“Will Obama win?” It’s the question that keeps Chris Matthews and Bill O’Reilly alike awake at night (poor Chuck Todd hasn’t slept in years). As the 2012 presidential election creeps up, members of the pundit class are beginning to lay bets on the number of electoral votes and the popular vote, mostly relying on some combination of polling data and their “gut instincts” to make their predictions. But what drives the polls?

In an admittedly anecdotal sampling of the cable news channels, I’ve found the talking heads seem to assume the big factors are the state of the economy and the President’s likeability. Social scientists, however, are quick to point out that this simple equation leaves out a few key variables.

In a famous wise-old-man essay (though an empirically-driven one) by political scientist John Zaller, cable news pundits are seen as caught up in the day-to-day political mud wrestling, while public opinion about the President is driven by three “political fundamentals”: peace, prosperity, and moderation. That is, the public wants relative peace (or at least the perception of it), a strong economy, and politically moderate leadership. Zaller writes, “Politicians who can fulfill these demands thrive and those who can’t are returned to public life, more or less regardless what the media say about it.” This would, for example, explain why Bill Clinton survived the Monica Lewinsky scandal: the public was far more interested in the fundamentals of the economy than his affair.

So, what does Zaller’s theory suggest for Obama’s chances?

Peace

Americans don’t like “peaceniks,” but they also don’t want a war with major American casualties, says Zaller. Instead, “voters… like presidents who can keep the country’s enemies at bay without having to fight them in wars.” President George H. W. Bush’s short and victorious Operation Desert Storm was a boon for his polling numbers because Americans tend to rally around their leader in war time and the mission saw few American fatalities.

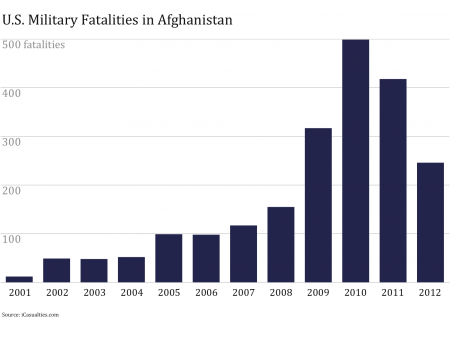

Obama, on the other hand, ran for president in the midst of two unpopular wars that drew daily American body counts (to say nothing of enormous human costs to civilians in Iraq and Afghanistan). He promised to end both. For better or worse, he made good on his word to end U.S. involvement in Iraq. By contrast, he doubled down on Afghanistan. U.S. occupation continues today, with more fatalities in 2010 (499 U.S. military deaths) than during the entire Bush era. Using Zaller’s theory, the ongoing war in Afghanistan should jeopardize Obama’s re-election chances.

Still, compared to the Vietnam War, we are seeing few U.S. military fatalities (16,592 in 1968 vs. 499 in 2010, the peak year of death in each war). Further, the human costs of the Afghan war are borne unequally: a disproportionate number of American troops are people of color (who, voting-wise, skew hugely toward Obama) and from lower income families (who vote at lower rates). In other words, the most likely swing voters are the least likely to be affected directly by the war’s casualties. And finally, to great extent, the economic downturn has pushed the war off the front page. In some ways, for great swaths of the country, the war in Afghanistan is an invisible one.

On the fundamental of peace, I think it’s a mixed story for Obama.

Prosperity

The economy is the central issue of this election. In fact, according to James Carville’s famous formulation (“It’s the economy, stupid!”), the economy is the central issue of every election. More sophisticated analysts, like The New York Times’ Nate Silver, incorporate economic data into their election prediction models precisely because of the belief that, as Zaller writes, “…the incumbent party does well in presidential elections when the economy is good and poorly when it is bad.”

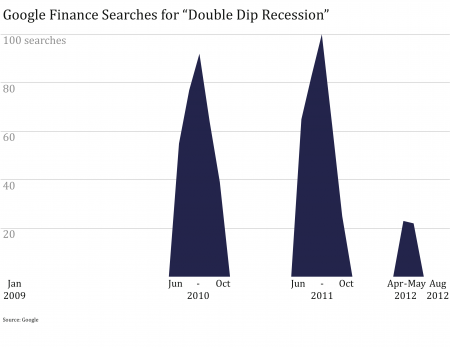

Well, the economy is bad. That bodes poorly for Obama. However, most Americans realize that the president “inherited” the worst economy since The Great Depression. Recent economic indicators (like new jobs added, consumer spending, Dow Jones growth, etc.) suggest we are on a very, very slow path to recovery, and, as the graphic at right illustrates, fears of a “double dip recession” seem to have subsided (though probably not so much in Paul Krugman’s household). For many households, the economy’s getting better, if not as fast as we’d all prefer.

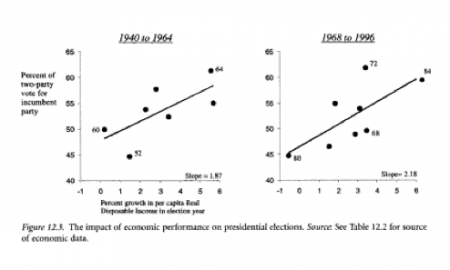

That said, it’s not that much better. While the affluent have largely recovered stock losses and returned to the work force, families on the lower end of the economic scale are mired in a recession. And to hear Mitt Romney and the Republicans tell it, the Obama administration’s policies are actively suppressing growth (accounting for its glacial pace). Using Zaller’s own charts of the impact of economic performance on presidential election (Figure 3), a recently reported 0.3% growth in disposable income would be expected to deliver about 47% of the popular vote to Obama—a resounding loss.

It’s important to remember here that there’s significant debate about the accuracy of economic factors in predicting electoral outcomes. Though he includes them as part of a model based primarily on polling data, Nate Silver has convincingly demonstrated that economic factors are erratic predictors at best. Still, the condition of the economy undeniably shapes the public’s voting decisions. Despite his critiques, Silver estimates that our current rate of growth puts Obama on track for a 50-50 shot at re-election (while an overall model gives Obama a 69% chance of winning the Electoral College).

So, taking a broad look at the economy, it is, once again, a mixed case for Obama’s re-election.

Moderation

Americans are suspicious of ideological extremes. There may be problems with the presumption that “the truth is always in the middle,” but, the public’s preference for moderate politicians seems apparent.

Zaller, though, is most tentative in his defense of the importance of moderation on polling. He writes, almost shyly, “It is, however, difficult to find unambiguous evidence of it [because] presidential candidates are increasingly aware of the importance of moderation and so rarely stray from the middle of the ideological road.” With such a small sample of immoderate candidates, empirical analysis is challenging, but in later research, working with Larry Bartels in the wake of the 2000 election, Zaller did find a small (but non-significant) effect of moderation on the population of presidential elections. By contrast, in 2008, Andy Gelman and Cexun Cai used theoretical models to show that the Democrats could stand to benefit on election day by moving slightly farther to the left. Slightly left, slightly right, or extremely moderate, Americans clearly like their politicians somewhere near the center.

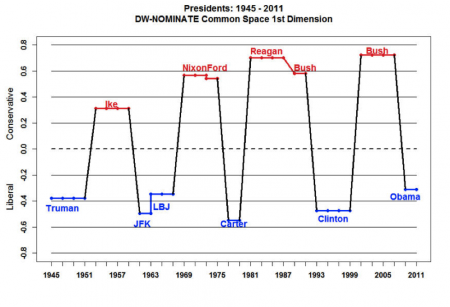

This fundamental should be a slam-dunk for Obama. According to political scientist Keith Poole’s quantitative analysis, Obama is the most moderate Democratic president of the 20th century and the most centrist of all presidents in the past 50 years.

Still, perception can be more important than reality. Since the earliest days of his presidency, Republicans and well-funded conservative Super-PACs have waged a shock-and-awe campaign to brand Obama as a radical, anti-American socialist. Newt Gingrich called Obama “the most radical president in American History,” and the idea seems to be sticking with 59% of likely voters in a Rasmussen poll.

For his part, Obama has fought back by calling Mitt Romney “radical.” Romney’s risky choice of no-nonsense conservative Paul Ryan as a running mate made the incumbent’s efforts to label the Republican ticket ”immoderate” a little bit easier. And though empirical evidence on this point is shaky, it is quite clear that the political players themselves believe it’s crucial to paint their opponent as standing outside the political mainstream.

The Tally

Whatever the reality may be, even on this final measure of moderation, Obama may not seem like a clear choice to voters. In the aggregate, using Zaller’s three “mainsprings of American politics,” the race looks very close. And even to those who aren’t considering political calculus, it seems like a nail-biter. If more of the electorate sees Obama as a moderate who ended the war in Iraq and is slowly bringing the economy around, we can expect a second-term president. But reminders of the ongoing violence in Afghanistan, the still-high unemployment rate, and Obama’s decision to support same sex marriage (seen in some quarters as an exceedingly immoderate position) are top of mind on election day, John Zaller would advise the Cabinet to start looking for work, even in this slippery economy.

Recommended Reading

Andrew Gelman and Cexun Cai. 2008. “Should the Democrats Move to the Left on Economic Policy?” The Annals of Applied Statistics.

Douglas Hibbs’ quantitative forecast model, which uses growth in per capita disposable income and U.S. military fatalities to predict an easy Romney win.

Nate Silver. March 26, 2012. “Models Based on ‘Fundamentals’ Have Failed at Predicting Presidential Elections,” FiveThirtyEight, New York Times Blogs.

Votematic.org, Drew Linzer’s quantitative forecast model using presidential approval ratings, GDP growth, and incumbent control. This site is very optimistic about Obama’s chances for reelection.

Voteview.com, the blog of political scientist Keith Poole, creator of a quantitative system of measuring politician’s ideology.

John Zaller. 2000. “Monica Lewinsky and the Mainsprings of American Politics,” in W. Lance Bennett and Robert M. Entman, Mediated Politics: Communication in the Future of Democracy.

Comments 1

Emily — September 18, 2012

Taking a look at the election through a structural lens was an interesting spin. Most of what's put into the news is a presidential popularity contest with a few tainted facts added in. It was good to have a look at the numeric facts applied to the three faceted theory.

I also find it interesting how varied the interpretations of economic success during Obama's present term are. Clearly he inherited a broken economy, but whether he repaired it adequately is so debated. It's so unclear how that will bode for him in the upcoming election.

Hats off to him for speaking in favor of gay rights, though.