceeds 80 per 100,000. This is more than double the rate for Non-Hispanic American Indian men, nearly four and half times that for young Hispanic men, and more than 17 times that for young non-Hispanic white and Asian men. As a result, murder is the leading cause of death among young black males. Their likelihood of being murdered has real implications for black males’ life expectancy.

By contrast, the leading cause of death for both young white and Hispanic men is accidental death, followed by suicide for whites and homicide for Hispanics. Females are less likely than males to be homicide victims, regardless of race-ethnicity, but the gender differential is much larger for blacks overall and among young adults.

Leading explanations for the “homicide divide” emphasize how the high levels of economic disadvantage present in segregated black communities increase social and economic isolation. That is, poverty is believed to diminish the resources that hold communities together and keep crime at bay. Thus, heightened rates of lethal violence against blacks are not due to greater individual tendencies toward violence; rather, these deaths are the product of socioeconomic disadvantage and societal racism. High rates of incarceration that are particularly concentrated in black and other minority neighborhoods exacerbate these problems by straining families and destabilizing communities. To overcome the prevalence of violent death in the black community will take nothing short of national-level change, including new approaches to income inequality, segregation, and the disproportionate incarceration of minorities.

Comments 1

Friday Roundup: August 2, 2013 » The Editors' Desk — April 1, 2014

[…] “Social Fact: The Homicide Divide,” by Lauren J. Krivo and Julie A. Phillips. Murder is the most common cause of death among young black males. Here are the facts. […]