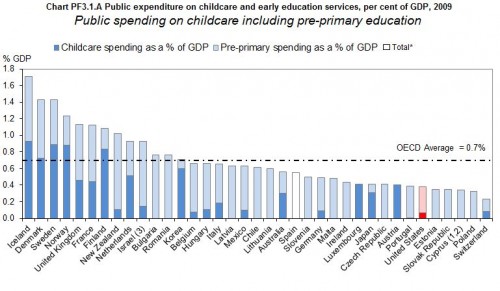

In this 15min TED talk, the eminent masculinities scholar Michael Kimmel argues that feminism is in everyone’s best interest. After discussing the robust research on the benefits of gender equality, he concludes:

Gender equality is in the interest of countries, of companies, and of men, and their children and their partners… [It is] is not a zero sum game, it’s not a win-lose, it is a win-win for everyone.

Watch!