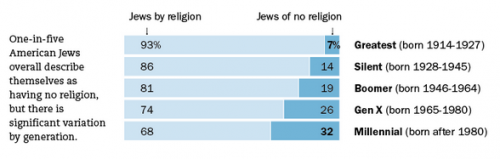

The Pew Research Center has released the data from new survey of religious and non-religious Jews. They find that almost a quarter of Jews (22%) describe themselves as being “atheist,” “agnostic,” or “nothing in particular.” The percentage of Jews of no religion correlates with age, such that younger generations are much more likely to be unaffiliated. Nearly a third of Millennials with Jewish ancestry say they have no religion (32%), compared to 19% of Boomers and 7% of the Greatest Generation.

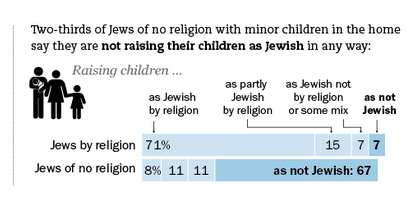

A majority of Jews with no religion marry non-Jews (79%); 67% have decided against raising their children with the religion.

As a result of intermarriage, the percent of all Jews who have only one Jewish parent is rising. While 92% of people born between 1914 and 1927 had two Jewish parents, Millennials are as likely as not to have just had one.

As a result of intermarriage, the percent of all Jews who have only one Jewish parent is rising. While 92% of people born between 1914 and 1927 had two Jewish parents, Millennials are as likely as not to have just had one.

Cross-posted at Pacific Standard.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.