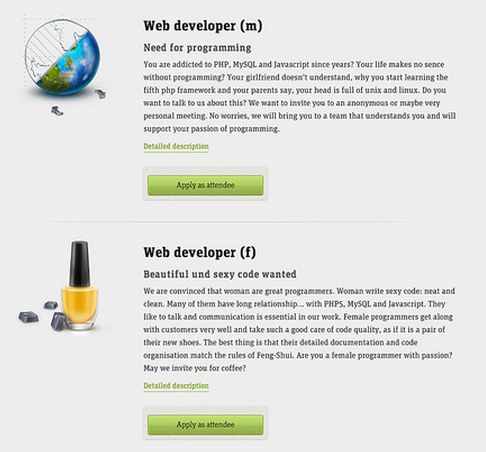

A blast from the past. Fred and Barney let their wives do all the work, pull out a pack of Winston’s:

Originally posted in 2008.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.