Count how many times the players wearing white pass the basketball, then continue after the jump:

biology

Women’s and men’s washrooms: we encounter them nearly every time we venture into public space. To many people the separation of the two, and the signs used to distinguish them, may seem innocuous and necessary. Trans people know that this is not the case, and that public battles have been waged over who is allowed to use which washroom. The segregation of public washrooms is one of the most basic ways that the male-female binary is upheld and reinforced.

As such, washroom signs are very telling of the way societies construct gender. They identify the male as the universal and the female as the variation. They express expectations of gender performance. And they conflate gender with sex.

I present here for your perusal, a typology and analysis of various washroom signs.

[Editor: After the jump because there are dozens of them… which is why Marissa’s post is so awesome…]

The phrase “nature/nurture debate” refers to an old competition between those who think that human behavior and psychology is determined by biology (that is, genetics, both evolutionary and individual, hormones, neurology, etc) and those who believe that it is determined by environment (that is, socialization, cultural context, experiences in childhood, etc). While the nature/nurture debate rages in the mass media, most scholars reject it altogether. Instead, social scientists and biologists alike recognize that our behavior and psychology is the result of an interaction between nature and nurture (yep, even sociologists like myself).

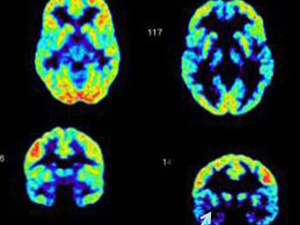

A recent story on NPR illustrates this beautifully. James Fallon, a neuroscientist specializing in sociopaths, had been scanning the brains of murderers for 20 years. His research had demonstrated that sociopath brains have a distinct appearance: dark patches in the orbital cortex, the part of the brain responsible for moral thinking and controlling impulses.

You can see the dark patches in the brain on the right, the brain on the left is a “normal” brain:

At a family gathering one day, Fallon’s mom mentions that there were some pretty violent types in Fallon’s own family history (it apparently didn’t come up anytime in the previous 20 years !!!) and, so, he investigates. It turns out that there were eight proven and alleged murders in his ancestral line, including Lizzy Borden, one of the most famous murderers in history. Because Fallon knows that the atypical neurology associated with sociopaths runs in families, he decided to scan the brains of all his family members. No one had the dark patches.

Except him. Fallon had the dark patches. In fact, that brain on the right: that’s him.

Not only did he have the neurology of a typical sociopath, he also carried a genetic determinant known to be associated with extreme violence.

Fallon doesn’t have the answer to why he’s not a sociopath, but scientists think that a person needs to have some sort of experiential trigger, like abuse as a child, in addition to a biological predisposition.

Significantly, [Fallon] says this journey through his brain has changed the way he thinks about nature and nurture. He once believed that genes and brain function could determine everything about us. But now he thinks his childhood [and his awesome mom] may have made all the difference.

For related examples, see our posts on the response of testosterone levels to political victories and the historical shift in the average age of menstruation.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

A blog post at Gallup, sent along by Michael Kimmel, discussed nearly 25 years of US opinion on the cause of homosexuality. The data shows a slow decline in the percent of people who think that people are “made” gay or lesbian by their upbringing or environment (the nurture argument) and a slow rise in the number of people who think they are “made” gay or lesbian by biology (the nature argument). The two meet in the late 1990s and, throughout the 2000s, they’ve been more-or-less neck-and-neck.

I welcome speculation as to why the trend didn’t continue such that nature ended up beating nurture good by 2010. I can’t think offhand of a reason why.

—————————

Lisa Wade is a professor of sociology at Occidental College. You can follow her on Twitter and Facebook.

The nature/nurture debate that posits a competition between biological and social/cultural influences on human behavior is alive and well in the mass media. But scholars largely agree that culture and biology interact; biological realities shape our social world, but our social world also shapes our biologies.

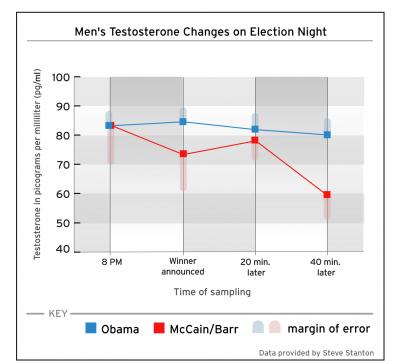

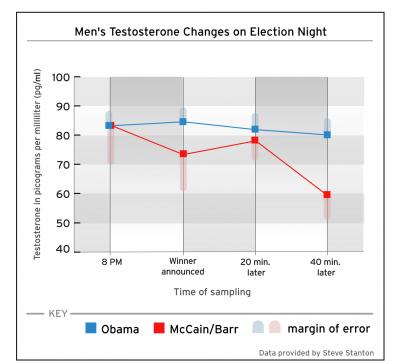

One strain of research demonstrating this has shown that men’s testosterone levels (associated with feelings of well-being) rise and drop in response to social (and socially constructed) cues. For example, the testosterone levels of the winner of a tennis match will rise after his win, while his opponent will see his levels go down. Similarly, measuring men’s testosterone levels won’t tell you which men walking down the sidewalk will enter a strip club, but the men leaving the strip club will have higher testosterone levels than the men who passed it by.

Matt C. alerted me to a test of this phenomenon using the Presidential election. There was a slight drop in testosterone levels for men who voted for Obama (normal because men’s testosterone levels tend to drop at night), but a dramatic drop for men who voted for McCain or the Libertarian candidate, Barr.

So, there you have it, biological responses to social cues.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Adeste S. sent in this performance by two women about the difficulties and frustrations of being transgendered:

Performed at Brave New Voices.

NEW! (Mar. ’10): Ryan sent in this video of Sass Rogando Sasot speaking to the United Nations about transgender rights. From an article at Coilhouse:

Her speech, titled “Reclaiming the Lucidity of Our Hearts”, addresses the need for vastly improved acceptance, support and protection of transgender citizens worldwide.

Her entire presentation is very moving, but about 8 minutes into this clip, something shifts in Sasot’s voice and delivery. What began as an engaging speech swiftly transforms into something far more urgent, immediate, and beautiful.

We posted earlier about the biology behind the controversy over Caster Semenya’s sex. Germán I. R.-E. and Philip Cohen (who has his own post on the topic) asked that we comment on her recent makeover.

Some sociologists argue that gender (as opposed to sex) is really more about performance than it is about our bodies. That is, we do gender and, when we do it in ways that other people recognize, everyone feels satisfied. This is, perhaps, what Caster Semenya’s handlers were hoping for when she submitted to a makeover for South Africa’s YOU Magazine:

Notice that Semenya carries the same body into this photoshoot, but she is properly adorned with make up, feminine clothing, jewelry, a passive pose, and a pleasant and inviting facial expression (because to be feminine is to be accommodating).

Perhaps more importantly, the copy and the interview tells the reader that Semenya likes dressing up and looking pretty, another important indicator of both femininity and non-masculinity. The cover says:

WE TURN SA’S POWER GIRL INTO A GLAMOUR GIRL – AND SHE LOVES IT!

(Notice, too, the implication that power and glamour are opposed.)

This insistence that Semenya feels (or wants to feel) feminine, as well as looks it, is mirrored in the text (as summarized by the Guardian):

It carries an interview with the 18-year-old student. “I’d like to dress up more often and wear dresses but I never get the chance,” she says. “I’d also like to learn to do my own makeup.”

The lifestyle magazine quotes Semenya’s university friends saying that she wants to buy stilettos and have a manicure and pedicure. Semenya adds: “I’ve never bought my own clothes – my mum buys them for me. But now that I know what I can look like, I’d like to dress like this more often.”

You magazine says that, after the photoshoot, Semenya told her manager that she would like to buy all the outfits she had modelled.

So, in the face of the leaked and unconfirmed finding that Semenya has undescended testicles and higher levels of testosterone than the “average” woman (see note at end*), there is an assertion here that what matters (i.e., the measure of sex that we should attend to) is her gender identity (feeling feminine) and her gender performance (doing femininity).

Anna N. at Jezebel points to how the public interest in Semenya’s sex may have pressured her, and those around her, to play this gender game. She writes:

…up until now, Semenya and her family have been unapologetic about the way she looks and dresses. Her father said that she had always preferred pants, but that she was still a woman — and the idea that she has to put on a dress and lipstick to prove her femaleness to people is pretty depressing.

It is also something that almost all women in Western countries do everyday. We perform gender, in part out of habit and in part consciously, all the time. Semenya hasn’t cared about this performance and that is at least in part why the controversy over her sex is taking the form that it is.

* Note: The release of male-related hormones, androgens, isn’t the whole story here. Cells must also have the relevant receptors for the presence of the hormones to matter. Semenya likely is lacking some of those receptors, either in her whole body on in parts of her body, because her body obviously didn’t respond to the hormones (otherwise she would have a penis and scrotum). My point here is dual: (1) the presence of testicles and testosterone doesn’t tell the whole story and (2) even if we knew the whole story, it doesn’t tell us if she is female or male. What if her body doesn’t detect the presence of those androgens? What if it reads the presence of some of them, but not others? What if she is chimera or mosaic? All these are interesting questions biologically, but the answers will not tell us whether she is male or female because sex, like gender, is a social construction.

—————————

Lisa Wade is a professor of sociology at Occidental College. You can follow her on Twitter and Facebook.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

I saw this footage of flatworm reproduction years ago on PBS and I was so excited when Robin H. sent it in!

Flatworms are hermaphroditic. All flatworms can inseminate and be inseminated. These flatworms also have two penises each. Flatworms are sexual. That is, they reproduce sexually by finding a partner with which to trade genetic material. (Asexual creatures do not trade genetic material, they reproduce by making copies of themselves.)

A flatworm reveals its two penises (in white):

What is interesting about this clip sociologically (in case you’re not already intrigued enough) is how the narrator describes what the flatworms are doing.

Let’s first suppose that it makes little sense to attribute human emotions and motivations to flatworms. Let’s also suppose that narrations of animal behavior are often going to tell us a lot about how we think and only a little, if anything, about what’s going on with the social lives of invertebrates.

As you watch the clip below, notice that they explain the behavior not descriptively, but metaphorically. Flatworm mating behavior is like war and wars have winners and losers:

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5fx-YgcP8Gg[/youtube]

So the narrator explains that flatworm “sex is more like war than love.” Worms are “swordsmen” who are “penis fencing.” (Mix metaphors much?) They carry “double daggers” (penises). And “the first one to make a successful jab, delivers its sperm.”

Notice how the narrator genders the hermaphroditic flatworms. Because they have penises they are “swordsmen.” Apparently their equally functional capacity to be inseminated is eclipsed by their dangerous daggers!

And notice, too, how they describe the flatworm who becomes inseminated as the “loser.” The “losing flatworm,” the narrator explains, “bears the burden of motherhood, committing valuable resources to having offspring.”

Wow.

Sperm on the “loser”:

Now it may be true that being the “mother” involves the use of resources. [Note: And this is a nod to the evolutionary logic involved.] But even so, we would never call the females of non-hermaphroditic sexual species “losers” would we? I mean, they both get to pass on their genetic material, and doesn’t that make them both winners from an evolutionary perspective?

No doubt it seems reasonable to call the functional female of the pair a loser in a sexist world in which childbearing is defined as a disability (according to the Americans with Disabilities Act) and childraising is defined as non-productive (it garners no wages or benefits and cannot be put on a resume). Gosh, being non-hermaphroditic, human females are losers by default. They don’t even get to play the game.

So sexism is one way to explain the wildly offensive characterization of the inseminated flatworm as a “loser.” But it also may just be that, in choosing a war/sports metaphor to describe flatworm behavior, they inevitably had to characterize one or the other as a loser. This is a great example of the folly of metaphor. Metaphors can be used to make something unfamiliar make sense by comparing it to something familiar, but it also runs the risk of forcing the thing being explained to mirror the thing you use to explain it with.

It’s simply sloppy. And, all too often, it results in projecting ugly realities with which we are all too familiar onto those things we don’t really understand.

For another example of the projection of socially constructed human relations onto the body, see our post on sperm, eggs, and fertilization.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Women’s and men’s washrooms: we encounter them nearly every time we venture into public space. To many people the separation of the two, and the signs used to distinguish them, may seem innocuous and necessary. Trans people know that this is not the case, and that public battles have been waged over who is allowed to use which washroom. The segregation of public washrooms is one of the most basic ways that the male-female binary is upheld and reinforced.

As such, washroom signs are very telling of the way societies construct gender. They identify the male as the universal and the female as the variation. They express expectations of gender performance. And they conflate gender with sex.

I present here for your perusal, a typology and analysis of various washroom signs.

[Editor: After the jump because there are dozens of them… which is why Marissa’s post is so awesome…]

The phrase “nature/nurture debate” refers to an old competition between those who think that human behavior and psychology is determined by biology (that is, genetics, both evolutionary and individual, hormones, neurology, etc) and those who believe that it is determined by environment (that is, socialization, cultural context, experiences in childhood, etc). While the nature/nurture debate rages in the mass media, most scholars reject it altogether. Instead, social scientists and biologists alike recognize that our behavior and psychology is the result of an interaction between nature and nurture (yep, even sociologists like myself).

A recent story on NPR illustrates this beautifully. James Fallon, a neuroscientist specializing in sociopaths, had been scanning the brains of murderers for 20 years. His research had demonstrated that sociopath brains have a distinct appearance: dark patches in the orbital cortex, the part of the brain responsible for moral thinking and controlling impulses.

You can see the dark patches in the brain on the right, the brain on the left is a “normal” brain:

At a family gathering one day, Fallon’s mom mentions that there were some pretty violent types in Fallon’s own family history (it apparently didn’t come up anytime in the previous 20 years !!!) and, so, he investigates. It turns out that there were eight proven and alleged murders in his ancestral line, including Lizzy Borden, one of the most famous murderers in history. Because Fallon knows that the atypical neurology associated with sociopaths runs in families, he decided to scan the brains of all his family members. No one had the dark patches.

Except him. Fallon had the dark patches. In fact, that brain on the right: that’s him.

Not only did he have the neurology of a typical sociopath, he also carried a genetic determinant known to be associated with extreme violence.

Fallon doesn’t have the answer to why he’s not a sociopath, but scientists think that a person needs to have some sort of experiential trigger, like abuse as a child, in addition to a biological predisposition.

Significantly, [Fallon] says this journey through his brain has changed the way he thinks about nature and nurture. He once believed that genes and brain function could determine everything about us. But now he thinks his childhood [and his awesome mom] may have made all the difference.

For related examples, see our posts on the response of testosterone levels to political victories and the historical shift in the average age of menstruation.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

A blog post at Gallup, sent along by Michael Kimmel, discussed nearly 25 years of US opinion on the cause of homosexuality. The data shows a slow decline in the percent of people who think that people are “made” gay or lesbian by their upbringing or environment (the nurture argument) and a slow rise in the number of people who think they are “made” gay or lesbian by biology (the nature argument). The two meet in the late 1990s and, throughout the 2000s, they’ve been more-or-less neck-and-neck.

I welcome speculation as to why the trend didn’t continue such that nature ended up beating nurture good by 2010. I can’t think offhand of a reason why.

—————————

Lisa Wade is a professor of sociology at Occidental College. You can follow her on Twitter and Facebook.

The nature/nurture debate that posits a competition between biological and social/cultural influences on human behavior is alive and well in the mass media. But scholars largely agree that culture and biology interact; biological realities shape our social world, but our social world also shapes our biologies.

One strain of research demonstrating this has shown that men’s testosterone levels (associated with feelings of well-being) rise and drop in response to social (and socially constructed) cues. For example, the testosterone levels of the winner of a tennis match will rise after his win, while his opponent will see his levels go down. Similarly, measuring men’s testosterone levels won’t tell you which men walking down the sidewalk will enter a strip club, but the men leaving the strip club will have higher testosterone levels than the men who passed it by.

Matt C. alerted me to a test of this phenomenon using the Presidential election. There was a slight drop in testosterone levels for men who voted for Obama (normal because men’s testosterone levels tend to drop at night), but a dramatic drop for men who voted for McCain or the Libertarian candidate, Barr.

So, there you have it, biological responses to social cues.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Adeste S. sent in this performance by two women about the difficulties and frustrations of being transgendered:

Performed at Brave New Voices.

NEW! (Mar. ’10): Ryan sent in this video of Sass Rogando Sasot speaking to the United Nations about transgender rights. From an article at Coilhouse:

Her speech, titled “Reclaiming the Lucidity of Our Hearts”, addresses the need for vastly improved acceptance, support and protection of transgender citizens worldwide.

Her entire presentation is very moving, but about 8 minutes into this clip, something shifts in Sasot’s voice and delivery. What began as an engaging speech swiftly transforms into something far more urgent, immediate, and beautiful.

We posted earlier about the biology behind the controversy over Caster Semenya’s sex. Germán I. R.-E. and Philip Cohen (who has his own post on the topic) asked that we comment on her recent makeover.

Some sociologists argue that gender (as opposed to sex) is really more about performance than it is about our bodies. That is, we do gender and, when we do it in ways that other people recognize, everyone feels satisfied. This is, perhaps, what Caster Semenya’s handlers were hoping for when she submitted to a makeover for South Africa’s YOU Magazine:

Notice that Semenya carries the same body into this photoshoot, but she is properly adorned with make up, feminine clothing, jewelry, a passive pose, and a pleasant and inviting facial expression (because to be feminine is to be accommodating).

Perhaps more importantly, the copy and the interview tells the reader that Semenya likes dressing up and looking pretty, another important indicator of both femininity and non-masculinity. The cover says:

WE TURN SA’S POWER GIRL INTO A GLAMOUR GIRL – AND SHE LOVES IT!

(Notice, too, the implication that power and glamour are opposed.)

This insistence that Semenya feels (or wants to feel) feminine, as well as looks it, is mirrored in the text (as summarized by the Guardian):

It carries an interview with the 18-year-old student. “I’d like to dress up more often and wear dresses but I never get the chance,” she says. “I’d also like to learn to do my own makeup.”

The lifestyle magazine quotes Semenya’s university friends saying that she wants to buy stilettos and have a manicure and pedicure. Semenya adds: “I’ve never bought my own clothes – my mum buys them for me. But now that I know what I can look like, I’d like to dress like this more often.”

You magazine says that, after the photoshoot, Semenya told her manager that she would like to buy all the outfits she had modelled.

So, in the face of the leaked and unconfirmed finding that Semenya has undescended testicles and higher levels of testosterone than the “average” woman (see note at end*), there is an assertion here that what matters (i.e., the measure of sex that we should attend to) is her gender identity (feeling feminine) and her gender performance (doing femininity).

Anna N. at Jezebel points to how the public interest in Semenya’s sex may have pressured her, and those around her, to play this gender game. She writes:

…up until now, Semenya and her family have been unapologetic about the way she looks and dresses. Her father said that she had always preferred pants, but that she was still a woman — and the idea that she has to put on a dress and lipstick to prove her femaleness to people is pretty depressing.

It is also something that almost all women in Western countries do everyday. We perform gender, in part out of habit and in part consciously, all the time. Semenya hasn’t cared about this performance and that is at least in part why the controversy over her sex is taking the form that it is.

* Note: The release of male-related hormones, androgens, isn’t the whole story here. Cells must also have the relevant receptors for the presence of the hormones to matter. Semenya likely is lacking some of those receptors, either in her whole body on in parts of her body, because her body obviously didn’t respond to the hormones (otherwise she would have a penis and scrotum). My point here is dual: (1) the presence of testicles and testosterone doesn’t tell the whole story and (2) even if we knew the whole story, it doesn’t tell us if she is female or male. What if her body doesn’t detect the presence of those androgens? What if it reads the presence of some of them, but not others? What if she is chimera or mosaic? All these are interesting questions biologically, but the answers will not tell us whether she is male or female because sex, like gender, is a social construction.

—————————

Lisa Wade is a professor of sociology at Occidental College. You can follow her on Twitter and Facebook.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

I saw this footage of flatworm reproduction years ago on PBS and I was so excited when Robin H. sent it in!

Flatworms are hermaphroditic. All flatworms can inseminate and be inseminated. These flatworms also have two penises each. Flatworms are sexual. That is, they reproduce sexually by finding a partner with which to trade genetic material. (Asexual creatures do not trade genetic material, they reproduce by making copies of themselves.)

A flatworm reveals its two penises (in white):

What is interesting about this clip sociologically (in case you’re not already intrigued enough) is how the narrator describes what the flatworms are doing.

Let’s first suppose that it makes little sense to attribute human emotions and motivations to flatworms. Let’s also suppose that narrations of animal behavior are often going to tell us a lot about how we think and only a little, if anything, about what’s going on with the social lives of invertebrates.

As you watch the clip below, notice that they explain the behavior not descriptively, but metaphorically. Flatworm mating behavior is like war and wars have winners and losers:

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5fx-YgcP8Gg[/youtube]

So the narrator explains that flatworm “sex is more like war than love.” Worms are “swordsmen” who are “penis fencing.” (Mix metaphors much?) They carry “double daggers” (penises). And “the first one to make a successful jab, delivers its sperm.”

Notice how the narrator genders the hermaphroditic flatworms. Because they have penises they are “swordsmen.” Apparently their equally functional capacity to be inseminated is eclipsed by their dangerous daggers!

And notice, too, how they describe the flatworm who becomes inseminated as the “loser.” The “losing flatworm,” the narrator explains, “bears the burden of motherhood, committing valuable resources to having offspring.”

Wow.

Sperm on the “loser”:

Now it may be true that being the “mother” involves the use of resources. [Note: And this is a nod to the evolutionary logic involved.] But even so, we would never call the females of non-hermaphroditic sexual species “losers” would we? I mean, they both get to pass on their genetic material, and doesn’t that make them both winners from an evolutionary perspective?

No doubt it seems reasonable to call the functional female of the pair a loser in a sexist world in which childbearing is defined as a disability (according to the Americans with Disabilities Act) and childraising is defined as non-productive (it garners no wages or benefits and cannot be put on a resume). Gosh, being non-hermaphroditic, human females are losers by default. They don’t even get to play the game.

So sexism is one way to explain the wildly offensive characterization of the inseminated flatworm as a “loser.” But it also may just be that, in choosing a war/sports metaphor to describe flatworm behavior, they inevitably had to characterize one or the other as a loser. This is a great example of the folly of metaphor. Metaphors can be used to make something unfamiliar make sense by comparing it to something familiar, but it also runs the risk of forcing the thing being explained to mirror the thing you use to explain it with.

It’s simply sloppy. And, all too often, it results in projecting ugly realities with which we are all too familiar onto those things we don’t really understand.

For another example of the projection of socially constructed human relations onto the body, see our post on sperm, eggs, and fertilization.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.