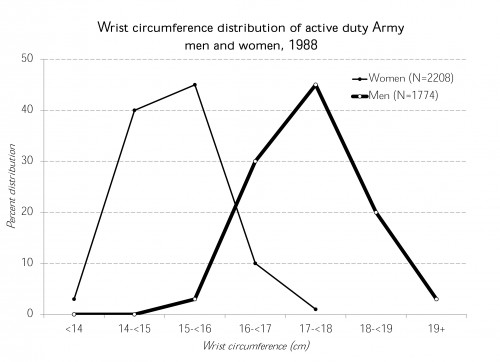

One criticism of my post on gender dimorphism in Disney movies was that good animation inevitably exaggerates sex differences. There are a lot of these comments here on SocImages and at Slate. Here’s one example:

Cartoons aren’t meant to accurately portray people, EVER. They are meant to exaggerate features, so that they are more prominent and eye catching. So feminine features are made more feminine, and masculine features are made more masculine. … The less realistic the proportions, the more endearing and charming we find the character. The closer to realistic they are, the creepier/blander they can become.

Flipping through IMDB’s list of the top 500 animated movies reveals that Disney is certainly not alone in emphasizing the larger size of males. But there are a few successful counterexamples as well.

Here are some good ones where the male and female characters are similarly proportioned. Note these are not just random male and female characters but couples (more or less).

From Kiki’s Delivery Service by Hayao Miyazaki:

From Dreams of Jinsha:

Even some old Disney movies have romantic moments between physically-similar males and females. The original Snow White (from the 1937 movie) was paired with a Prince Charming whose wrists were barely bigger than hers:

Disney non-human animal pairs were sometimes quite physically matched. Consider Bambi and Faline (Bambi, 1942):

Or Dutchess and O’Malley from Aristocats (1970) in which their exaggerated femininity and masculinity are not conveyed through extreme body-size difference:

In other realms of animation, Marge and Homer Simpson, the most durable couple in animation history, have very similar features: heads, eyes, noses, ears. His arms are fatter and neither of them really have wrists, but I’d put this in the category of normal sex difference:

Of course, Lucy and Charlie Brown were virtually identical if you think about it:

I’m open to other suggestions.

Cross-posted at Family Inequality and Pacific Standard.

Philip N. Cohen is a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland, College Park, and writes the blog Family Inequality. You can follow him on Twitter or Facebook.