Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

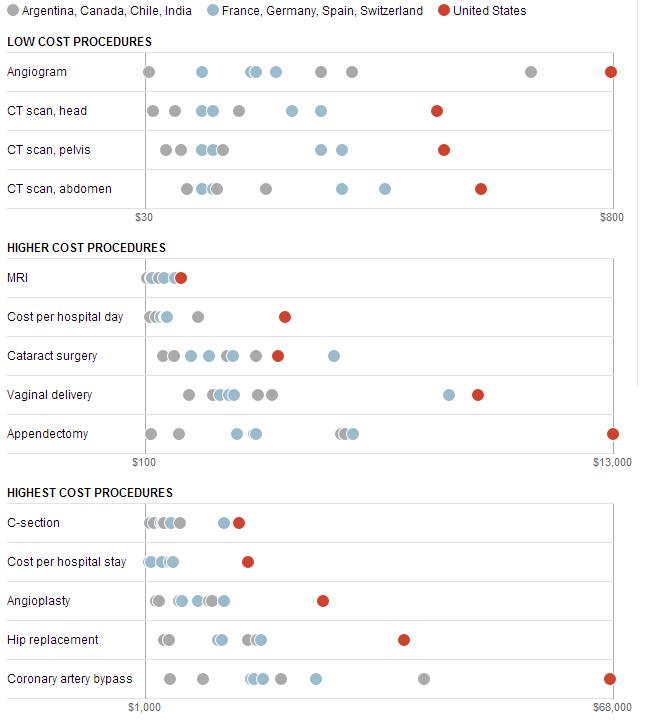

The Washington Post has provided some data on medical costs across a selection of countries (Argentina, Canada, Chile, and India in grey; France, Germany, Switzerland, and Spain in blue; and the U.S. in red). The data reveal that American health care is very expensive compared to other countries.

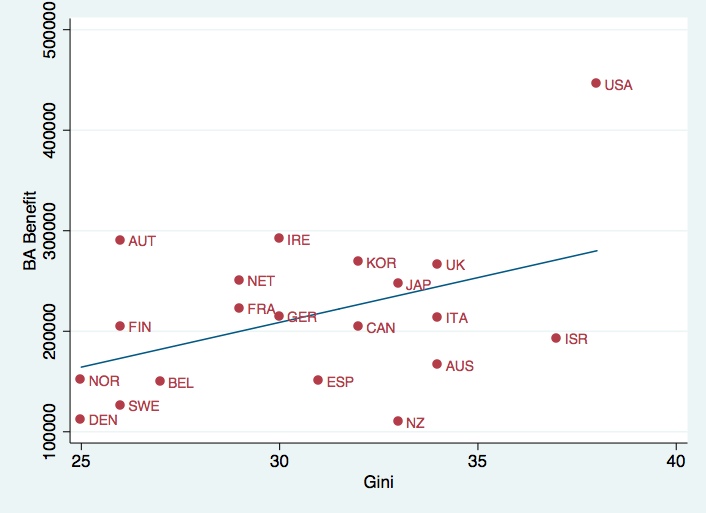

No wonder the US spends twice as much as France on health care. In 2009, the U.S. average was $8000 per person; in France, $4000. (Canada came in at $4800). Why do we spend so much? Ezra Klein quotes the title of a 2003 paper by four health-care economists: “it’s the prices, stupid.”

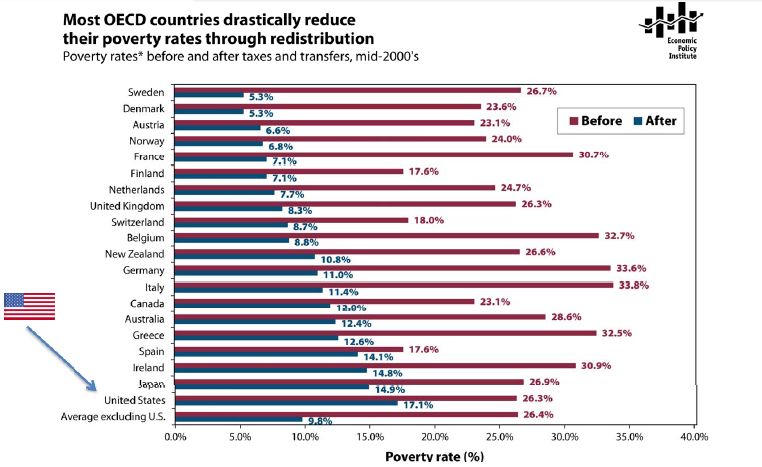

And why are US prices higher? Prices in the other OECD countries are lower partly because of what U.S. conservatives would call socialism – the active participation of the government. In the U.K. and Canada, the government sets prices. In other countries, the government uses its Wal-Mart-like power as a huge buyer to negotiate lower prices from providers. (If it’s a good thing for Wal-Mart to bring lower prices for people who need to buy clothes, why is it a bad thing for the government to bring lower prices to people who need to buy, say, an appendectomy? I could never figure that out.)

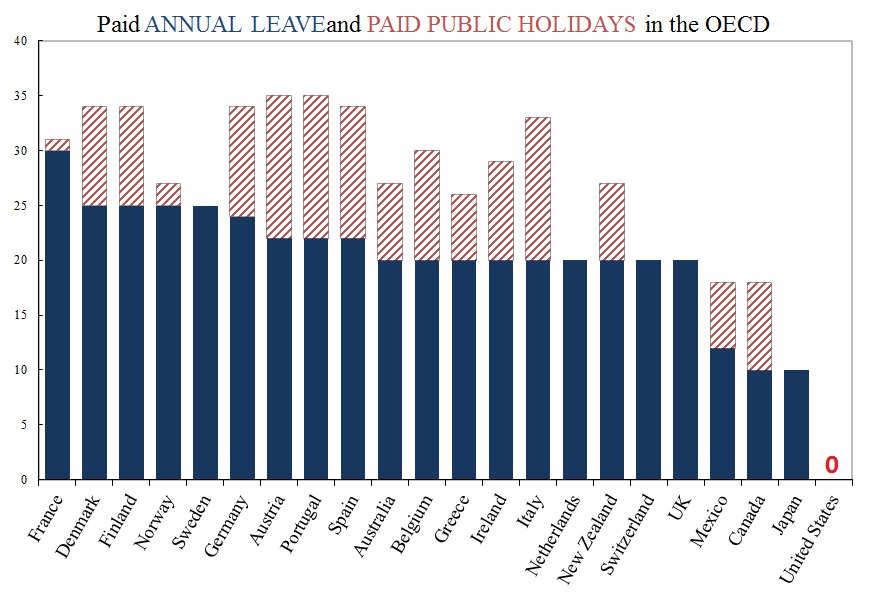

There may also be cultural differences between the U.S. and other wealthy countries, differences about whether greed, for lack of a better word, is good. How much greed is good, and in what realms is it good? Klein quotes a man who served in the Thatcher government:

Health is a business in the United States in quite a different way than it is elsewhere. It’s very much something people make money out of. There isn’t too much embarrassment about that compared to Europe and elsewhere.

So we Americans roll along, paying several times what others pay for medical procedures, doctor visits, and drugs.

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.