Flashback Friday.

How do people in the U.S. become wealthy? According to the myth of meritocracy, they do so by hard work: blood, sweat, tears, a trace of talent, and a tad bit of luck. This is the story told in this two-page ad for U.S. Trust in The New Yorker:

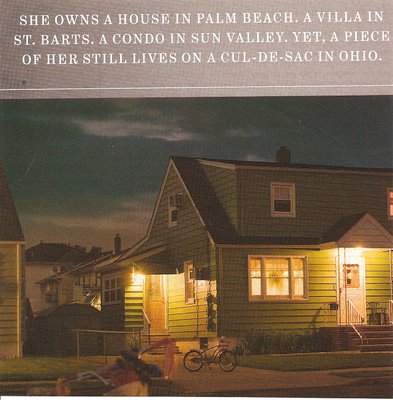

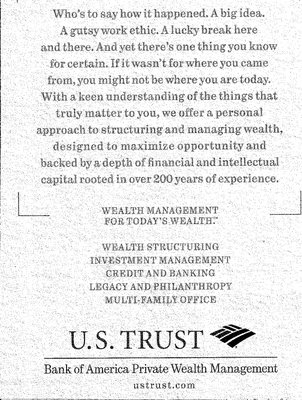

On the first page we learn she’s rich, but she’s still a home-town girl at heart. On the second page, we learn a little about how she might have gotten so wealthy:

Note the first few sentences:

Who’s to say how it happened. A big idea. A gutsy work ethic. A lucky break here and there.

Well, uh…what about, “She inherited it”? That’s a pretty common way to end up with a whole bunch of houses and in need of a wealth management team.

The notion that rich people are rich because their parents are rich, however, interrupts the American mystique, the one where we are a country of self-made immigrants who pulled ourselves up by our bootstraps. People, even people who inherited wealth, like to think that they’re rich because they worked hard. Hence, the romanticization of the self-made millionaire in the ad and the corresponding invisibility of the inheritance loophole.

On the flipside, this narrative also supports the converse idea that the poor are poor because of their lack of personal efforts and merits. Perhaps they didn’t have a “big idea’ or the “gutsy work ethic” that enabled them to profit from the lucky break that they inevitably encountered, right?

This ad is just one drop in the sea of propaganda that makes it seem right and normal that a small proportion of our population is able to hoard wealth and property.

This post originally appeared in 2008.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.