Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

According to an op-ed in the Times, America is the global leader in broadband, with high speeds and great service. And it’s all because the government restrained “onerous” regulation and let companies like Verizon do what they want and charge what they want.

It was written by the CEO of Verizon, Lowell McAdam.

I pay Mr. McAdam’s company about $115 each month for my land line, wi-fi, and cable (all FIOS). Mr. McAdam compares the U.S. favorably with Europe, “where innovation and investment in advanced networks have stagnated under an onerous regulatory regime.” I asked a friend who lives in Paris what he pays for his FIOS phone, wi-fi, and cable. The monthly bill: 39.90€ ($52) or half of what I pay Verizon. Maybe there’s an upside to stagnant and onerous.

There’s nothing wrong with getting what you can afford, and it occurred to me that U.S. broadband is the best because we can afford more. Onerous regulations or no, most other countries are not as rich as the U.S. What if you looked at broadband and per capita GDP?

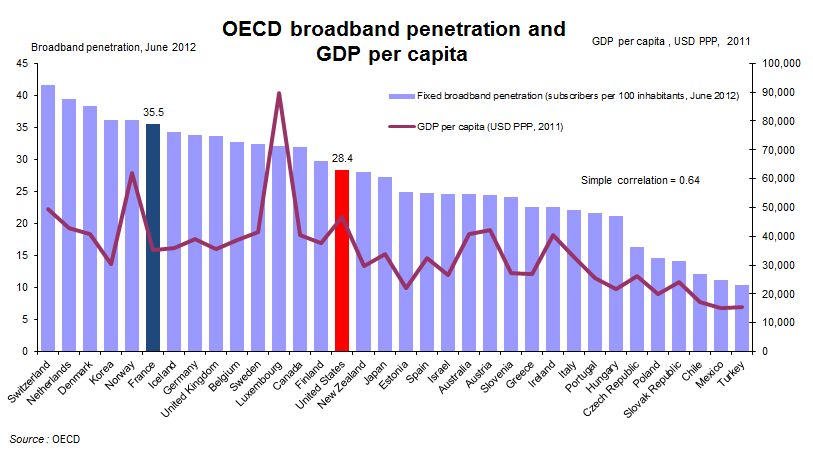

The OECD did just that with data from June 2012 (their several spreadsheets on this are here). The purple bars are broadband penetration and the bumpy red line is GDP per capita. Do you see a correlation?

Consider France: As of a year ago, the country had greater broadband penetration despite a lower per capita GDP than the U.S. ($35,133 vs. $46,588); that’s 25% more broadband on 33% less income and at half the cost to consumers.

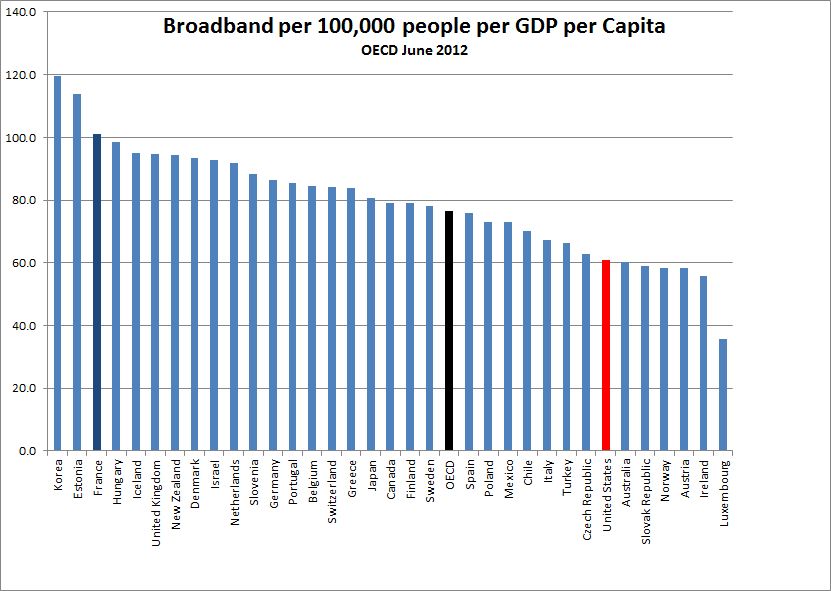

If you re-rank the OECD countries factoring in per capita GDP, the line-up changes. Notably, the U.S. and Luxembourg drop well below the OECD average, despite being among the wealthiest countries.

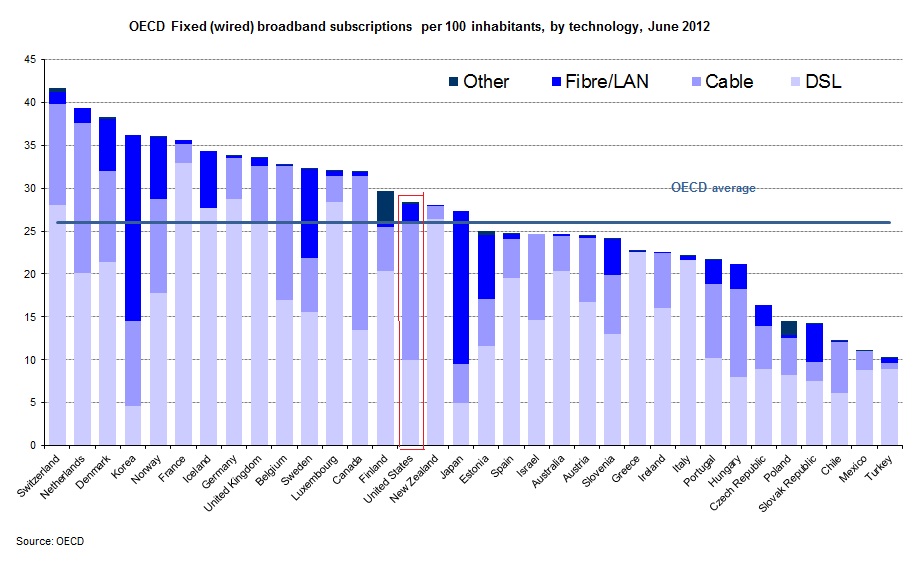

Of course, not all broadbands are equally broad. Verizon sold me on fiber-optic with their assurance that it was dazzlingly faster than their DSL that I had been clunking along on. This graph breaks down broadband into its various incarnations.

The U.S. is slightly above average on all broadband, but when it comes to a high fibre diet, we are ahead of several other countries that have greater total penetration. On the other hand, the Scandinavian countries are ahead of us, as are, impressively, the Asian countries.

This is not to deny U.S. advances. TechCrunch summarizes more recent data from Akamai on these changes:

the U.S. is currently second in the price of broadband for entry-level users. The nation is also third in network-based competition, second in the fiber-optic installation rate, first in the adoption of next-generation LTE, ahead of Europe in broadband adoption, and doing quite well in Internet-based services.

Still, the U.S. lags behind other, less wealthy countries. InnovationFiles, using Akamai data for different variables, has a less congratulatory view.

- The U. S. has picked up one place in the “Average Peak Connection Speed” that’s the best measurement of network capacity, rising from 14th to 13th as the measured peak connection speed increased from 29.6 Mbps to 31.5 Mbps.

- In terms of the “Average Connection Speed,” widely cited by analysts who don’t know what it means, the U. S. remains in 8th place world-wide. but we’re no longer tied for it as we were in the previous quarter; Sweden is right behind us on this one.

- In terms of “High Speed Broadband Adoption”, the proportion of IP addresses with an Average Connection Speed greater than 10 Mbps, we remain in 7th place, but now we’re tied with Sweden.

The title of CEO McAdam’s op-ed is “How the US Got Broadband Right.” Given the content, I guess “We’re Number 13!” wouldn’t have been appropriate. Even “We’re Number Seven (Tied With Socialist Sweden)!” doesn’t quite have that affirmative zing.

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.