For years now, expecting parents have been popping balloons and cutting colorful cakes to announce the sex of their babies. These “gender reveal parties” can be a fun new take on the baby shower, but they also show just how much we invest in the gender identities of children. In a world where gender inequality persists and gender identities can be in flux, cultural traditions like this can lock people into rigid thinking that separates boys and girls.

Of course, point this out at the wrong time and you’ll usually get accused of raining on the parade. It’s just a cake after all, right? The tricky part is that social scientists often show how identities can turn into ideologies that have real stakes for human behavior.

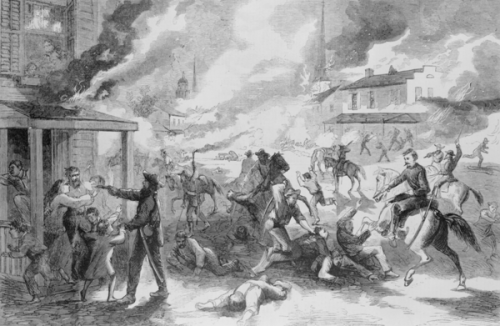

For a dramatic example, last week the world got footage of the gender reveal party that sparked a massive 2017 wildfire in Arizona. These parents wanted to go big to announce their new baby boy—so big that it warranted explosions in the middle of dry grasslands.

It’s not that gender stereotyping directly caused this fire—even if we didn’t have a rigid gender binary, people would still start disasters with a stray campfire or sparkler. This case is still useful for thinking about gender, though, because what we celebrate and how we celebrate it shows a lot about where people learn to place their interest and effort. We don’t have massive parties for baby’s first steps or first conversation, and I can’t think of a time when a First Communion needed 800 fire fighters to come clean up afterwards.

Evan Stewart is an assistant professor of sociology at University of Massachusetts Boston. You can follow his work at his website, on Twitter, or on BlueSky.