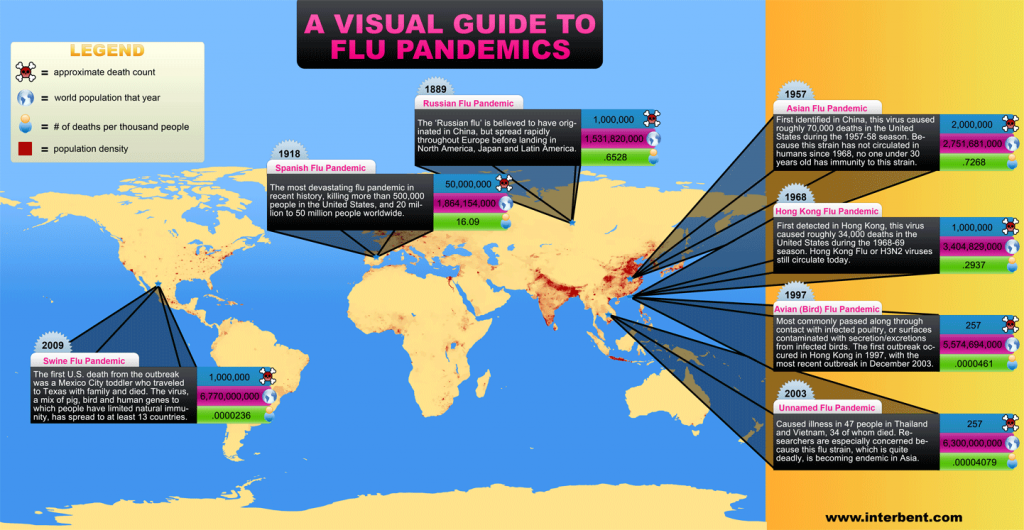

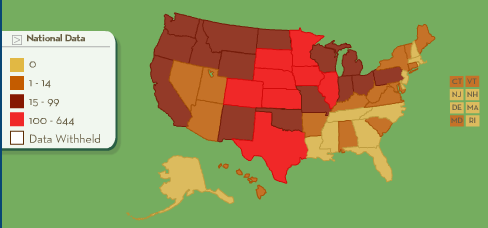

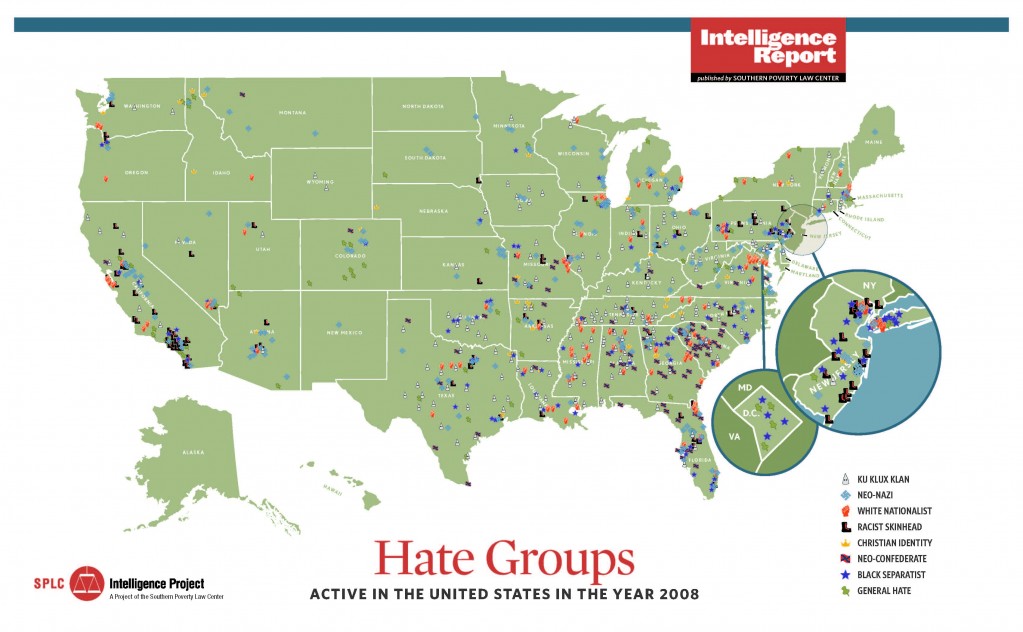

Emily K. sent in a link to the Southern Poverty Law Center’s 2009 report on hate groups in the U.S. Here’s a map (larger, not-stretched-out version available as a pdf here):

The site also has an interactive map where you can select individual states and get more info on the hate groups that are active there, and another where “hate incidents” are marked.

Sorry for the sporadic posting lately–it’s the last week of the semester and I’m grading constantly.

UPDATE: One of my best friends just informed me that when investigating the SPLC hate incidents map, he realized he knew one of the people listed as a perpetrator in an incident in a certain Southern state; I promised to give no more details than that. This led to a discussion of the weirdness of some of the folks we grew up with, including a guy I went to school with who washed his head in gasoline to try to kill lice and ended up setting his entire head on fire. And no, I don’t know why a person would decide to use gasoline to kill lice. I also don’t know how one of my uncles managed to shoot himself in the foot while elk hunting, why that didn’t deter another uncle from going, falling down a mountain slope, and cracking his ribs, or why my mom married an evangelical Christian who didn’t like women to wear pants eight weeks after she met him on the internet. These are some of the many mysteries of life.

ANOTHER UPDATE: Commenter OP Minded says,

Kind of outrageous that the SPLC has “Concerned Citizens and Friends of Illegal Immigration Law Enforcement” in Framingham, MA listed as a hate group. There is no doubt that they are in favor of enforcing immigration law (after all, it is the law) but they don’t fall anywhere near a “hate group”. Calls into question this entire list.

Another commenter says,

To follow up on opminded@2: It’s too bad the Southern Poverty Law Center also uses these trumped-up threats to pad its already-deep coffers. Less than 70 percent of its expenses go toward its programs; the rest is for administration and fundraising. Any human rights organization with almost $220 million in net assets isn’t doing its job.

The anonymous commenter suggests going to Charity Navigator to get more information.

I did not know about these criticisms (a problem in general about charities is not knowing for sure how the money is spent). My experience with the SPLC relates to their work with African American farmers in the South, a group that has experienced major land loss due to various factors largely involving racism and unscrupulous land developers. Their work on that particular issue was considered pretty solid. But of course there aren’t all that many organizations working on that problem, so any efforts were greatly appreciated.

Thanks for the additional info!

ANOTHER UPDATE: Commenter CLL says,

Over the years, SPLC has done terrific work helping people with little access to power receive the justice they deserve. Groups the SPLC has identified as “hate” groups have gone beyond simply disagreeing with policy (or lack of enforcement), and have instead encouraged their adherents to express discontent in more direct attacks on the object(s) of their scorn — thus qualifying as “hate” groups.

Spending 69.6% of income on programs remains a pretty normal ratio for not-for-profits that rely heavily on professional staff. Some organizations play fast and loose with their Fundraising allocations to cook the percentages down to numbers that look better on sites like Charity Navigator — but the proof of effectiveness is in accomplishment of mission.