Recently, Raz sent in this image of cans of WD-40, part of their Collectible Military Series, for sale at an auto parts store:

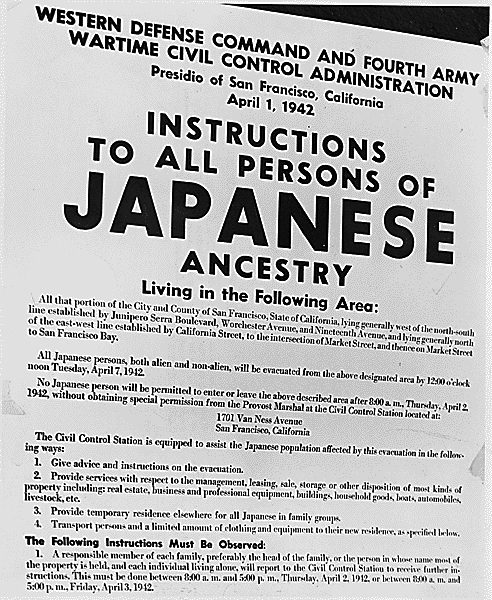

The types of war-related advertising we see can give us insights about how average Americans are connected to, and affected by, different wars. During many U.S. wars, contributing to the war effort was the duty of every citizen; this is particularly apparent with World War II. The draft, the deployment of some 16 million Americans, and public calls to purchase war bonds and ration food meant that war was nearly everyone’s concern. In contrast, the current War on Terrorism mostly only impacts those connected directly to it—military families. There are no widespread calls to ration, buy war bonds, or otherwise support the war effort through employment, growing vegetables, saving scrap metal, or other changes to our daily lives. My own research shows that members of military families feel the war is ignored and forgotten by most Americans. They feel isolated in their daily anxieties and their efforts to support their loved ones.

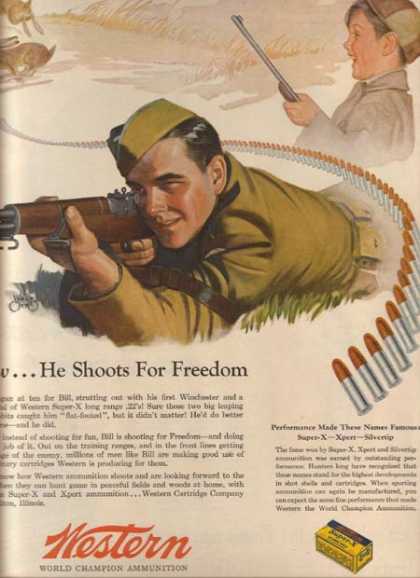

Products like the WD-40 Collectible Military Series were more common during WWII than they are now. During WWII advertising used the war cause and feelings of patriotism to sell a wide range of products that, ads argued, would help the U.S. win. Some were clearly connected to the war effort:

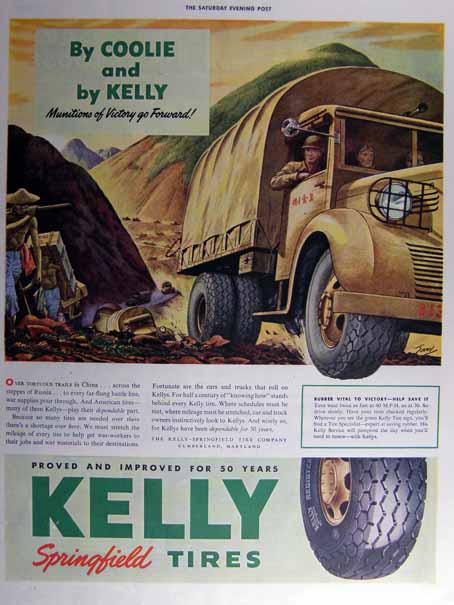

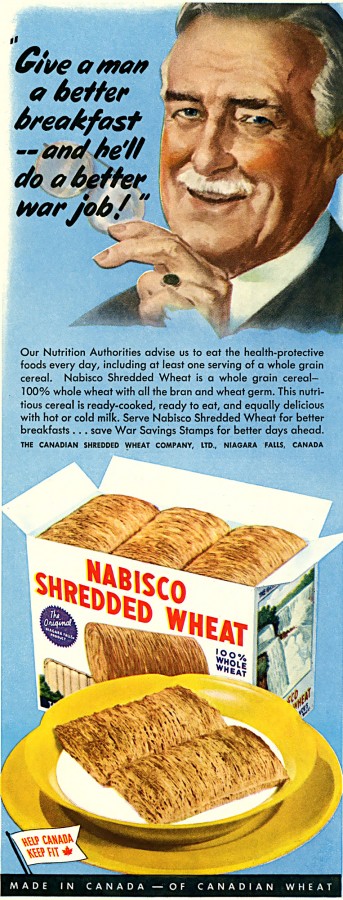

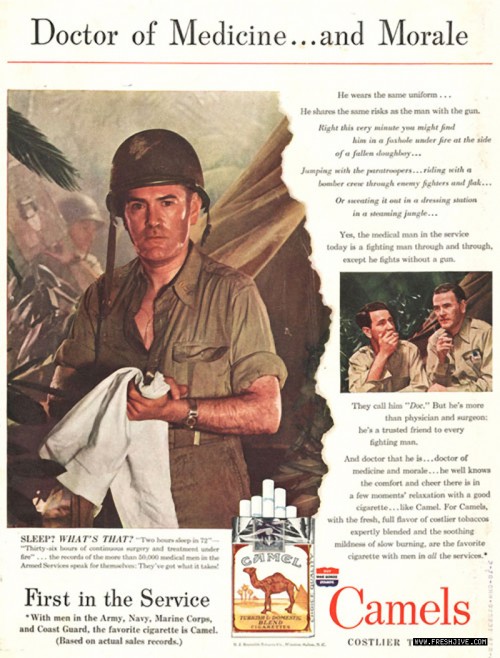

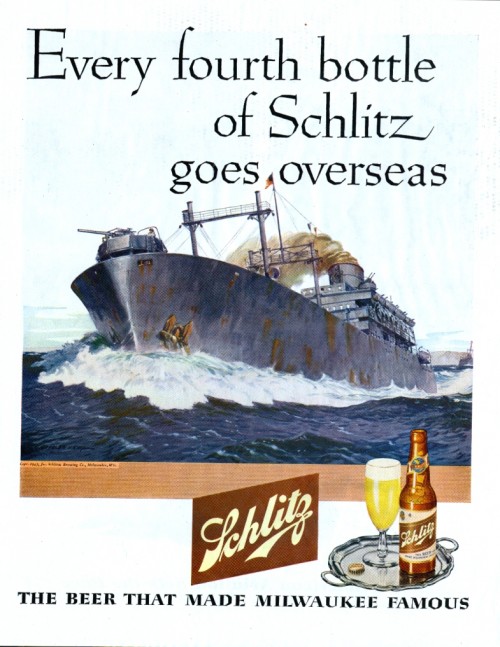

With others, the connection was much less obvious or direct:

Both Shlitz and Camel donated to the war effort. Similarly, with their “Drop and Give Me 40” campaign, WD-40 is donating part of their profits to charities that support service members and their families:

For each can purchased from March 2011 through May 2011, WD-40 Company donated 10 cents to three charities that help active-duty military, wounded warriors, retired veterans and their families. On Memorial Day, WD-40 Company presented $100,000 checks to each of the following military charities: Armed Services YMCA, Wounded Warrior Project, and the Veterans Medical Research Foundation.

Although military-themed products (aside from “support the troops” t-shirts, stickers and pins that are widely available) are not as common as they were during WWII, some companies have come out with patriotic advertising.

Goodyear has “support the troops” tires, sold and marketed at NASCAR races:

An Anheuser-Busch commercial shows ordinary Americans stopping their everyday lives to thank the troops. There is no mention of the company until the very end, and nothing at all about beer:

American Airlines has a similar advertisement depicting various Americans being supportive the troops before and during their flight:

The messages in these recent ads are markedly different than the WWII messages of everyone taking part and working toward victory, reflecting changing relationships between war efforts and the average citizen. No reminder of the war was necessary in the 1940s—war was a part of everyday Americans’ lives. Current ads, like the WD-40 series, often serve less as a call to specific action than as a reminder that the war exists, as a reminder to thank the troops and support service members. It’s a different type of message for a different type of war, one that only involves a small fraction of Americans and is often largely invisible to everyone else.