A recent Pew survey compared attitudes a year ago and last month on the subject of abortion. The 2015 survey was done in the immediate wake of those now-famous videos of Planned Parenthood officials, videos shot surreptitiously and edited tendentiously. The demographic that showed the largest swing in opinion was Conservative Republicans.

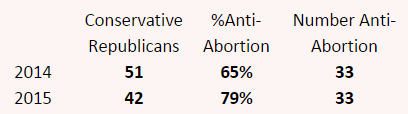

Among people who identified themselves as Conservative Republicans, opposition to abortion rose from 65 to 79%. Four out of five Conservative Republicans now oppose abortion. No other group in the survey comes in at more than half.

The obvious explanation is that in the past year an additional 14% of Conservative Republicans have become more conservative on abortion. The hardliners are becoming even harder. But there’s another possibility – that many of the Conservative Republicans who did not oppose abortion a year ago no longer call themselves Conservative Republicans.That’s not as unlikely as it might seem.

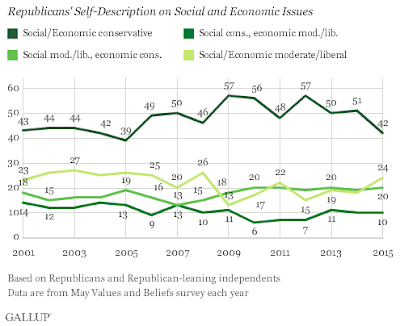

The Gallup poll shows that among Republicans, those who identified themselves as conservative on both economic and social issues – the largest segment of the faithful – dropped from 51 to 42%. What if all the dropouts were abortion moderates?

I did some simple math. I imagined 100 Republicans in 2014. Of those, 51 were self-identified conservatives and of those 65% opposed abortion. That makes 33 who thought abortion should be illegal nearly all the time.

Last month, only 42 of those 100 Republicans said they were thoroughly conservative, 9 fewer than a year ago. Of those left, 79% were anti-abortion. That makes 33. In my scenario, these were the same 33 as a year ago. The 9 who defected to the less-than-fully-conservative camps were the ones who were wishy-washy about making abortion totally illegal. These nine people looked at the hardcore, and the next time that a pollster asked them about where they stood politically, they thought, “If being a Conservative Republican means wanting all abortions to be illegal, maybe I’m not so conservative after all.”

I’m speculating here of course — the data and calculations here are surely too simplistic; I am not a political scientist — but maybe the party purists are indeed forcing others who used to be close to them politically to rethink their identification as Conservative Republicans.

Originally posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.