Cross-posted at Family Unequal.

As I wrote about the older-birth-mothers issue recently (first, and then), I didn’t comment on the photo illustrations people are using with the stories. But when an alert reader sent this one to me, from Katie Roiphe’s post in Slate, I couldn’t help it:

Something about that picture and “women in their late 30s or 40s” rubbed my correspondent the wrong way, or rather, led her to write, “Late 30s or early 40s?!?”

Since this was from a legit website that credits its stock agency, I was able to visit Thinkstock and search for the photo. Sure enough:

Of course, it’s not news, so the title “Middle-aged woman holding her newborn grandson” doesn’t make it a less true illustration of the older-mother phenomenon than one captioned “Desperate aging woman clings to feminist myth that it’s OK to delay childbearing.” But it gives you an idea of what the Slate editor was looking for in the stock photo.

I looked around a little, and found one other funny one. Another Slate essay,this one by Allison Benedikt, was reprinted in Canada’s National Post, and they laid it out like this:

When I visited the Getty Images site, I discovered this picture was taken in China. Here’s how it’s presented:

This one, which is a picture of real people, looks like it could be a grandmother, or maybe more likely a caretaker. Regardless, it’s sold as an illustration of a story about China’s elderly having too few grandchildren to take care of them, which is vaguely related to the content of the story, but that’s not what the Post’s caption points to:

It’s true that older parents are more established and experienced but many of those experiences are, from a genetic point of view, negative, says Allison Benedikt.

Anyway, there were others where the women looked pretty old for the story, but I couldn’t find them in the catalogs, so I stopped.

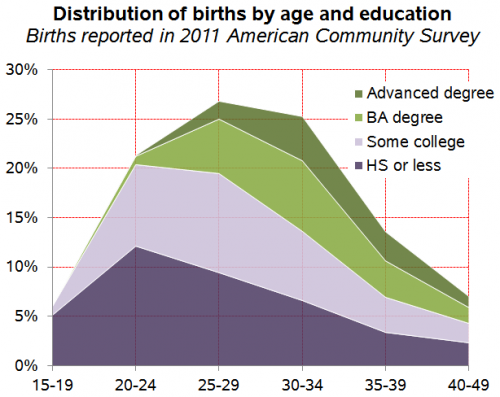

This is all relevant to one of my critiques of these stories, which is that they make it seem like having children at older ages has become more common than it was in the past. That’s true compared with 1980, but not 1960. The difference is it’s more likely to be their first child nowadays. So Benedikt is way off when she writes,

Remember how there was that one kid in your high school class whose parents were sooooo old that it was weird and creepy? That’s all of us now. Oops.

As I showed, 40-year-old women are less likely to have children now than they were when she was a kid. And when Roiphe writes of the “50-year-old mother in the kindergarten class [who] attracts a certain amount of catty interest and disapproval,” she should be aware that the disapproval — which I don’t doubt exists — is not about the increased frequency of older mothers, but about how people think about them.

Philip N. Cohen is a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland, College Park, and writes the blog Family Inequality. You can follow him on Twitter or Facebook.