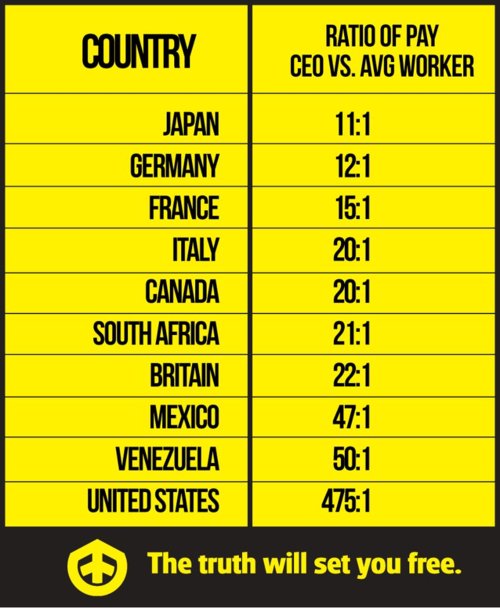

UPDATE: Since posting this, I’ve discovered that the numbers do not accurately reflect the ratio of CEO vs. worker pay. Writes PolitiFact:

We don’t doubt the chart’s underlying point that the ratio of CEO pay to worker pay is high in the United States, and is likely higher in our free-wheeling economy than it is in the historically more egalitarian nations of Europe.

But in its claim that the U.S. ratio is 475 to 1, the chart conveys a sense of certitude and statistical precision that simply isn’t warranted — and which is contradicted by the facts. The latest number for the U.S. is 185 to 1 in one study and 325 to 1 in another [though in previous years, those ratios have reached as high as 525 to 1] — and those numbers were not generated by groups that might have an ideological interest in downplaying the gaps between rich and poor. We rate the claim on the U.S. ratio False.

I apologize for not vetting this more carefully.

H/T KeepYourHopesUpHigh via GlobalSociologyBlog.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.