Children are our most important resource. Everyone says it, but we don’t really mean it.

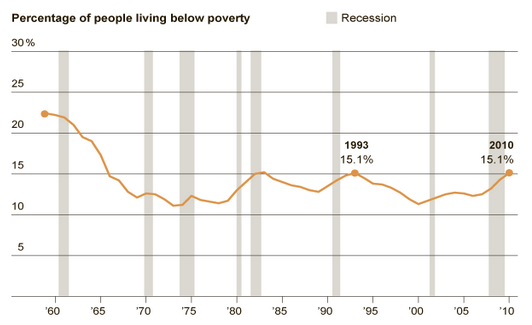

Exhibit one: the percentage of children under the age of 18 that live in poverty. In 2007, at the peak of our previous economic expansion, the child poverty rate was 18%. In 2009, it hit 20%. The figure below provides a look at child poverty rates in each state. New Hampshire had the lowest rate: 11%. Mississippi the highest rate: 31%. According to a recently released Census Bureau study, the 2010 national child poverty rate was 22%.

How Do We Measure Poverty?

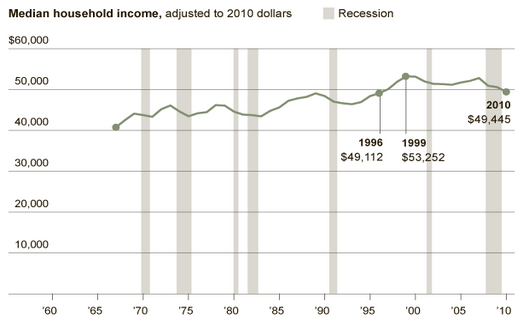

Children under the age of 18 are counted as poor if they live in families with income below U.S. poverty thresholds. There are a range of poverty thresholds which are based on family size and number of children. These poverty thresholds are far from generous. The 2009 poverty threshold for a family of two adults and two children was$21,756.

Sadly our poverty rates understate the seriousness of our poverty problem, for children and adults. The history of how we developed and calculate our official poverty thresholds provides perhaps the clearest proof of the inadequacy of current statistics. First introduced in 1965, the thresholds were based on previous work by the Department of Agriculture (DOA). The DOA created an “economy” food plan in the 1950s that was designed for “temporary or emergency use when funds are low.” DOA surveys had also established that families of three or more persons spent approximately one-third of their after tax income on food. Our initial thresholds were set by multiplying the cost of the economy food plan (adjusted for family size) by three.

From 1966 to 1969, these poverty thresholds were revised annually by the yearly change in the cost of the items contained in the economy food plan. After 1969, and still today, the poverty thresholds were adjusted by the rise in the consumer price index.

Our poverty rates are calculated by comparing pre-tax family incomes to these thresholds.

Why the Poverty Threshold is Deficient

This methodology has produced a poverty standard and estimates of poverty that are deficient for several important reasons:

First, our knowledge of nutrition has significantly changed since the 1950s.

Second, families now spend approximately one-fifth of their after-tax income on food, not one-third. That correction alone would mean that the food budget should be multiplied by 5 rather than 3, thereby producing higher thresholds and poverty rates.

Third, poverty is best thought of as a relative condition, which means that it should not be measured by comparing incomes to an unchanging standard based on the cost of a 1950’s economy food plan.

Fourth, poverty rates should be calculated using after-tax family income adjusted to include the value of government support programs like food stamps (which are also fluctuating and often cut in hard times), not unadjusted pre-tax family income.

A Better Measure

Researchers, drawing on the work of the National Academy of Sciences Panel on Poverty and Family Assistance Economists, have developed an alternative experimental approach to measuring poverty. They start with a reference family, two adults and two children. Then, using Consumer Expenditure Surveys, they calculate the dollar amount of spending on food, clothing, shelter, utilities and medical care by all reference families in a given year.

The poverty threshold for the reference family is set at the midpoint between the 30th and 35th percentile of the spending distribution for all families with two adults and two children. Small multipliers are then used to add spending estimates for other needs, such as transportation and personal care, slightly raising the poverty threshold. This threshold is adjusted for families of other compositions.

The chart below shows national poverty rates for the years 1996 to 2005. We see that the rates produced by this experimental methodology are significantly higher than the official rates.

Strikingly, while the official poverty rate is lower in 2005 than in 1996, the 2005 experimental poverty rate is the highest in the period. The difference is largely explained by the fact that the experimental measure incorporates changes in the availability of social programs and the relative importance of non-food goods and services in family spending.

Returning to the issue of child poverty, the table below highlights the difference between the two measures for specific demographic groups. Notice that the child poverty rate calculated using the experimental measure is always higher than the official rate. As previously stated, the official 2010 child poverty rate is 22 percent. The experimental rate would no doubt be several percentage points higher, closing in on 25 percent.

What can one say about a situation where between one-fifth and one-fourth of all children in the United States live in poverty? Language like “outrageous,” “unacceptable,” and “indicator of a flawed economic system” comes to mind. What also comes to mind is the fact that these poverty statistics rarely get the attention they deserve, as does the question of why that is so.