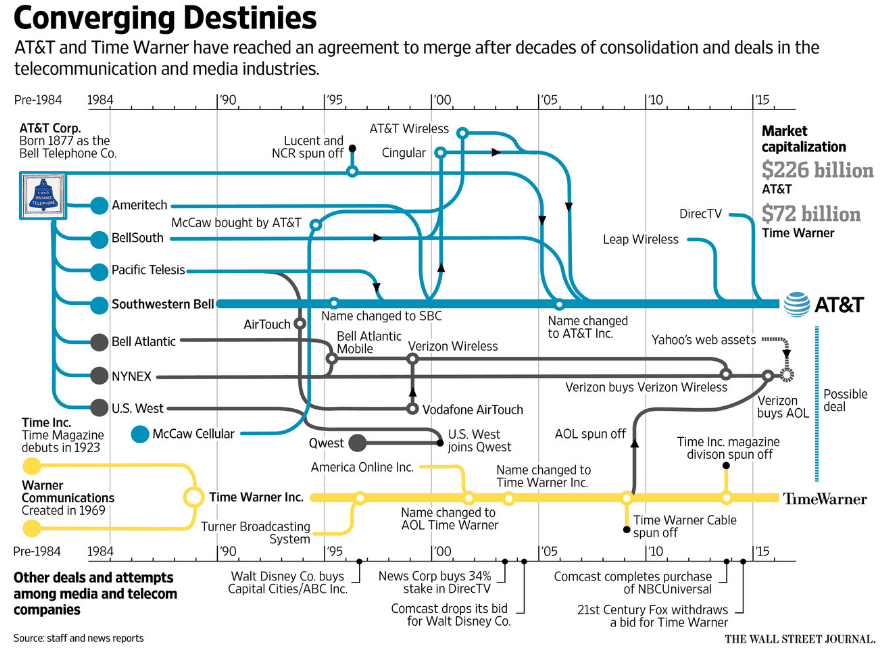

Last month one media behemoth, AT&T, stated it would purchase another, Time Warner, for $85.4 million. AT&T provides a telecommunications service, while Time Warner provides content. The merger represents just one more step in decades of media consolidation, the placing of control over media and media provision into fewer and fewer hands. This graphic, from the Wall Street Journal, illustrates the history of mergers for the latest companies to propose a merger:

The purchase raises several issues regarding consumer protections – particularly over privacy, competition, price hikes, and monopoly power in certain markets – and one of these is related to race.

A third of the American population identifies as Latino, African American, Asian American, and Native American, yet members of these groups own only 5% of television stations and 7% of radio stations. Large-scale mergers like the proposed one between AT&T and Time Warner exacerbate this exclusion. Minority-owned media companies tend to be smaller and mergers make it even harder to compete with larger and larger media conglomerates. As a result, minority-owned companies close or are sold and the barriers to entry get raised as well. The research is clear: media consolidation is bad for media diversity.

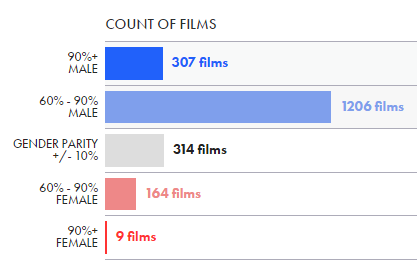

After the #OscarsSoWhite controversy, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences committed to increasing diversity on screen and technology companies have vowed to increase their workforce diversity, but such commitments have done relatively little to improve representation. Such “gentlemen’s agreements” are largely voluntary and are mostly false promises for communities of color.

Advocacy groups and federal authorities should not rely on Memorandum of Understandings to advance inclusion goals. When the AT&T/Time Warner deal gets to the Federal Communications Commission, scrutiny in the name of “public interest” should include the issue of minorities’ inclusion in both the media and technology industries. As a diverse nation struggling with ongoing racial injustices, leaving underrepresented communities out of media merger debates is a disservice not only to those communities, but to us all.

Jason A. Smith is a PhD candidate in the Public Sociology program at George Mason University. His research focuses on race and the media. He recently co-edited the book Race and Contention in Twenty-first Century U.S. Media (Routledge, 2016). He tweets occasionally.

Pre-prepared frozen meals pre-dated the Swanson “TV dinner,” but it was Swanson who brought the aluminum tray — previously only seen in taverns and airplanes — into the home.

Pre-prepared frozen meals pre-dated the Swanson “TV dinner,” but it was Swanson who brought the aluminum tray — previously only seen in taverns and airplanes — into the home.