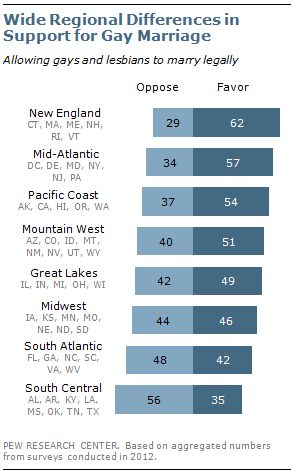

For the last week of December, we’re re-posting some of our favorite posts from 2012.

Today, most people in the U.S. see childhood as a stage distinct from adulthood, and even from adolescence. We think children are more vulnerable and innocent than adults and should be protected from many of the burdens and responsibilities that adult life requires. But as Sidney Mintz explains in Huck’s Raft: A History of American Childhood, “…childhood is not an unchanging biological stage of life but is, rather, a social and cultural construct…Nor is childhood an uncontested concept” (p. viii). Indeed,

We cling to a fantasy that once upon a time childhood and youth were years of carefree adventure…The notion of a long childhood, devoted to education and free from adult responsibilities, is a very recent invention, and one that became a reality for a majority of children only after World War II. (p. 2)

Our ideas about what is appropriate for children to do has changed radically over time, often as a result of political and cultural battles between groups with different ideas about the best way to treat children. Most of us would be shocked by the level of adult responsibilities children were routinely expected to shoulder a century ago.

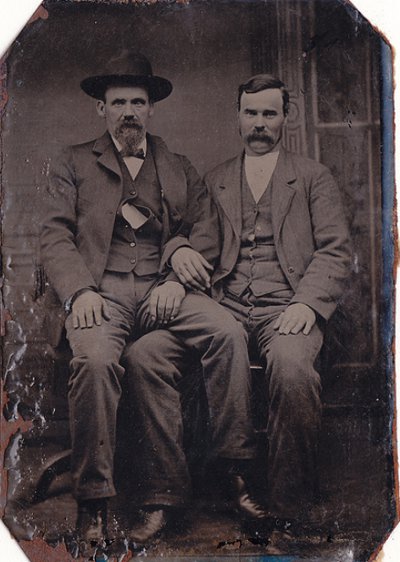

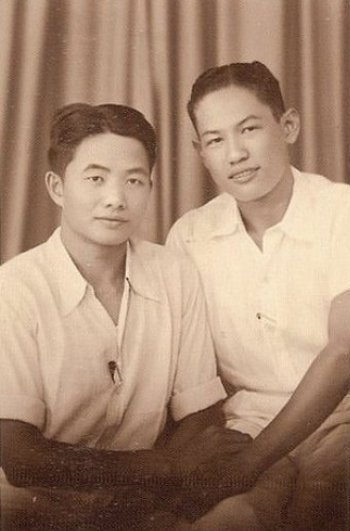

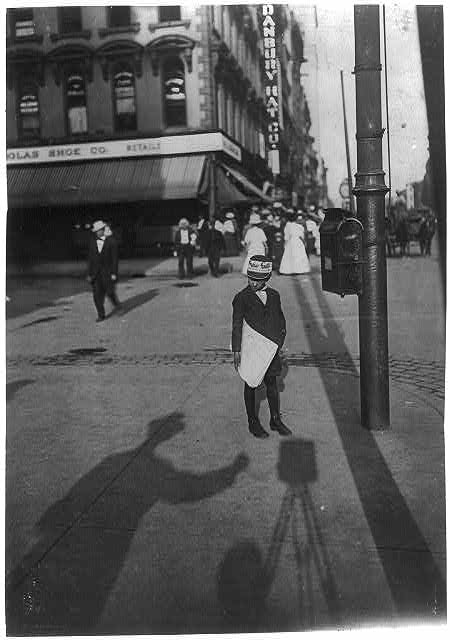

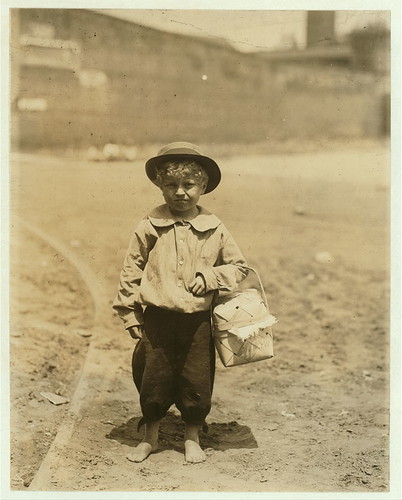

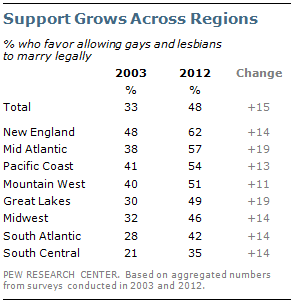

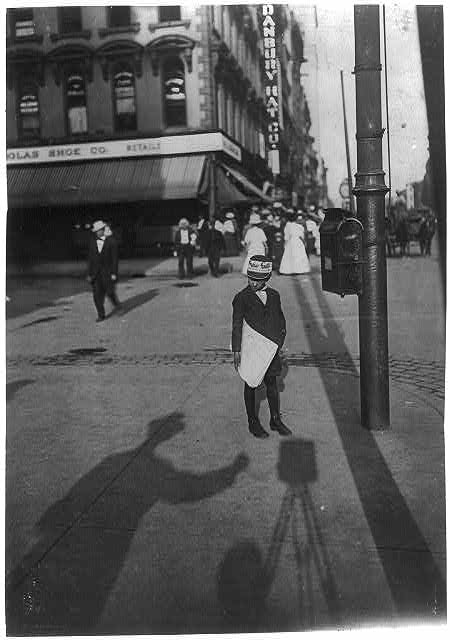

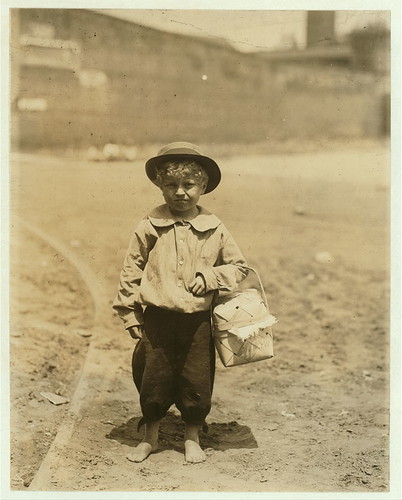

Reader RunTraveler let us know that the Library of Congress has posted a collection of photos by Lewis Hine, all depicting child labor in the early 1900s in the U.S. The photos are a great illustration of our changing ideas about childhood, showing the range of jobs, many requiring very long hours in often dangerous or extremely unpleasant conditions, that children did. I picked out a few (with some of Hine’s comments on each one below each photo), but I suggest looking through the full Flikr set or the full collection of over 5,000 photos of child laborers from the National Child Labor Committee:

“John Howell, an Indianapolis newsboy, makes $.75 some days. Begins at 6 a.m., Sundays.” 1908. Source.

“Interior of tobacco shed, Hawthorn Farm. Girls in foreground are 8, 9, and 10 years old. The 10 yr. old makes 50 cents a day.” 1917. Source.

“Interior of tobacco shed, Hawthorn Farm. Girls in foreground are 8, 9, and 10 years old. The 10 yr. old makes 50 cents a day.” 1917. Source.

“Eagle and Phoenix Mill. ‘Dinner-toters’ waiting for the gate to open.” 1913. Source.

“Eagle and Phoenix Mill. ‘Dinner-toters’ waiting for the gate to open.” 1913. Source.

“Vance, a Trapper Boy, 15 years old. Has trapped for several years in a West Va. Coal mine. $.75 a day for 10 hours work. All he does is to open and shut this door: most of the time he sits here idle, waiting for the cars to come. On account of the intense darkness in the mine, the hieroglyphics on the door were not visible until plate was developed.” 1908. Source.

“Vance, a Trapper Boy, 15 years old. Has trapped for several years in a West Va. Coal mine. $.75 a day for 10 hours work. All he does is to open and shut this door: most of the time he sits here idle, waiting for the cars to come. On account of the intense darkness in the mine, the hieroglyphics on the door were not visible until plate was developed.” 1908. Source.

“Rose Biodo…10 years old. Working 3 summers. Minds baby and carries berries, two pecks at a time. Whites Bog, Brown Mills, N.J. This is the fourth week of school and the people here expect to remain two weeks more.” 1910. Source.

“Rose Biodo…10 years old. Working 3 summers. Minds baby and carries berries, two pecks at a time. Whites Bog, Brown Mills, N.J. This is the fourth week of school and the people here expect to remain two weeks more.” 1910. Source.

Hine’s photos make it clear how common child labor was, but their very existence also documents the cultural battle over the meaning of childhood taking place in the 1900s. Hine worked for the National Child Labor Committee, and his photos and especially his accompanying commentary express concern that children were doing work that was dangerous, difficult, poorly-paid, and that interfered with their school attendance.

In fact, the NCLC’s efforts contributed to the passage of the Keating-Owen Child Labor Act in 1916, the first law to regulate the use of child workers (limiting hours and forbidding interstate commerce in items produced by children under various ages, depending on the product). The law was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1918. This resulted in an extended battle between supporters and opponents of child labor laws, as another law was passed and then struck down by the courts, followed by successful efforts to stall any more legislation in the 1920s based on states-rights and anti-Communist arguments. Only in 1938, with the passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act as part of the New Deal, did child workers receive specific protections.

Even then, we had loopholes. While children working in factories or mines was redefined as inappropriate and even exploitative and cruel, a child babysitting or delivering newspapers for money was often interpreted as character-building. Today, the cultural battle over the use of children as workers continues. This year, the Labor Department retracted suggested changes that would restrict the type of farmwork children could be hired to do after it received significant push-back from farmers and legislators afraid it would apply to kids working on their own family’s farms.

As Mintz said, childhood is a contested concept, and the struggle to decide what kind of work, if any, is appropriate for any child to do continues.

For more examples, see Lisa’s 2009 post about child labor.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.