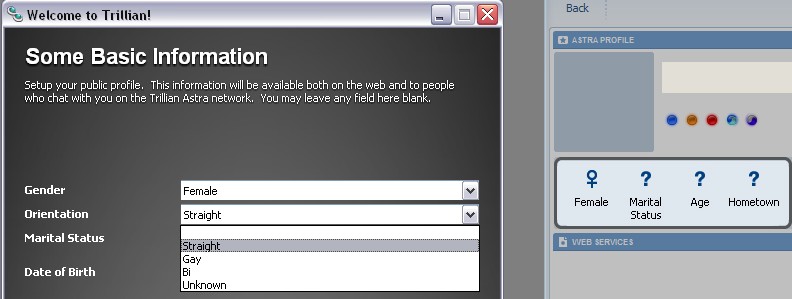

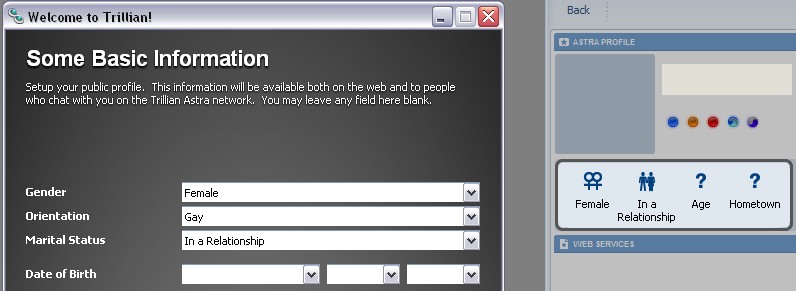

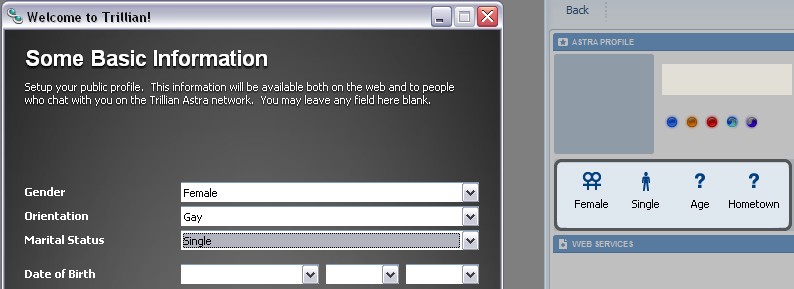

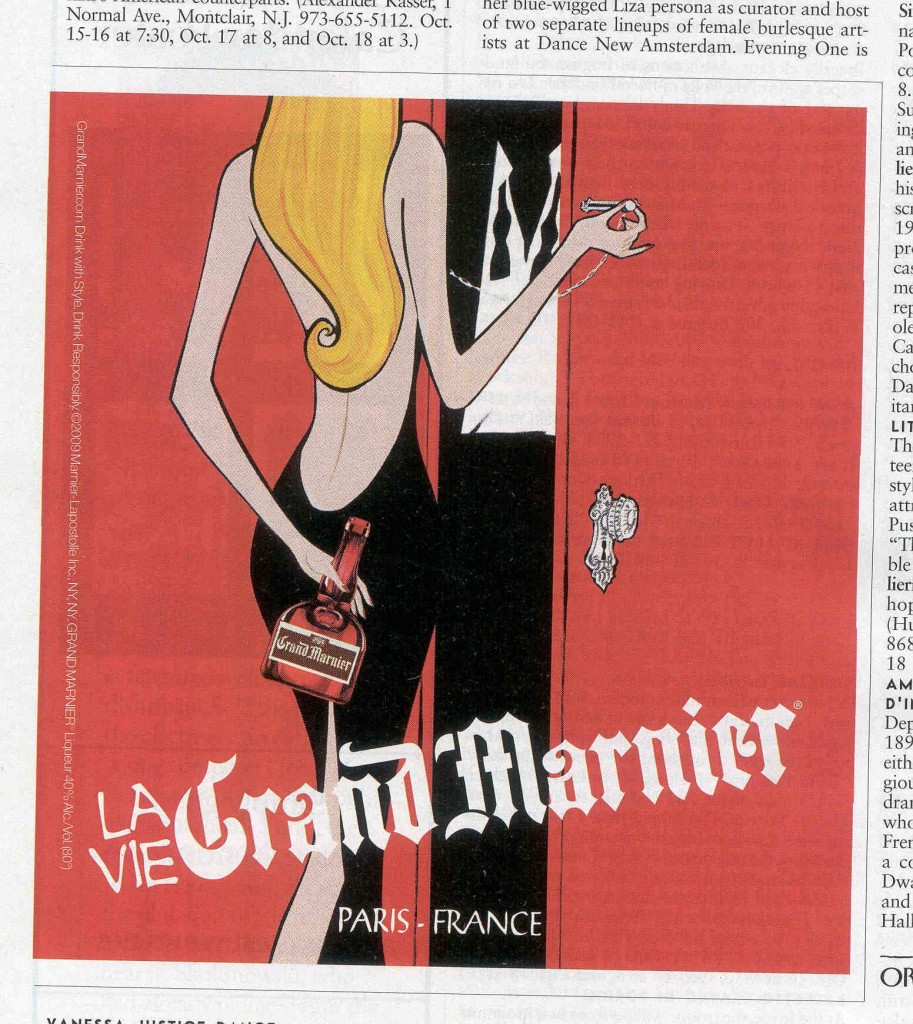

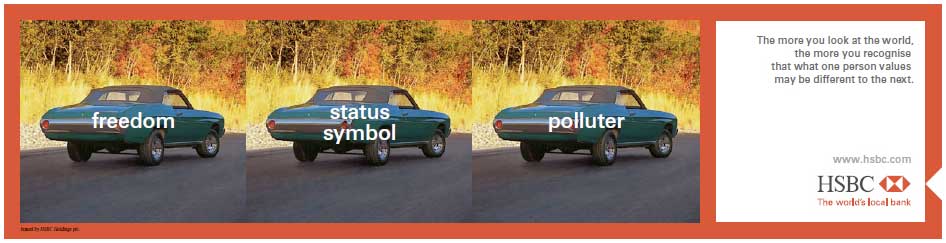

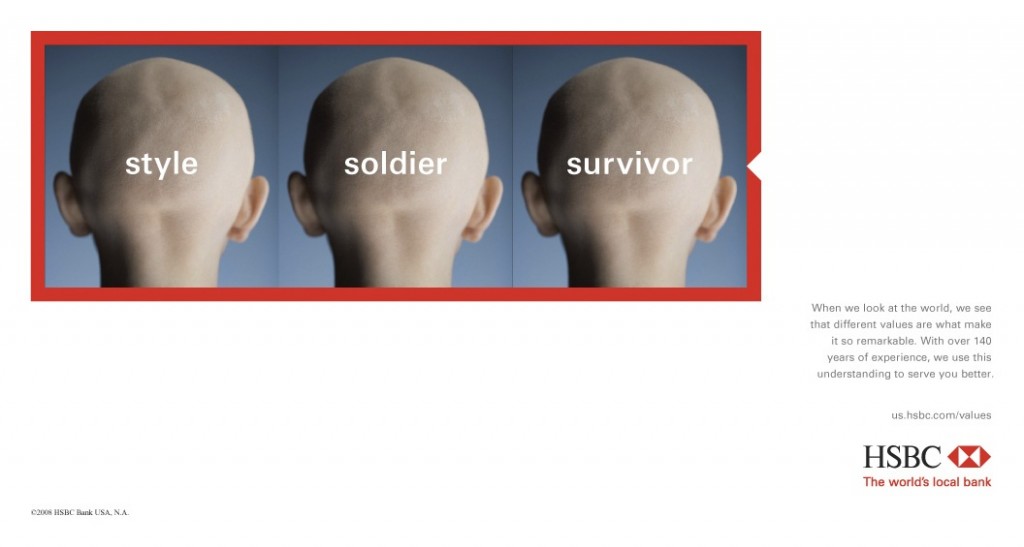

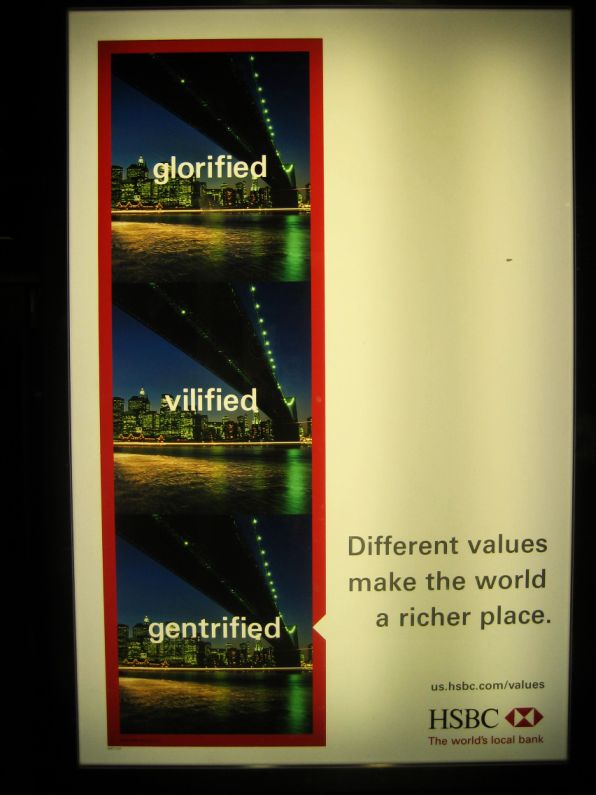

Jay Livingston, who blogs at MontClair SocioBlog, put up a set of ads for a bank that illustrate a basic sociological insight. The message in the ads is “Different values make the world a richer place” and they each feature the same image triply labeled.

Privilege. Sacrifice. Role model.

Decor. Souvenir. Place of prayer.

Freedom. Status symbol. Polluter.

Style. Soldier. Survivor.

Glorified. Vilified. Gentrified.

They say that a photograph is worth a thousand words, but this exercise reminds us how much words, even one word, can shape our interpretation of an image. The world doesn’t just exist, it must always be interpreted. Those immediately around us have a great ability to influence how we see the world, but the people with power over media do also… and their power is vast.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.