NASA has posted a series of pairs of satellite images that show a range of changes around the world. They’re great for illustrating human-environment interactions; some of the changes are directly human-caused, while others, while others show the changing consequences of floods and fires as our settlement and agricultural patterns change.

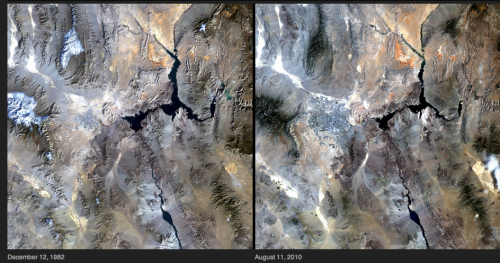

For those of us living in Las Vegas, these images of the shrinking Lake Mead reservoir, which provides water and electricity, is not reassuring. The reservoir has gotten smaller due to multiple factors, including a long-term drought and more water being taken from the Colorado River upstream:

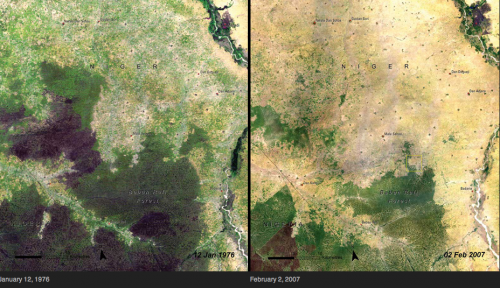

Deforestation in Niger, as land has increasingly been turned over to agriculture:

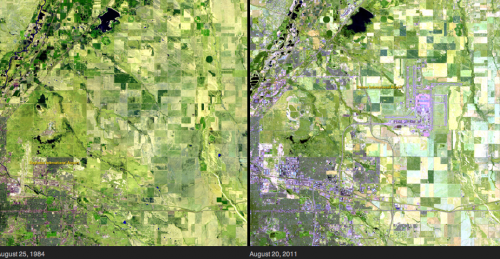

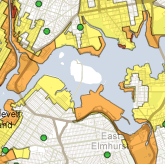

Here, we see increasing urban growth around Denver International Airport, which now takes up 53 square miles of what used to be farmland:

Algal blooms due to agricultural and household runoff into Lake Atitlan, Guatemala:

Changes to the Sonoran coastline in Mexico due to shrimp farming:

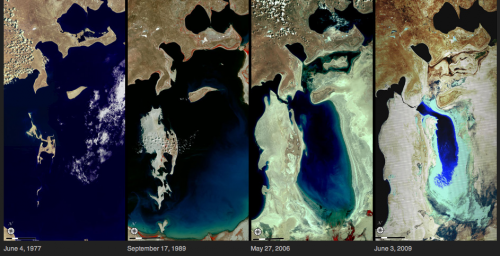

The dramatic shrinking of the Aral Sea, largely due to the amount of water taken out of rivers for irrigation:

The full set of 167 paired images is really striking, and if viewed in the “all images” layout, you can select among various topics, focusing on cities, water, human impacts, and so on.