Cross-posted at Family Inequality.

Sociologist, segregate thyself? A little inside-sociology post.

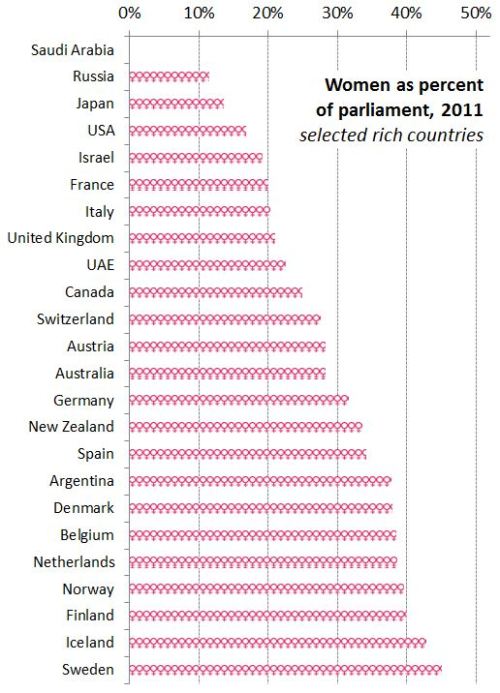

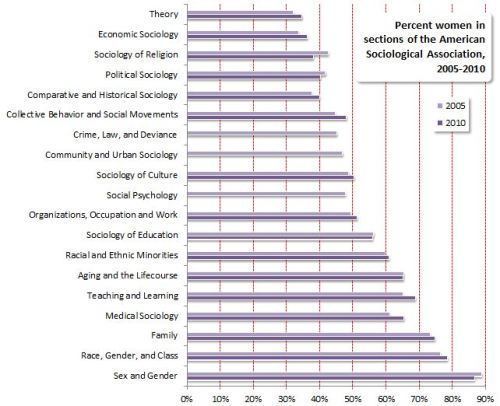

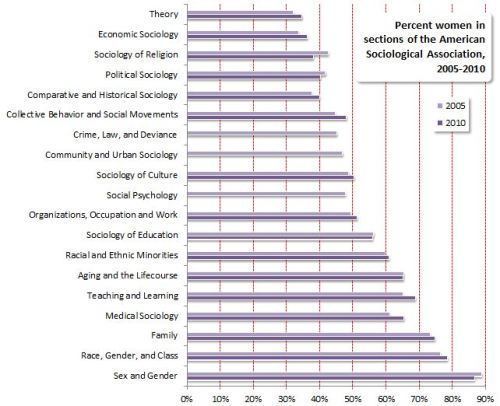

A report from the research folks at the American Sociological Association (ASA) got me thinking about gender-segregated sociology. I added a few numbers from other sources to provide a quick look at three moments of gender segregation within the discipline.

People may (or may not) want to be sociologists, they may or may not be accepted to graduate schools, thrive there (with good mentoring or bad), freely choose specializations, complete PhDs, publish, get jobs, and so on. As in most workplaces, gender segregation represents the cumulative intentions and actions of people in different institutional settings and social locations.

#1: Phds

Since the mid-1990s, according to data from the National Science Foundation, women have outnumbered men as new sociology PhDs, and a few years ago we approached two-thirds female. In the three years to 2009, however, the number of PhDs has dropped by a third, and women have accounted for two-thirds of that drop. I have no idea what’s going on with that.

For the time being, then, we’re close to 50/50 in gender balance for producing PhDs. But academic careers can be long, so all those years in the 1970s and 1980s when men outnumbered women by so much still affect today’s discipline. Among members of the ASA today, women are 7 years younger than men, on average. Which means the men are in higher positions, on average, as well.

For the time being, then, we’re close to 50/50 in gender balance for producing PhDs. But academic careers can be long, so all those years in the 1970s and 1980s when men outnumbered women by so much still affect today’s discipline. Among members of the ASA today, women are 7 years younger than men, on average. Which means the men are in higher positions, on average, as well.

#2: Specialization

Choosing what area of sociology to study is a combination of personal interest and ambition, institutional setting and mentoring, and happenstance of various kinds. (This is separate from the question of how narrowly to specialize in one’s specialization, which has a big impact on the quantity of publication, since switching topics is risky and costs valuable time.) So it wouldn’t be accurate to describe this as simply a free choice. But, once someone is a member of the ASA, which is open to anyone, then the choice of identifying with a certain area of research is free (or, actually, costs a few dollars a year), through joining sections of the association.

The pattern of section belonging shows a striking level of gender segregation. On a scale of 1 to 100, I calculate the sections are segregated at a level of .28. (That is the same level of segregation I calculated in the gender distribution between major fields for PhDs, such as engineering and social sciences.) Put another way, the correlation between the percentage of women and percentage of men across the sections is a strong -.64. And by both measures the segregation has increased since 2005.

Joining a section means voting to increase the number of presentations in that area at the national conference, getting a newsletter, maybe an email list, being invited to a reception, and having the chance to serve on committees and run for office arranging all those things. At its best it’s a community of scholars interested in similar subjects. Anyway, the point is it’s not a restrictive club or job competition.

Joining a section means voting to increase the number of presentations in that area at the national conference, getting a newsletter, maybe an email list, being invited to a reception, and having the chance to serve on committees and run for office arranging all those things. At its best it’s a community of scholars interested in similar subjects. Anyway, the point is it’s not a restrictive club or job competition.

#3: Editorial boards

Finally, prestigious academic journals have one or more editors, often some associate editors, and then an editorial board. In sociology, this is mostly the people who are called upon to review articles more often. Because journal publication is a key hurdle for jobs and promotions, these sociologists serve as gatekeepers for the discipline. In return they get some prestige, the occasional reception, and they might be on the way to being an editor themselves someday. I didn’t do a systematic review here, but I looked at the two leading research journals — American Sociological Review and American Journal of Sociology, as well as two prestigious specialized journals — Sociological Methods and Research, and Gender and Society (which is run by its own association, Sociologists for Women in Society, whose membership includes both women and men).

(I included the editors, book review editor, consulting or associate editors, and editorial board members, but not managing editors. The number included ranged from 33 to 73.)

(I included the editors, book review editor, consulting or associate editors, and editorial board members, but not managing editors. The number included ranged from 33 to 73.)

I’m not attributing motives, describing gender discrimination, or even making a judgment on all this. There are complicated reasons for each of these outcomes, and without more research I couldn’t say nature/nurture, structure/agency, system/lifeworld, etc.

But gender segregation never happens for no reason.

Update: Kim Weeden pointed me toward the complete list of section memberships by gender for 2010. So here is a a graph of the gender compositions expanded to include all 49 sections. Also, with that expanded data, I recalculated the segregation level, and it’s .25.

True, the women’s deodorant mentions it’s “gentle on sensitive skin” (which is what you get when you shave your armpits, I guess). But that’s much less noticeable than the color difference. And, what’s the difference between “unscented” and “fragrance free”?

True, the women’s deodorant mentions it’s “gentle on sensitive skin” (which is what you get when you shave your armpits, I guess). But that’s much less noticeable than the color difference. And, what’s the difference between “unscented” and “fragrance free”?