The current political discourse is so focused on a single form of government revenue, that the word taxes has become essentially synonymous with just one tax in particular; the federal income tax. In fact, unless there is a foreign policy crisis, the federal income tax usually dominates most political discussion given how the federal budget (or increasingly the federal debt) relates to almost anything and everything the federal government does (or does not do in more and more instances).

For example, during the closing months of 2012 we watched how a fight over a sunset of the Bush Tax Cuts almost shoved the United States over a fiscal cliff. Just prior to this near crisis, the most discussed difference between 2012 presidential candidates was their disagreement about a 4 point increase in the highest federal income bracket. Also, Mitt Romney will likely be remembered mostly for his disparagement and disregard of “The 47% of United States Citizens who pay no federal income tax.”

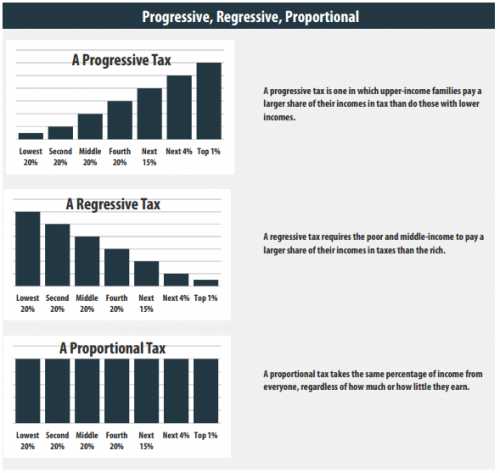

However, limiting discussion about government funding and spending to just the federal income tax and ignoring the other types of payments we make to the treasury is not without consequence, especially given how the federal income tax is actually a very unique kind of tax. Unlike excise taxes, payroll deductions, sales taxes and most property taxes that are regressive or require the poor to pay a larger proportion of their resources than the wealthy; the federal income tax is one of the few progressive taxes in the United States because at least on paper (I say that because these marginal rates often do not equate the larger effective rates given that the wealthy are afforded more loopholes, deductions, and lower rates on investment income), the rich pay larger marginal rates than the middle-class and poor. Thus, with our political discussion largely limited to the federal income tax, it should come as no surprise conservatives are so easily able to frame “The State,” especially the federal government, as a perverse Robin Hood who steals from the rich (the makers as they are being called now) to give to the poor (the takers).

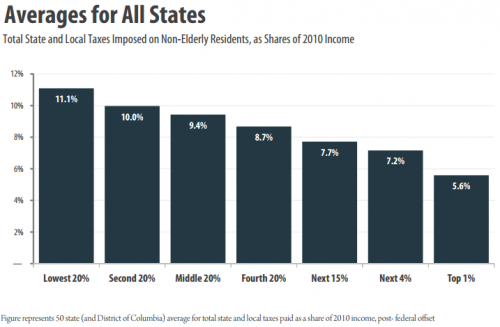

The non-profit, non-partisan Institution on Taxation and Economic Policy recently released its research on the taxes families in the United States paid in 2010. These findings reveal when the focus is taken off the federal income tax and the entire tax system is examined, cumulative household taxes in nearly every state are regressive because the less money a family makes, the larger proportion they pay to the different levels of government. As the graph below shows, the cumulative tax system is regressive because sales, excise and property taxes offset progressive income taxes at both the state, and federal levels.

The tax system as a whole is largely regressive because the higher one’s class standing, the lower the proportion of total taxes they pay. While the report provides great details in the variations across each state, the graph below shows that on average, the lowest 20% of earners pays an overall tax rate that is more than twice of what the top 1% of earners pay.

While many citizens perceive the U.S. tax code as inherently unfair because the wealthy have higher marginal rates on their federal income tax (the only one anyone ever seems to talk about); an examination of the entire system reveals the opposite as cumulatively, the poor pay a larger proportion of their income to local, state, and the federal governments.

—————————

Jason Eastman is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Coastal Carolina University who researches how culture and identity influence social inequalities.