The representation of sexuality and safer sex in public health campaigns is fascinating given our simultaneous cultural obsession with yet pathologization of sexual behavior. Safer sex campaigns and materials not only seek to increase prevention behaviors but also produce a range of social meanings surrounding gender, bodies, and desire. Most are produced by organizations that fall well within the mainstream; others are not. This post is about one of the latter (warning: sexual explicitness).

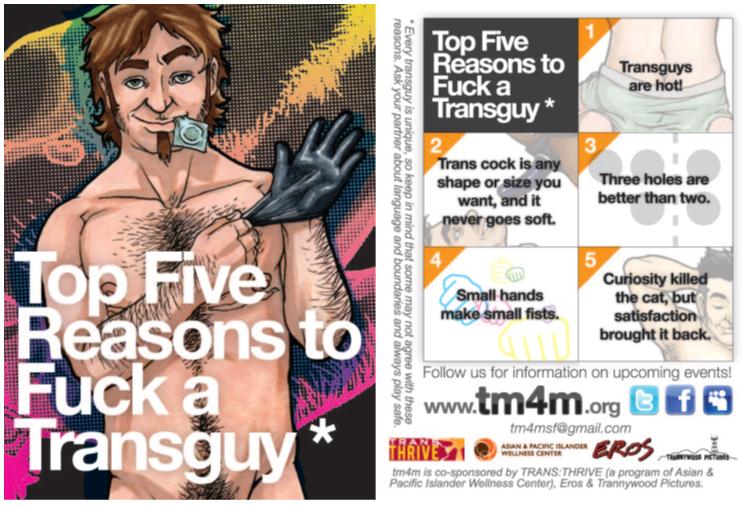

The following resource, titled “Top 5 Reasons to Fuck a Transguy” was produced and distributed by a collaborative project of the San Francisco-based Asian and Pacific Islander Wellness Center. tm4m is a group for transgender men whose goal is to “provide information, education and support to transmen who have sex with men (both other transguys and cisguys).”

This material is interesting for two main reasons. First, it combines traditional health education with an erotic, sex-positive context that is missing from most public health campaigns. For the most part, public health approaches to HIV prevention and sexual health promotion utilize a “sex-negative” approach to sexual behavior; in other words, sex is represented as potentially dangerous or problematic and focus narrowly focused on its negative aspects, such as disease transmission. Even more progressive “comprehensive” approaches to sexual health education (that is, approaches that do not focus solely on abstinence) tend to center on the potentially dangerous outcomes of sex and how to prevent them while ignoring the pleasurable and fun aspects of sexuality.

In contrast, “5 Reasons to Fuck a Transguy” depicts a naked transman with safer sex barriers (condom and a glove) and uses explicit language (“fuck” instead of “sex” and “cock” instead of “penis”) and imagery. For example, in reason #2 we see two people about to engage in strap-on play and in #5 we see a guy that appears to be receiving oral sex or relaxing in a state of post-sex ecstasy. This sort of language and imagery is absent from the vast majority of sexual health promotion materials aimed at a wide variety of populations. Thus, in “5 Reasons to Fuck a Transguy,” safer sex is not presented as distinct and separate from sexual pleasure.

Second, the material uses an embodied approach to highlight differences between trans and cisgender men while at the same time eroticizing that difference. Starting with reason #1 (“trans guys are hot”) we are invited to see the transmale body as the object of desire. Reasons #2, #3, and #4 call attention to the physical differences between cisgender and transgender male bodies and eroticizes the latter by emphasizing interchangeable cock sizes, more holes to penetrate, and smaller hands for fisting (or using the whole hand for penetration). Finally, reason #5 alludes to a fetishization of transmen: the transgender body incites curiosity that will ultimately pay off in enhanced pleasure.

Not everyone agrees this is good. Some posts on Tumblr challenged the idea that transgender men are a sort of erotic “other” or that they will necessarily consent to the activities depicted in the pamphlet:

You better not assume I’m comfortable using the one that “other” guys don’t have and you better not assume that being a guy means I’d be up for being fucked in the ass, either. Go fuck yourself and make your own goddamn third hole.

The “your dick can be any size you want!” argument is like telling a female-identified survivor of breast cancer who’s had a mastectomy “your tits can be any size you want!”

Just because I don’t have my own natural cock doesn’t make me this insane sex toy thing that’s such an anomaly and such a fetish object and so very very strange and different.

So, despite the disclaimer that “every transguy is unique,” some viewers saw the material’s approach as a problemtic eroticization of their bodies and gender.

In sum, “5 Reasons to Fuck a Transguy” moves beyond typical sexual health promotion approaches to include desire and pleasure, but doesn’t avoid the problem of sending its own cultural messages about gender, bodies, and desire, ones that may be problematic from an entirely different point of view.

Christie Barcelos is a doctoral candidate in Public Health/Community Health Education at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.