The United States is a nation of immigrants… in that the majority of its citizens are not part of the native population of North America. In other words, because it was and remains a colonized land.

That aside, is the United States unique in receiving an extremely large number of new immigrants relative to its size? It turns out, No.

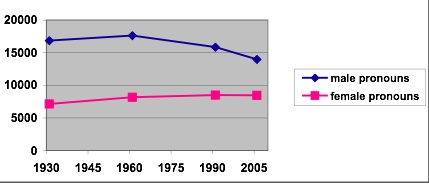

Lane Kenworthy, at Consider the Evidence, posted this figure, showing that the U.S. population does indeed include a substantial proportion of first generation immigrants (both legal and illegal), but it is not unique in that regard, nor does it carry the highest percentage:

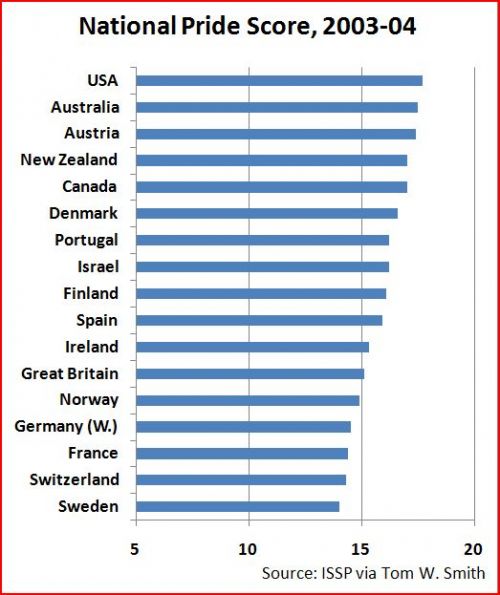

It also fails to be true, as many anti-immigration people claim, that the U.S. accepts a uniquely large number of immigrants who need help once they arrive:

It also fails to be true, as many anti-immigration people claim, that the U.S. accepts a uniquely large number of immigrants who need help once they arrive:

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.